Data collection related to this article: “At the roots of a global environmental history: Ethiopian archives of nature.” https://zenodo.org/communities/ethiopian-archives-of-nature/

15 documents (10 datas). Includes in particular 10 documents (facsimiles and transcripts) from the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority (EWCA) library, with the kind permission of the managers, as part of the partnership established since 2019 between the EWCA, the French Centre for Ethiopian Studies (CFEE, UAR3137/ IFRE 23) and Tempora (UR 7468) at Rennes University 2.

The entire documentary collection of the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority is kept at the EWCA library in Addis Ababa: Yobek building (ዮቤክ ህንጻ), Tesema Aba Kemaw Street, Ambassador, Sengatera, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Tel.: +251 11 54 6808.

Coordinates: 9°00’49.3”N 38°44’51.7”E [geo:9.01352,38.74728].

Any research question is “armed,” as beautifully expressed by Antoine Prost (1996). The historian explained that it is always backed by “some idea of possible documentary sources and research procedures.” He thus stated a basic and yet crucial truth: “You must already be a historian to be able to ask a historical question” (ibid., 80). Yet, when I arrived in Ethiopia in 2009 to carry out an initial survey for my PhD, I—like many other doctoral students I encountered there—had no idea of the sources I needed for my research. I aimed to trace the history of the Simien National Park, created in 1969 in the north of the Ethiopian highlands and classified as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1978. The way I envisioned my fieldwork was then entirely led by historiography: I relied on academic literature and on the interpretation grid that I built up from it in a relevant way (according to the young researcher I was in 2009) which was, in fact, a very naive way (according to the less young researcher I am today).

During the first year of my PhD, which began in Quebec in 2008, I learned from North American, British, and Indian environmental histories that nature conservation always involved struggles: institutional struggle to control a territory; cultural struggle to promulgate a particular representation in the public space; material struggle to exploit a resource (Castonguay 2006, 7). My goal was thus to study the conflicts at play in setting up nature as a national park in the Ethiopian Mountains of Simien. My method would be to collect research materials shedding light on the history of the shaping of nature with this tripartite dimension: laws, regulations and activity reports would enable me to understand the institutional history of the park; tourist documentation and archives relating to tourist development would clarify its cultural history; and reports of surveys conducted by ecologists, botanists, and foresters would enable me to grasp the material evolution of ecologies in a national park. I followed this approach during my first weeks in Ethiopia, until I understood that such a generalist framework could not get near a historical reality which was, by definition, unique.

I first realized that, like other institutions of the centralized and centralizing nation-state, the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority (EWCA) had kept the entire documentation relating to the management of the country’s parks since their creation in the mid-1960s. Correspondence, job offers, minutes of meetings, budgets, orders for equipment: the EWCA had kept everything, but had neither catalogued nor filed anything. The more I collected and photographed the archives, the more I tried to classify them methodically: in one file, evidence of institutional history; in another, material relating more to culture; then, in a third file, archives of material history. However, I then realized that while this thematic division of history might be suitable to the way it would be transcribed, thematic partitioning of the materials left by this history would prevent it being traced back. One day I would learn from a law draft that the park inhabitants had been expelled in 1972, and that only 5,000 were still living there; the next day, I discovered in a tourist brochure about the fauna and flora that 12,000 people lived in the park in that same period. I would also learn from a mission report written by foresters that, in the mid-1980s, the Simien mountains were devastated by civil war; this information was immediately contradicted by a park warden’s notebook stating that in wartime, this region of scrubland was a real haven of peace for the populations. In most archives, authors presented nature and local populations as they wished them to be, so it was necessary to cross-reference their content: tracking down the institutional in cultural archives, searching the local history in international documentation, or locating the material in tourist propaganda.

Here, I will try to trace back this work in and about archives, based on three research projects that I carried out alone or with a team. The first project, carried out during my five years of PhD from 2008 to 2013, focused on an environmental history of the Ethiopian nation approached through the Simien National Park case. The second arose during several postdoctoral contracts. It materialized from 2018 to 2021 thanks to the French National Research Agency (ANR) which funded collective research on the global history of turning nature into heritage in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. Finally, this was followed by a third, parallel project which truly started in the autumn of 2021 as part of an application to the IUF (Institut universitaire de France). This final project returns to the starting point: Ethiopian national parks. But this research now aims at exploring global rather than national history. This Ethiopian loop in the archives of nature reveals the trajectories of Western professionals of African nature who participated in, and exposed, the history of a “postcolonial event”: the conversion of colonial administrators into international experts, and the encounters that connect them and oppose them to the leaders and inhabitants of independent Africa.

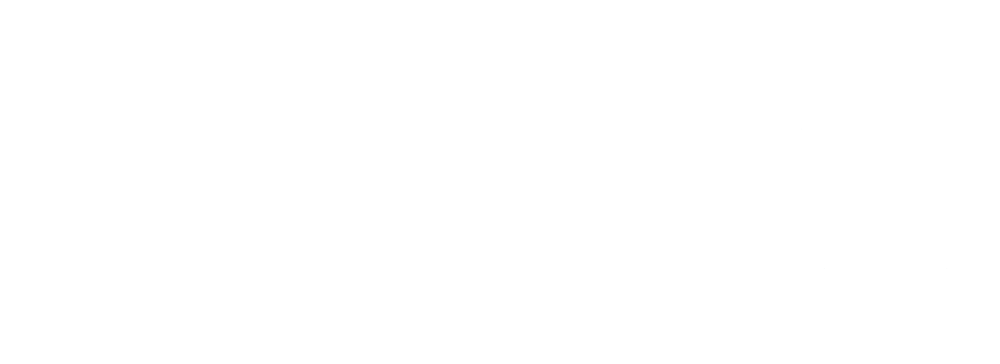

Map 1. Ethiopia and its first national parks (Awash, Omo, Simien)

Illustration by Marie Bridonneau and Guillaume Blanc.

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546567.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546568/files/Carte_1_Parcs.jpg.

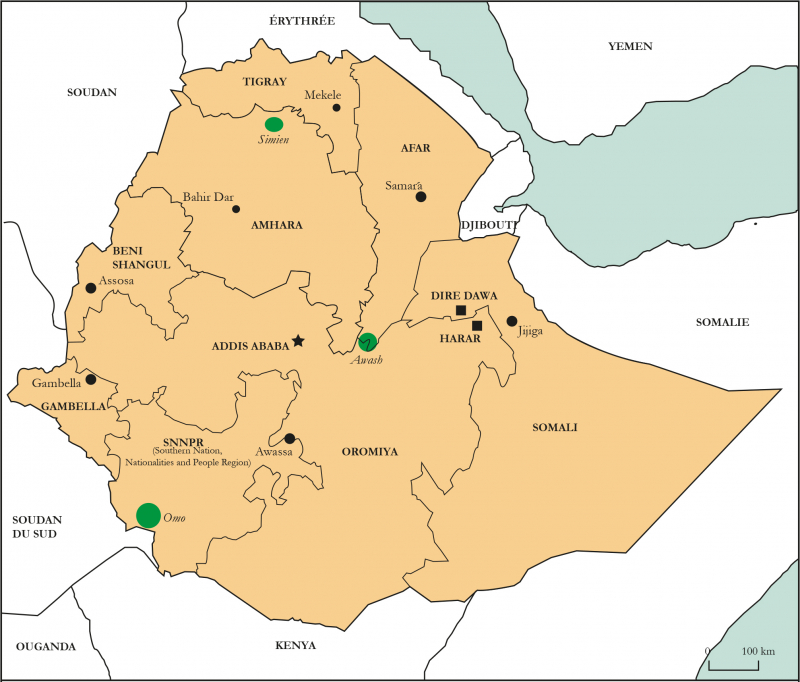

Map 2. The Simien Mountains National Park

Illustration by Amélie Chekroun and Guillaume Blanc.

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546567.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546568/files/Carte_2_Simien.jpg.

Boxed text. Socio-ecology of the Ethiopian Mountains of Simien

The daily life of Simien’s communities is similar to that found in the countryside elsewhere in the Ethiopia highlands. The inhabitants of the mountains subsist through agropastoralism by combining ploughing with oxen and extensive livestock breeding. Those who own more livestock than their neighbours can occasionally travel to the city to sell their farm products and buy other consumer goods (oil, soap, clothing). But, beyond these inequalities and the resulting power relationships, the community remains characterized by self-sufficiency and poverty. Livestock breeding is limited by demographic pressure, which reduces the size of herds and the amount of dung used as fertilizer. Agriculture is limited by land erosion caused by highly hydrophilic eucalyptus trees and aggravated by high domestic consumption of wood. To alleviate these issues, inhabitants optimize both their farming methods—by making terraces, practicing slash-and-burn agriculture, or alternating annual and perennial crops—and their housing methods, by the use of dried cow-pats or wheat straw. In doing so, they shape a resilient ecology where environmental constraints and modes of production are combined, and where the ability of human societies to adapt to the former are combined through the control of the latter.

The political framework of these socioecological structures also seems like that observed in the Highlands villages: the qäbälēa controls the distribution of land, seeds and fertilizers, and the villagers associate their leaders with the mängestb, to whom they swear individual and collective allegiance. However, Simien differs significantly from other parts of the Highlands countryside for at least two reasons. Nestled between 3,000 and 4,500 metres above sea level, Simien is primarily a scrubland region. Loosely controlled by the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia since the seventeenth century, Simien became truly part of the Ethiopian Empire since the first half of the twentieth century. Whether living at the extreme north of the Amhara region, which is well integrated to the Empire, or at the southernmost end of the Tigray, which has episodic irredentist claims, Simien inhabitants belong as much to those Amhara personifying the Ethiopian national identity as to those fringes challenging authority of the central government. Simien was then, for these reasons, set into a natural park. It was established as a national park by Haile Selassie in 1969, the Marxist government obtained its classification as UNESCO World Heritage in 1978, and since 1991, the federal authorities have been trying to limit the agropastoral exploitation of the area, following the criteria of good governance of nature defined by international conservation institutions. Source: Blanc (2016: 147–149).

a. “Neighbourhood” in Amharic, qäbälē in the countryside refers to a group of hamlets or a village. Created in 1974 to implement agricultural reform, the administrative unit is still named Farmers Association.

b. Mängeśt refers both to the “government,” the “state,” and whoever considered as being in power.

An environmental history of the Ethiopian nation

“In my opinion you must go to Bahir Dar.” I owe this advice to one of the staff at the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority (EWCA). This was in April 2009 on the7th floor of the Chaï na Buna building in the Mexico neighbourhood of Addis Ababa. This huge tower houses the administration managing Ethiopian import-export of tea [chaï] and [na] coffee [buna]. But it also houses the EWCA office over two floors. The Research Department, on the 7th floor, is where I asked for a “permit” to work on the Simien National Park history. The library, which holds much of the material produced by managers of the Ethiopian protected area, is on the 8th floor. However, I was not aware that this library existed, and neither did the employee who issued my permit. This is why, when I asked him where I could find the Simien Park archives, he suggested that I go 500 kilometres further north, to Bahir Dar, the capital of the Amhara National Regional State where the Parks Development and Protection Authority (PaDPA), the agency managing the region’s national parks, is located.

Three days later, in the nearby suburb of Bahir Dar, the PaDPA staff allowed me to photograph about twenty activity reports and development programs. But they only dated back to 2001. Since I wanted to go back to 1969 at least, the year of the official creation of the Simien Mountains National Park, the park managers directed me downtown, to the Department of Finance library. There, I was able to look at all the issues of Negarit Gazeta, the Ethiopian official newspaper published daily since 1944. I also looked at three files gathering the detailed minutes of a 1994 inter-ministerial conference organized to draw up the first inventory of the country’s protected areas. Then, when I returned to the PaDPA headquarters, I was advised to continue my research some 100 kilometres to the north, in the city of Gondar. There, the members of the Ethiopian Tourism Commission gave me access to tourist documentation dating back to the 1990s and 2000s, before advising me to go ever further north, to Debark, a small town at the foot of the Simien Mountains. At the national park entrance office there, I made three discoveries.

The park staff first told me that their offices and the archives kept there had been burned by the inhabitants in 1991, when the Marxist regime of the Derg [“committee” in Amharic], in power since 1974, fell. They then allowed me into a room where the logbooks kept by the park wardens, and the minutes they wrote for each offence in Simien, were stored. These documents, nearly 80,000 pages, had been packed in a cabinet without being filed since 1994, when the park offices were rebuilt. I tried to sort them as objectively as possible: since they were stacked on top of each other not by theme but by year, I photographed 1,000 sheets in a row, every 10,000 pages, from the bottom to the top of the cabinet, from 1994 to 2009. This material looked promising, but was nevertheless incomplete. This is why, after three weeks of photographing logbooks and minutes, I chose to go and visit the park. I came upon my third discovery at the end of a 220-kilometre loop in the Simien Mountains.

I was hoping to overcome the lack of existing documentation by resorting to what the historian Simon Schama calls the “archives of the feet.” The goal is to experiment with the site in order to detect, in the landscape of a so-called “natural” park, traces of intervention by the men and women who declared that this area was “natural” (Schama 1999, 32). This is what I attempted to do while hiking for twelve days, meeting Simien farmers and shepherds, observing the trails and campsites available to visitors, and interviewing tourist guides, cooks and wardens.

I completed this first trip round the Simien massif with one of the wardens. Malalegn drove me to the park office, where he asked me if I had found everything I needed for my studies. I told him about my research in Bahir Dar, Gondar, and Debark, and shared my disappointment at not finding the archives I was hoping to find when I left the capital two months ago. Malalegn then replied: “You’ll find all this in Addis, at the Chaï na Buna building library, it’s easy.” So I went back to the EWCA premises where I discovered the 8th floor and its library: the lack of a catalogue lengthened the documentary research, but I found the park regulations, activity reports prior to the 2000s, tourist documentation produced before the 1990s, correspondence between conservationist experts, and numerous reports of international scientific missions organized in the Simien Mountains since the 1960s.

This first survey was then completed by several research stays. Thanks to these sources, I was able to grasp the contemporary history of the Ethiopian nature and nation. When studied independently of each other, these sources are generally insignificant. A park creation act, a tourist brochure about fauna and flora, or a wildlife monitoring mission report tell us almost nothing about how nature is shaped. This is true for many very contemporary archives. The hundreds of reports and thousands of pages of institutional archives only “talk” when accumulated: a law can inform us about the state appropriation of space if we study the minutes that result from it; a tourist brochure can enlighten a national cultural policy if we analyze over time the formulaic style built up by an administration; the figures from a wildlife monitoring mission can inform whether claims of wildlife decline are true after examining, one by one, and decade by decade, the records for a given fauna species. These sources, shown here for illustration rather than analysis, say a lot, but to hear them, we must go beyond the “surprise – or torpor” caused by their excessive number and their “‘administrator-like’ discourse” (Rist 2002, 10).

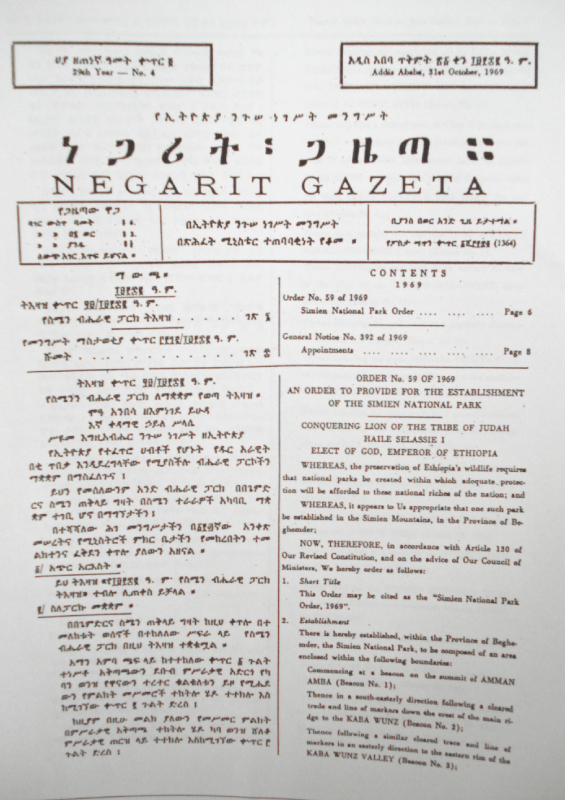

Document 1. The institutional shaping of nature

Imperial Ethiopian Government. 1969. “Order no.59. Simien National Park Order.” Negarit Gazeta 29–4, Addis Ababa, October 31st, 1969 (EWCA1). First page.

Permanent identifier (3 pages document): https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6545902.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6545903/files/Order-no.59-Simien-National-Park-Order-Negarit-Gazeta-29%E2%80%934.pdf.

Download transcript: https://zenodo.org/record/6545903/files/TRANSCRIPT-Order-no.59-Simien-National-Park-Order-Negarit-Gazeta-29%E2%80%934.odt.

Transcript

NEGARIT GAZETA

CONTENTS

1969

Order No. 59 of 1969

Simien National Park Order… Page 6

General Notice No. 392 of 1969

Appointments… Page 8

ORDER No. 59 OF 1969

AN ORDER TO PROVIDE FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SIMIEN NATIONAL PARK

CONQUERING LION OF THE TRIBE OF JUDAH HAILE SELASSIE I

ELECT OF GOD, EMPEROR OF ETHIOPIA

WHEREAS, the preservation of Ethiopia’s wildlife requires that national parks be created within which adequate protection will be afforded to these national riches of the nation; and

WHEREAS, it appears to Us appropriate that one such park be established in the Simien Mountains, in the Province of Beghemder;

NOW, THEREFORE, in accordance with Article 130 of Our Revised Constitution, and on the advice of Our Council of Ministers, We hereby order as follows:

1. Short Title

This Order may be cited as the “Simien National Park Order, 1969”.

2. Establishment

There is hereby established, within the Province of Beghemder, the Simien National Park, to be composed of an area enclosed within the following boundaries:

Commencing at a beacon on the summit of AMMAN AMBA (Beacon No. 1),

Thence in a south-easterly direction following a clear trade and line of markers down the area of the main ridge to the KABA WUNZ (Beacon No. 2);

Thence following a similar cleared trace and line of markers in an easterly direction to the eastern rim of the KABA WUNZ VALLEY (Beacon No. 3);

Thence following the eastern rim of the KABA WUNZ VALLEY in a north easterly direction to a point on the main SANKABER-AMBARAS track due southwestern corner of the GEECH ABYSS (Beacon No. 4);

Thence following a cleared trace and line of markers running in a northeasterly direction parallel to and at a distance of approximately 1500 meters from the DJINN BAHR RIVER to a point due south of the point where the main BEECH-SANKABER track crosses the said river (Beacon No. 5);

Thence in a straight line southeast to the main AMBA RAS-ARGEEN-CHENEK track (Beacon No. 6);

Thence following the said track in an easterly direction to the edge of the SIMIEN ESCARPMENT above DIHUARA (Beacon No. 7);

Thence following the said track in a northerly direction to DIHUARA VILLAGE (Beacon No. 8);

Thence following the main DIHUARA-TROATA-TEYA-DINNI track in a northwesterly direction to the northernmost foot of SARA AMBA (Beacon No. 9);

Thence following the main track in a general northwesterly direction to the northernmost point of the ridge above ANTOLA VILLAGE (Beacon No. 10);

Thence following the northern foot of the ANTOLA RIDGE in a southerly direction to the BARUD WUNZ (Beacon No. 11);

Thence in a straight line in a northwesterly direction to the summit of SEREK AMBA (Beacon No. 12);

Thence due north to a point on the WOIZERO MEW-DAKIA WUNZ (Beacon No. 13);

Thence following the WOIZERO MEWDAKIA WUNZ in a westerly direction to its confluence with the SANKO-RAFEW WUNZ;

Thence following the SANKA WUNZ upstream for approximately 1000 metres to (Beacon No. 14);

Thence following the northern foot of MUCHILA AFAF to a point due north of SHARAFIT (Beacon No. 15);

Thence in a westerly direction to the summit of KUA TARARA (Beacon No. 16);

Thence in a southwesterly direction to the highest point of FALASHA RIDGE (Beacon No. 17);

Thence to the easternmost summit of CHINNA AMBA;

Thence in a westerly direction following the main ridge Of CHINNA AMBA to the summit of ANGWA AMBA;

Thence in a straight line in a southwesterly direction to the confluence of the ZARIMA AND ADERMAS streams (Beacon No. 18);

Thence following the crest of the main ridge immediately to the west of the ADERNAS WUNZ in a southwesterly

direction to the highest point of CHILKWANIT (Beacon No. 19);

Thence following a line of markers parallel to and approximately 500 metres from the escarpment edge in a southeasterly direction to the CHILKWANIT VUNZ (Beacon No. 20);

Thence following a line of marker, parallel to and approximately 500 metres from the escarpment edge in a north easterly direction to the MICHIBI TUNZ (Beacon No 21);

Thence in a straight line in an easterly direction to the point of commencement at the summit of AMMAN AMBA (Beacon No. 1).

3. Administration

The Simian National Park shall be administered in accordance with all applicable laws and regulations by the Department of Our Government hereunto duly authorized.

4. Effective Data

This Order shall come into force on the date of its publication in the Neg ant Gazeta.

Done at Addis Ababa, this 31st day of October, 1969.

TSAHAFE TAEZAZ AKLILU HABTE WOLD

Prime Minister and Minister of Pen

Regarding the institutional shaping of nature, that is, top-down politics, the documentation reveals that, for Ethiopian State officials, setting nature into a national park is, among other things, an effective means of “planting the flag” in a territory that they are struggling to control2. Simien inhabitants—mountain dwellers, agropastoralists, living between 3,000 and 4,500 metres above sea level—belatedly accepted the empire’s centralizing power. In the aftermath of the Second World War, they still rebelled against the national tax enforced by Haile Selassie (Bahru 2002, 215). Thus, when his government formalized the creation of a reserve in Simien in 1969, the operation represented an unprecedented control by the state over this region. Decree No. 59 (document 1), held at the EWCA library in Addis Ababa, defines Simien as one of the “national riches of the nation,” and this new status was far from being metaphorical. From the west to the north, all the way to the east and south of the massif, from the summit of Amman Amba in Dihuara to Antola and Adermaz, Simien was surrounded by 21 “beacons.” And, from the following year, the Department of Wildlife Conservation regulations were enforced within the borders of this nationalized territory: the national imperative for nature protection then took precedence over local practices of exploitation of the environment3.

The archives show, however, that this was not an attempt to keep an irredentist region in line, but rather to control it. From the 1960s to the present, three regimes succeeded each other in Ethiopia: the empire fell in 1974, the Marxist-Leninist regime of the Derg took over until 1991, and since then, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) runs an ethnofederal republic4. But, like its predecessors, the EPRDF faces refusal by the Simien people to be subjected to laws regulating nature. During the empire, activity reports indicate that the populations regularly destroyed the boundary beacons placed by the park wardens5. We learned from the Ethiopian Tourism Commission brochures that, in communist times, not only did the inhabitants shoot at park staff, but they also carried out “raids” against tourists6. While there is no record of such acts of rebellion since the establishment of the ethnofederal republic, minutes written by the park wardens show evidence of a passive, but perennial, resistance. Throughout the 2000s, some inhabitants received prison sentences for killing a fox or a hyena. Others were fined for cutting down trees or were sentenced to give up their crops when they expanded their fields. Many agropastoralists whose families had grown were forced to demolish the extension they had built with their own hands to house their children7. In other words, the Ethiopian state keeps on struggling to “plant the national flag” in the country’s mountainous north.

In order to promulgate itself in the environment that it defines as “natural,” the State defines the “good” use of nature, but also the “good” representations that must come along with them. This institutional shaping of the park space goes hand in hand with the cultural enterprise aiming at disseminating a set of representations of what nature is. This history is revealed by three types of sources.

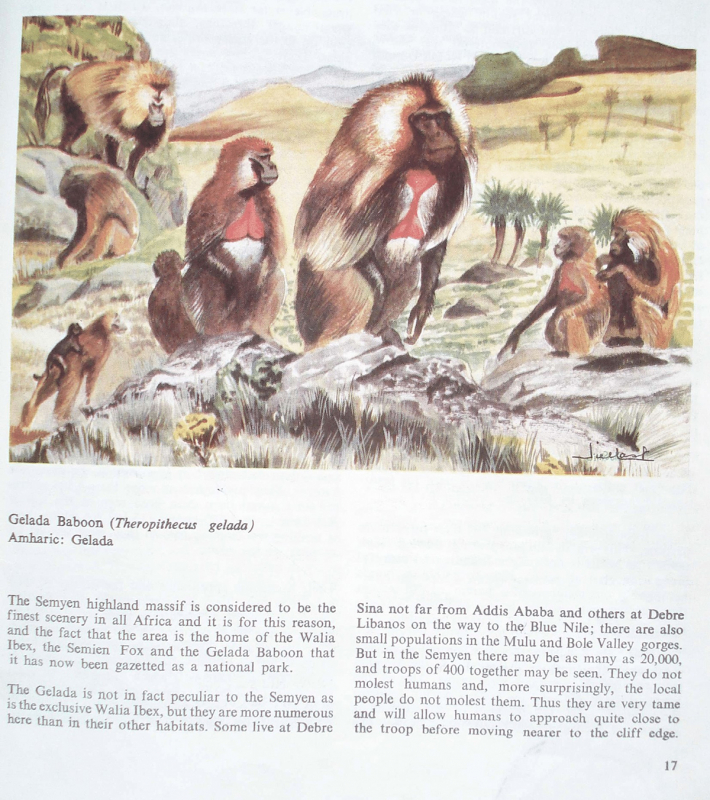

First is the tourist documentation. Published in 1982, the Endemic Mammals of Ethiopia booklet (document 2) tells us, for example, that in Simien, the Ethiopian Tourism Commission intends to offer visitors “the finest scenery in all Africa,” where they will be able to admire hordes of Gelada baboons moving in groups of up to 400 individuals. “Surprisingly,” these are lucky not to be “molested” by the “local populations.” This is the nature representation that the Ethiopian administration conveys – in English – to tourists – exclusively Western – who come to discover Simien. In 1966, it told visitors that “Ethiopia’s scenery is undoubtedly the most spectacular in Africa”8. In 1998, it boasts “the unique landscape,” “wild fauna” and “endemic flora” which earned the Simien Park its UNESCO World Heritage9 designation since 1978. And in 2011, at the park office reception in Debark, site managers presented tourists with leaflets that delivered the same message: this world natural heritage is a source of national pride10.

Document 2. Cultural Shaping of Nature (1)

Ethiopian Tourism Commission. Endemic Mammals of Ethiopia. 1982. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Tourism Commission (EWCA).

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546357.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546358/files/Ethiopian-Tourism-Commission-Endemic-Mammals-of-Ethiopia-1982.pdf.

Download transcript: https://zenodo.org/record/6546358/files/TRANSCRIPT-Ethiopian-Tourism-Commission-Endemic-Mammals-of-Ethiopia-1982.odt.

Transcript

Gelada Baboon (Theropithecus gelada)

Amharic: Gelada

The Semyen highland massif is considered to be the finest scenery in all Africa and it is for this reason, and the fact that the area is the home of the Walia Ibex, the Semien Fox and the Gelada Baboon that it has now been gazetted as a national park.

The Gelada is not in fact peculiar to the Semyen as is the exclusive Walia Ibex, but they are more numerous here than in their other habitats. Some live at Debre Sina not far from Addis Ababa and others at Debre Libanos on the way to the Blue Nile; there are also small populations in the Mulu and Bole Valley gorges. But in the Semyen there may be as many as 20,000, and troops of 400 together may be seen. They do not molest humans and, more surprisingly, the local people do not molest them. Thus they are very tame and will allow humans to approach quite close to the troop before moving nearer to the cliff edge.

Document 3. Cultural Shaping of Nature (2)

Hiking trail between Sankaber and Gich, Simien, 2013.

Author’s photographs.

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546623.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546624/files/01-Hiking-trail-between-Sankaber-and-Gich-Simien-%202013.jpg.

Activity reports produced by the EWCA complement this tourist documentation well. Since the 1960s, each of these reports indicates two types of infrastructure in Simien. The first type, quite visible, involves the dozen campsites built in the heart of the park, about every fifteen kilometers: they determine (and constrain) the hiking routes taken by visitors. The second type of infrastructure, however, is much less visible. This is linked to the trails set up by park staff between each camp, which give shape to a “hiking trail” surrounding Simien: it starts at Sankaber, crosses the Gich plateau, goes down to Chenek to extend towards Chiro Leba, then continues towards the Ras Dejen, before going up, on the north slope, to Sona, Mekarebya, and finally, Adi Arkay. When following this path, we realize that since the 1970s, Ethiopian authorities have been committed to a visual education endeavour: the visitor has no choice but to gaze at the “African” nature boasted about in leaflets, while step by step discovering, on the one hand, striking sceneries, and on the other, wild animals (document 3). However, tourists will seldom spot the villages lining the Simien Mountains which, in around 2016, were inhabited by about 5,000 inhabitants.

Hiking trails and tourist documentation deceptively show a human-free nature, but reports by foreign experts reveal how much the outside world influences this definition of “African” nature. In 1965, during the empire, Haile Selassie hired John Blower as a “Wildlife Protection Advisor” following a UNESCO recommendation. To set Simien into a natural park, the Briton advised the emperor to proceed with the “resettlement” of the populations11. After the Derg came to power, Blower was succeeded by John Stephenson. He was also British, and also advised Ethiopian authorities to protect nature from its inhabitants. To have a park of “international stature,” he wrote to the EWCA in 1975, the prerequisite is “extinguishment of human rights”12. Finally, Swiss conservationists perpetuated this paradigm of wildlife decline, from the 1980s to the mid-2000s. For 30 years, Hans Hurni, Bernhard Nievergelt, and Eva Ludi, the main consultants for UNESCO and for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), pointed at the same issue and proposed the same solution: the “overexploitation of resources” and, to curb it, the “voluntary resettlement ” of the park inhabitants13.

***

At this stage, archives finally point to a double work on nature: the dissemination of Western representations of Ethiopian nature, and Ethiopian ways of translating them into standards and practices. After the institutional and the cultural, the material shaping of ecologies remains to be addressed, that is, bottom-up politics, which can be understood by cross-referencing the (international) space of discourse and the (local) application of the regulations that follow.

When examined one by one, since the 1960s, each of the international scientific mission reports carried out in Simien describes the decline of nature, and its near extinction. But when we read these reports one after the other, another picture emerges. Take the example of the Walia Ibex, an ibex endemic to the Simien Mountains and one of the main riches that justifies the park’s designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The British ornithologist Leslie Brown recorded 150 Walia in the park in 1963, and John Stephenson, 300 in 1978. Eric Edroma and Kes Hillman Smith reported 450 in 2001. Lota Melamari, Bastian Bomhard and Guy Debonnet put the figure at 625 for 2006 and, in 2018, after the mission of Jeager Tilman carried out for IUCN, the Ethiopian authorities estimated that 925 Walia live in Simien. The increase is therefore constant. Yet, the reports are increasingly disastrous. Brown believes that the situation is “serious” in the early 1960s, Stephenson fears that the species is “lost for ever” in the late 1970s, Edroma and Smith in 2001 confess “a great fear” for the survival of the Walia, in 2018 Tilman describes a situation which is “still fragile”: systematically, for fifty years, experts deplore the imminent extinction of the Walia, which they attribute to a galloping demography. Yet, their own reports indicate that human populations in Simien are growing less rapidly than those of the Walia: the former increased from 1,500 to 5,000, the latter from 150 to 90014.

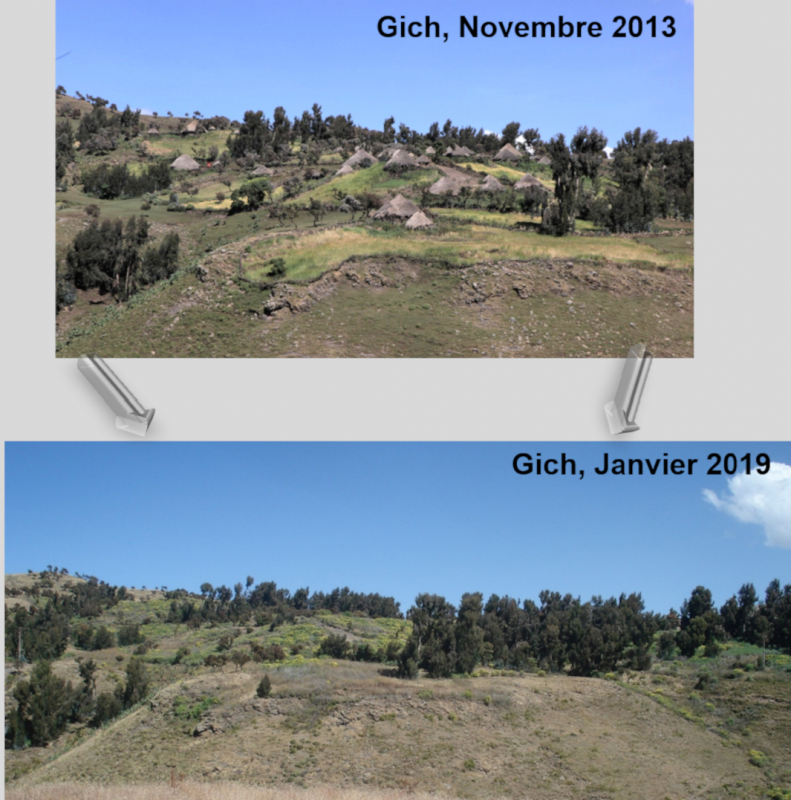

If the decline was therefore above all a myth, the laws and minutes show that the violence deployed to curb it was very real. Since 1972, in the Simien Park, the Ethiopian state has prohibited hunting, cutting trees, herd grazing, crop growing and even housing15. Because of this criminalization of daily life, as pointed out earlier, the violence crushes many agropastoralists and they also seem to retaliate against the park wardens. Moreover, other archives reveal that violence circulates even more widely, from humans to non-humans. Except in time of famine, Simien inhabitants do not hunt the Walia: this ibex lives far from their fields, on almost inaccessible ridges at an altitude of 3,500 meters, and it is barely edible. A report by Michael Mok for the US magazine Life reveals, however, that in the autumn of 1969, at the time of the park creation, Simien villagers tried to shoot all the Walia: without any ibex to protect, there would be no park to be created and no need to fear expulsion anymore (Mok 1970). Evidence of the same scenario twenty years later can be found in the report of a symposium held in Addis Ababa: when the Derg fell in 1991, fearing that the end of the civil war would mean the reopening of the park and updating of eviction plans, the inhabitants used their firearms again to get rid of the ibex16. As cruel as it is ingenious, their project failed, and they paid the final price for it in the 2010s. The UNESCO World Heritage Committee yearly reports tell us first of all that, in 2009, all 167 families from the Arkaziwe village were moved out of the park17. Then, in 2016, the 2,508 agropastoralists of the Gich village (document 4) were expelled18. Wandering around Simien confirms this information: Gich was emptied of its occupants one morning in June 2016 and, the next day, inhabitants of the surrounding villages came to retrieve the wood in their former neighbours’ houses to get warm, to feed, and to build ploughing tools. This conservation of the park space represents the last episode of the global violence revealed by the archives.

Document 4. The material shaping of nature

Village of Gich, Simien Mountains, September 2013 and January 2019.

Author’s photographs.

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546623.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546624/files/02-Village-of-Gich-Simien-Mountains-September-2013-and-January-2019.jpg.

Today, I find it appropriate to describe this violence as “global.” That said, at the end of my PhD in 2013, I had first and foremost grasped a “national” history of Ethiopian nature. It did not dismiss the importance of the West’s vision of Africa as natural and adulterated by Africans, but it focused on how the Ethiopian State both experienced these neo-Malthusian representations and instrumentalized them – because, for its leaders, having the nation recognized from the outside is a constraint that also enables them to better promulgate it from within. This story stems as much from the cross-referencing of collected sources as from the theoretical framework I had chosen when I set up my first research question, that is, the struggles at play in setting up nature as national park. This framework enabled me to collect archives that were meaningful for the understanding of nature as being the subject of a national struggle at the institutional, cultural, and material levels. But these archives also told other stories, which I had failed to hear.

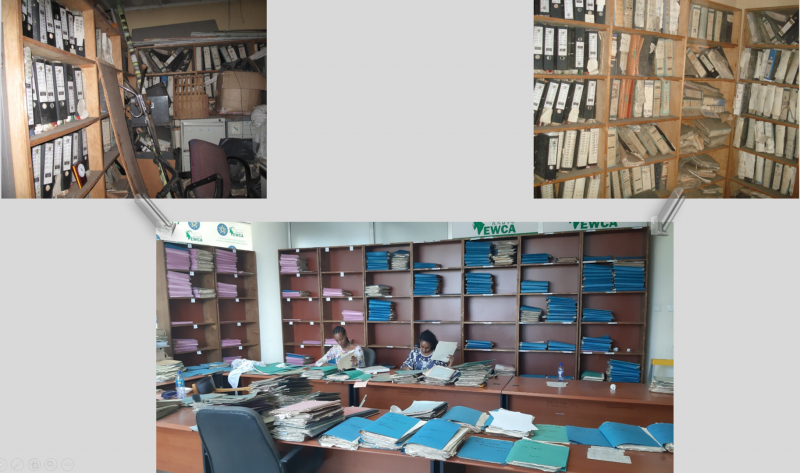

A global history of natural heritage in the South

“These boxes? It’s dead files, we’ll put them in the storage.” This is how, in the summer of 2016, the head of the EWCA library told us about a former Italian prison, converted in the early 1970s into a storage place by the Department of Conservation which had just become the EWCO (“O” for Organization). This discovery was soon to take up all of our time.

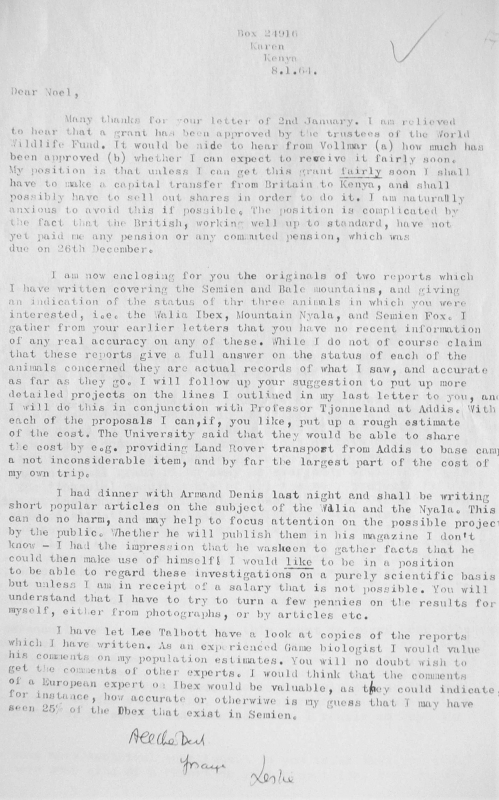

For over a month, we had been working with Kidanemariam Woldegiorgis Ayalew at the EWCA Library. The former director of the Lalibela Cultural Centre in Ethiopia, trained in heritage history at three universities in Paris, Padua and Evora, Kidane19 is a research engineer and manager of heritage projects. In 2015, in order to perpetuate the partnership initiated with the EWCA, we had started a modest project for digitizing archival collections on Ethiopian natural heritage. We then began photographing the twelve thousand pages contained by ten binders stored in the library. They all had the same inscription on their spine: “JB” (document 7). They notably included correspondence exchanged by international conservation experts during the 1960s. For example, in the ninth binder, we found about fifty letters signed by Leslie Brown.

The letter dated January 8th, 1964 (document 5) is representative of all of Brown’s correspondence. That day, he wrote to someone called Noël Simon about a field grant awarded by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). We gather from this letter that the grant would enable him to continue living in Kenya where the British were late paying him his “pension.” It seems that Leslie Brown was a wildlife specialist, as two recent reports on the Nyala in the Bale Mountains of Ethiopia, and on the Simien Walia and Simien fox, were enclosed with his letter. He then explained to Simon that the University of Addis Ababa could pay for the transport costs necessary to do the project he requested funding for. Brown seemed to be seeking funding urgently. He explained that he was reluctant to produce “popular” articles for the wildlife filmmaker Armand Denis, but was willing to do so if he failed to get a salary for pursuing a purely scientific activity. Finally, Brown said he was in touch with Lee Talbot. He asked this wildlife biologist for feedback on his reports on the Walia Ibex; he suggested that Simon disseminate these reports to other European experts.

Document 5. A network of heritage makers

Letter from Leslie Brown to Noël Simon. Karen (Kenya), January 8th, 1964 (EWCA, “John Blower” collection: BLO/7/Scientific Issues).

Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority.

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546386.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546681/files/Letter-from-Leslie-Brown-to-Noel-Simon-1964-01-08.pdf.

Download transcript: https://zenodo.org/record/6546681/files/Letter-from-Leslie-Brown-to-Noel-Simon-1964-01-08.odt.

Transcript

Box 24916

Karen

Kenya

8.1.64.

Dear Noel,

Many thanks for your letter of 2nd January. I am relieved to hear that a grant has been approved by the trustees of the World Wildlife Fund. It would be nice to hear from Vollmar (a) how much has been approved (b) whether I can expect to receive it fairly soon.

My position is that unless I can get this grant fairly soon I shall have to make a capital transfer from Britain to Kenya, and shall possibly have to sell out shares in order to do it. I am naturally anxious to avoid this if possible. The position is complicated by the fact that the British, working well up to standard, have not yet paid me any pension or any commuted pension, which was due on 26th December.

I am now enclosing for you the originals of two reports which I have written covering the Semien and Bale mountains, and giving an indication of the status of thr [sic] three animals in which you were interested, i.e. the Walia Ibex, Mountain Nyala, and Semien Fox. I gather from your earlier letters that you have no recent information of any real accuracy on any of these. While I do not of course claim that these reports give a full answer on the status of each of the animals concerned they are actual records of what I saw, and accurate as far as they go. I will follow up your suggestion to put up more detailed projects on the lines I outlined in my last letter to you, and I will do this in conjunction with Professor Tjonneland at Addis. With each of the proposals I can, if, you like, put up a rough estimate of the cost. The University said that they would be able to share the cost by e.g. providing Land Rover transport from Addis to base camp a not inconsiderable item, and by far the largest part of the cost of my own trip.

I had dinner with Armand Denis last night and shall be writing short popular articles on the subject of the Walia and the Nyala. This can do no harm, and may help to focus attention on the possible project by the public. Whether he will publish them in his magazine I don’t know – I had the impression that he was keen to gather facts that he could then make use of himself! I would like to be in a position to be able to regard these investigations on a purely scientific basis but unless I am in receipt of a salary that is not possible. You will understand that I have to try to turn a few pennies on the results for myself, either from photographs, or by articles etc.

I have let Lee Talbott have a look at copies of the reports which I have written. As an experienced Game biologist I would value his comments on my population estimates. You will no doubt wish to get the comments of other experts. I would think that the comments of a European export on Ibex would be valuable, as they could indicate, for instance, how accurate or otherwise is my guess that I may have seen 25% of the Ibex that exist in Semien.

In itself, this letter already provides a great deal of information. And it becomes a tremendous source when it is cross-referenced with Brown’s other letters, and then complemented with the documentation that I had been collecting during my PhD. This correspondence suggests a global environmental intervention, far from the national focus I had chosen during my PhD.

Born in England in 1917, Leslie Brown grew up in India. He returned to Britain to train in ornithology and agronomy and then, at the beginning of the Second World War, he went to explore British Africa. Brown joined Nigeria’s Agricultural Corps in 1940 and Kenya’s Department of Agriculture in 1946. There, he was appointed deputy director ten years later, and director in 1962. Then, in 1963, Kenya became a sovereign state and Brown an unemployed colonial administrator. He then became an agronomy adviser to the Kenyan authorities and an expert throughout East Africa for international conservation institutions (Everett 1981). He arrived in Ethiopia wearing this second hat; Unesco had mandated him to locate potential national parks, especially in the Simien and Bale mountains.

As his letter shows, Brown also worked with Simon Noël, Friedrich Vollmar, Armand Denis, and Lee Talbot. Noël was based in Morges, Switzerland, where he was the Secretary-General of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Vollmar also worked at Morges, as the first Secretary-General of the WWF, founded in 1961. Denis was the most important wildlife filmmaker in the 1960s, working in reserves in Africa and Southeast Asia, from the former Belgian Congo to Burma. Talbot was a biologist in Kenya, where he helped create the Serengeti National Park, and in the mid-1960s he moved to Brussels to work for the Belgian branch of IUCN, where he contributed to the development of African conservationist policies. Through Brown’s correspondence, a whole network of nature professionals is revealed, involving international institutions, conservation experts and naturalists. This is what I then wanted to study.

After photographing all the documentation contained in these ten binders, Kidane and I asked whether there were any other similar sources. From the library on the 8th floor, we then went down to the 7th floor, where the EWCA staff showed us two cardboard boxes where we found more archives: the famous “dead files,” intended to be sent to “storage.” The person in charge of the storage warehouse took us there two days later, in the Lideta district. We discovered a vast wasteland strewn with out-of-service all-terrain vehicles but still showing, on their doors, marks of the sponsors who gave them to the Ethiopian authorities: “London Zoological Society,” “WWF,” “Unesco.” Then, at the top of the field, was the old Italian prison in which four rooms had been turned into a storage place. One contained printers and defective office equipment, two other contained tyres, tools or old newspapers, and the fourth, about 800 binders similar to those in the EWCA, stored on shelves along the walls.

A first survey quickly convinced us of the incredible wealth of this documentation. Correspondence between colonial administrators and international experts who once worked in Ethiopia, programmes for the development of Ethiopian parks recognised by Unesco, records of international conferences, files of the EWCA staff sent to Tanzania to train at the College of African Wildlife Management, mission reports from scientists from IUCN, WWF or the Wildlife Conservation Society…: this enabled us to create Ethiopia’s first archive collection in environmental history

This project took us five years. After being hired at University of Rennes 2 in 2017, I was granted at the end of 2018 an ANR project entitled PANSER, “PAtrimoines Naturels aux Suds : une histoire globale à Échelle Réduite” (“Natural Heritages in the South: A Global History on a Reduced Scale”). In this context, in 2019, we started developing an institutional partnership between the Tempora laboratory in Rennes, the EWCA in Addis Ababa, and the French Centre for Ethiopian Studies (CFEE). In parallel, we used the skills of an archivist trained at the École des Chartes. For two months, as part of her graduation project, Pia Rigaldiès helped us organizing the work ahead: filing archives, building bespoke library shelves, ordering 650 archive boxes, making several thousand paper pouches, and purchasing equipment to maintain or even restore the documentation. Then, at the beginning of 2020, once the partnerships had been officially established, we organised the relocation, transport, and storage of all the binders from the warehouse to the new EWCA headquarters in Yobek (document 6). Finally, Kidanemariam Woldegiorgis and I hired Lidya Adane Workie and Kalehiwot Ayele Gebregiorgis, who had recently graduated in Ecology and Economics from Addis Ababa University. With them, for a year and a half, we dusted, sorted and archived almost a million archive pages. My first experience with the Ethiopian archives had shown me that it did not make sense to classify the documents in terms of social groups being providers of sources (administrators, entrepreneurs, scientists, etc.) or themes (institutional, cultural, material, etc.). Thanks to the archival know-how of Pia Rigaldiès, we then created a classification in fourteen categories. These enabled us to easily spot an archive in the documentary mass by avoiding trapping it in a predefined interpretation grid as much as possible: Human Resources; Protected Areas; Wildlife Management; Hunting; General Development Programs; Projects, Studies and Research; Laws and Regulations; Budget and Finance; International Relations; Correspondence; Tourism; Photographs, Films and Maps; Education.

Document 6. An archival collection dedicated to the environmental history of Ethiopia

EWCA warehouse, Lideta district, July 2016; EWCA offices, Yobek district, April 2021.

Photographs by Guillaume Blanc (2016) and Kidanemariam Woldegiorgis Ayalew (2021).

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546623.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546624/files/03-EWCA-warehouse-Lideta-district-2016_EWCA-offices-Yobek%20district-2021.jpg.

The first sources studied in this collection contributed to the ANR PANSER research, a program that I coordinated with the help of two colleagues in particular, Mathieu Guérin (Inalco) and Grégory Quenet (University of Versailles St-Quentin-en-Yvelines). Starting from the trajectories of experts in Ethiopia, we attempted to identify and then cross-reference similar global circulations in Kenya, Zanzibar, Seychelles and Colonial Cochinchina, Cambodia and Malaysia. Our research was greatly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. However, the archives that we could collect and assemble opened up three avenues for reflection.

First, in Africa as in Asia, in each nation-state, throughout the twentieth century, the making of nature seems to be punctuated by meetings between (ex) mainland and colonies. In Malaysia, for example, from the 1930s to the early 1970s, the management of protected areas appeared to evolve through negotiations involving, on the one hand, Malaysian sultans who were first colonial auxiliary agents then later leaders of the Malaysian Federation, and, on the other hand, British colonial administrators, who converted into international experts in the aftermath of independence. Beyond these (post)colonial relationships, the archives of national and international conservation institutions show career paths which are punctuated by intra-continental circulation, again in Asia as in Africa, and again from the beginning of the twentieth century to the present. Sometimes working in the Congo nature reserves, sometimes in those of Ethiopia, we find, for example, from the 1950s to the 1970s, the ornithologist Leslie Brown; then, from the 1980s to the 2000s, the zoologist Kes Hillman Smith (coordinator at the Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation and consultant for IUCN). Both in Ethiopia and Congo, Brown and Hillman worked closely with national authorities, but also with tourist guides and inhabitants of protected areas. Finally, these nature professionals seem to be at the centre of trans-continental circulation, which can be identified firstly in forest reserve management programmes or hunting regulations produced by French or British colonial administrations, and secondly in scientific mission reports written by experts from international conservation institutions. These archives indicate, for example, that in Vietnamese Cochinchina in the 1920s, members of the commissions on hunting regulation based their work on that carried out in French West Africa. Also, in Seychelles and Malaysia, ten years before and ten years after independence, guidelines for nature policies were defined by the same man, the British biologist John Procter.

Following the trajectories of these conservationists led us to give up our a spatio-temporal approach of “what the North does in the South” or “before and after the decolonization of the 1960s.” Rather, we were led to rethink the contemporary geography and history of the construction of nature and state in the South. Throughout the twentieth century, there was a continuous circulation of zoologists, botanists, and foresters (1900–1930), biologists, agronomists, and experts (1930–1980), developmentalists, ecologists, and consultants (1980–present). These professionals disseminated knowledge and naturalistic practices and, in so doing, promoted the incorporation of local ecologies into global biopolitics, to the point of giving substance to an Afro-Asian heritage area. This then seems to evolve over a chronology that does not follow the logic dictated by the independence discontinuity. From 1900 to 1930, the creation of hunting reserves seems to legitimize the imperial appropriation of natural resources and favour the creation of the colonial state. Then, from 1930 to 1980, beyond independence, the proliferation of national parks suggests consistency in the ways nature and its inhabitants were governed. Finally, since the 1980s, the development of the biodiversity zone label seems to flag the way in which, in the South, states are now instrumentalising global categories on a daily basis to improve control over their territories and citizens – the latter instrumentalise these global categories just as much to evade state power, or at least to better negotiate with its representatives.

This history of governance of nature and people is a project that we are now pursuing, along with a dozen colleagues. We hypothesized that, by examining the global encounters that took place in the tropics between experts, leaders and inhabitants from 1900 to the present day, it is possible to fully abandon a colonization-decolonization chronology. Rather, it is an attempt to place this Afro-Asian area in an endogenous chronology, that is, in a global history of the South, seen from the South. We believe that three prerequisites are necessary to achieve this objective. First, there is the collective dimension of research: faced with histories of the governance of nature that are as much national as international, only the pooling and the cross-referencing of situated research will allow us to shed light on a global history of the South, seen from the South (Blanc, Guérin and Quenet 2022). Then, we need to consider the time taken for research: faced with archives produced by “heritage makers” embedded in international networks, only prolonged and repeated stays in the archives will enable us to find the voice of local agents, experts, and national environmentalists and, thus, to shed light at ground level on the conflicts and negotiations at play in the global governance of nature.

Finally, rethinking this contemporary history requires the answer to a central question: if, when it comes to nature conservation, there is a colonial “before” and a postcolonial “after,” how does the continuity between the two take place in practice? Heritage studies have shed light on the reproducibility of a tropical ecology management model developed in the early twentieth century, then generalized by various international organizations after the 1960s. This pioneering (Cormier-Salem et al. 2002) and still valid approach (Cormier-Salem et al. 2016), however, did not explain how and why nature policies that were developed in a colonial context continued to be globalized after independence. In this regard, postcolonial studies can provide several possible answers. Their researchers have defined “postcolonial” as both a method and a process. The postcolonial method consists in rethinking North/South relationships in terms of hybridization rather than domination. Like everywhere in the world, contemporary African societies are subjected to the global circulation of power as much as they participate in it: they must therefore be studied as the engine of their world history (Cooper 2015). As a process, postcolonialism also refers to the intermingling of the so-called “colonial” and “post-colonial” periods (with a dash), that is to say, not to the succession of time periods but to their accumulation: the intertwining of the past and present establishes the historicity of postcolonial societies (without a dash) (Mbembe 2000). But here again, the way these temporalities fit together concretely remains to be explained: where, when and how continuity takes place? Here, we hypothesized that between “before” and “after” independence, a “postcolonial event” as such seems to make the link, throughout the 1960s. This is a pivotal period during which colonial administrators converted into international experts and, in so doing, associated with, opposed, and confronted the leaders and inhabitants of now-independent African states.

The EWCA archives lie at the origin of this hypothesis. They urge us to consider postcolonialism as a method, a process, but also as a moment in its own right: that of a postcolonial Africa whose genesis is located both in time and in space.

Much individual and collective research is needed to explore this history. For this purpose, the archives are now available on site, in Yobek, at the EWCA headquarters. A digitisation project is also underway, but its implementation raises financial, technical, and ethical problems. At the financial level, neither the French Centre for Ethiopian Studies nor the Ethiopian administration have the means to hire the staff needed to digitize nearly a million pages in various states of preservation. At the technical level, the issue is about availability: once the archives have been digitised, how can they be put online: a website hosted by the CFEE or EWCA? Lastly, what should be the criteria for their availability: free of charge for Ethiopians and a fee-based service for foreigners? This system is currently in place for carrying out research in one Ethiopian national park: any foreigner, whether doctoral students, researchers, or producers of documentary projects, must pay $1,000 to carry out a research project requiring entry into the park. This is the ethical question: will there be a cost to access Ethiopian archival sovereignty? Some members of the EWCA wish so. The digitization of archives would be a factor in the “African modernity” of which Ethiopia is the spearhead, and their commodification would be a means of developing Ethiopian history while asserting the monopoly of the State over it. On the contrary, some French researchers consider digitalisation as a potential danger. Accessing the archives would guarantee Ethiopian sovereignty in the short term, but the risk of dispossession would be great, since, in the long term, the history of the country could well be written from abroad by foreigners.

Far from being resolved, these disagreements refer directly to the postcolonial dimension of history, that is, to the way in which encounters between North and South determine today the way history is written, just as they determined yesterday the way in which history happened. And these postcolonial encounters are also played out in archives: those of African national administrations in general, those of the EWCA in particular and, concerning us more personally, those contained in the binders labelled “JB.”

A History of the Postcolonial Event

“This? I don’t know. Old papers I think.” I had already examined several of these documents during my PhD. At EWCA, since I lacked a descriptive catalogue of archives, I had chosen a simple method: starting from the library manager’s office, I “went around” the library from right to left, shelf after shelf, wall after wall, and took photos of the documents potential containing inform on the Simien National Park’s history. Two months later, having gone fully round the room and returned to the manager’s office, I asked her about the content of the binders sitting on the shelf just behind her desk (document 7). It was the only space left in the library to be explored.

Document 7. The “John Blower” collection

“JB” binders, Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority Library, Addis Ababa, 2016.

Author’s photographs.

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546623.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546624/files/04-John-Blowers-collection-EWCA-Library-Addis-Ababa-2016.jpg.

She allowed me to study these “old papers” the next day and, a day later, we both realized that the “JB” label found on ten binders referred to a man, John Blower, the “emperor’s advisor for the protection of wildlife” as he usually mentioned on his hand-signed documents. Blower spent five years in Ethiopia, from 1965 to 1970. In that time, he had accumulated nearly 12,000 pages of activity reports, law drafts, inventories of Ethiopian fauna and flora, management programmes, or correspondence with Ethiopian administrators and foreign conservationists. During my PhD, since these 12,000 pages were not filed and their content related to five years only, I had limited myself to collecting information about Simien only. It took me several years of research to realize the potential of these binders. In 2016, with Kidanemariam Woldegiorgis Ayalew, we photographed their entire content and, in 2019, with Pia Rigaldiès, we sorted the whole documentation, filed it in seven archive boxes, and created a rational catalogue. We remained faithful to the original classification of the binders whose content was filed in seven main categories: “Conservation and regulation of wildlife,” “Aid and international missions,” “General administrative management,” “Management of national parks,” “Tourism, safari, and hunting,” “Scientific activities” and “Correspondence.” Finally, in 2020, I started probing the entire new “John Blower” collection. This collection takes us at the heart of the “postcolonial event” which is constituted and revealed by the professional trajectories of colonial administrators converted into international experts at the turn of African independence.

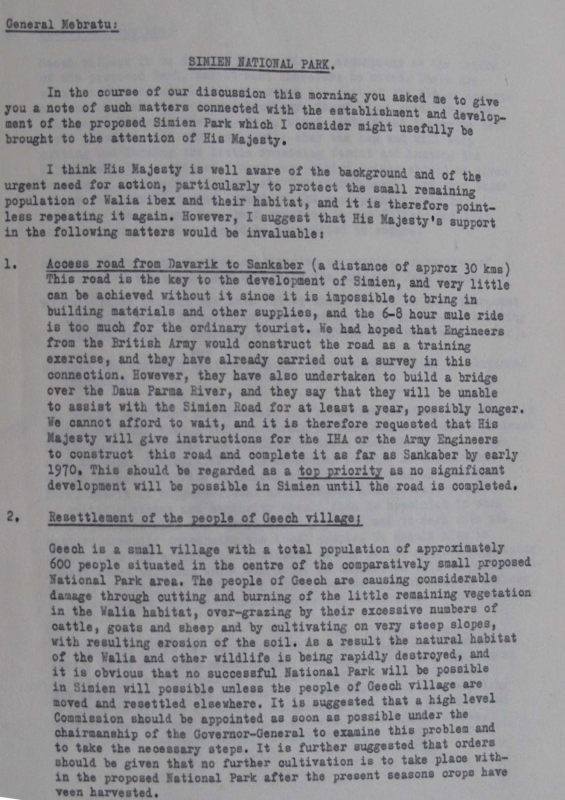

On July 16th, 1969, three and a half months before the Simien Park was officially created, Blower sent a note to the new director of the Ethiopian Department of Conservation (document 8). He asked General Mebratu to kindly pass to the emperor instructions that he deemed necessary to be applied in Simien. The first is the construction of a 30-kilometre stretch of road from the small town of Debark to the park entrance, in the village of Sankaber. This route would save tourists a day of ride on mule back and should therefore be a “top priority.” Without it, “no significant development will be possible in Simien,” writes Blower, adding that “no successful national park will be possible in Simien until the inhabitants of the village of Gich [Geech] are moved and resettled elsewhere.” The second advice made by the Emperor’s advisor was to empty the mountains of their inhabitants and, more specifically, of the 600 agropastoralists in Gich who, according to him, cause “considerable damage through cutting and burning of the little remaining vegetation in the Walia habitat, overgrazing by their excessive numbers of cattle, goats and sheep, and by cultivating on very steep slopes, with resulting erosion of the soil.” Blower recommends their eviction to set nature into a park and present it to tourists: according to him, it is first necessary to return the site to nature – that is, to depopulate it by converting a territory of daily lives into a place of temporary visits.

Document 8. Depopulating, returning to nature and perpetuating the colonial myth

Letter from John Blower to General Mebratu. Addis Ababa, July 16th, 1969 (EWCA, “John Blower” Collection: BLO/4/Simien National Park).

Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority.

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546406.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546407/files/Letter-from-John-Blower-to-General-Mebratu.Addis-Ababa-July-16th-1969.jpg.

Download transcript: https://zenodo.org/record/6546407/files/TRANSCRIPT-Letter-from-John-Blower-to-General-Mebratu.Addis-Ababa-July-16th-1969.odt.

Transcript

General Mebratu:

SIMIEN NATIONAL PARK.

In the course of our discussion this morning you asked me to give you a note of such matters connected with the establishment and development of the proposed Simien Park which I consider might usefully be brought to the attention of His Majesty.

I think His Majesty is well aware of the background and of the urgent need for action, particularly to protect the small remaining population of Walia ibex and their habitat, and it is therefore pointless repeating it again. However, I suggest that His Majesty’s support in the following matters would be invaluable:

1. Access road from Davarik to Sankaber (a distance of approx 30 kms)

This road is the key to the development of Simien, and very little can be achieved without it since it is impossible to bring in building materials and other supplies, and the 6-8 hour mule ride is too much for the ordinary tourist. He had hoped that Engineers from the British Army would construct the road as a training exercise, and they have already carried out a survey in this connection. However, they have also undertaken to build a bridge over the Daua Parma River, and they say that they will be unable to assist with the Simien Road for at least a year, possibly longer. We cannot afford to wait, and it is therefore requested that His Majesty will give instructions for the IHA or the Army Engineers to construct this road and complete it as far as Sankaber by early 1970. This should be regarded as a top priority as no significant development will be possible in Simien until the road is completed.

2. Resettlement of the people of Geech village;

Geech is a small village with a total population of approximately 600 people situated in the centre of the comparatively small proposed National Park area. The people of Geech are causing considerable damage through cutting and burning of the little remaining vegetation in the Walia habitat, over-grazing by their excessive numbers of cattle, goats and sheep and by cultivating on very steep slopes, with resulting erosion of the soil. As a result the natural habitat of the Walia and other wildlife is being rapidly destroyed, and it is obvious that no successful National Park will be possible in Simien will possible unless the people of Geech village are moved and resettled elsewhere. It is suggested that a high level Commission should be appointed as soon as possible under the chairmanship of the Governor-General to examine this problem and to take the necessary steps. It is further suggested that orders should be given that no further cultivation is to take place within the proposed National Park after the present seasons crops have been harvested.

This note illustrates the continuation of the colonial myth of an African Eden: that of a nature that used to be virgin, wild, and animal-rich, but which is today overcrowded, spoiled, and threatened with imminent extinction. Historians have studied this myth extensively, both in its colonial origins (Adams and McShane 1996) and in its postcolonial extensions (Adams and Mulligan 2003). But Blower’s archives shed light on how the myth was perpetuated: through the employment of European staff trained in the colonies.

John Blower was a former soldier with the Royal West African Frontier Force. After the Second World War, he graduated in forestry at the University of Edinburgh and then worked in the East African colonies of the British Empire: in Tanganyika, Kenya and then in Uganda, where he was chief warden of the colony’s national parks. He lost his job at independence in 1962, but this period of inactivity was short-lived. Indeed, three years later, his compatriot Leslie Brown interceded on his behalf with UNESCO which, in turn, recommended him to the Ethiopian Department of Conservation. Blower went to Ethiopia in 1965 and, just a few months after his arrival, he called on other Western “experts” of African nature.

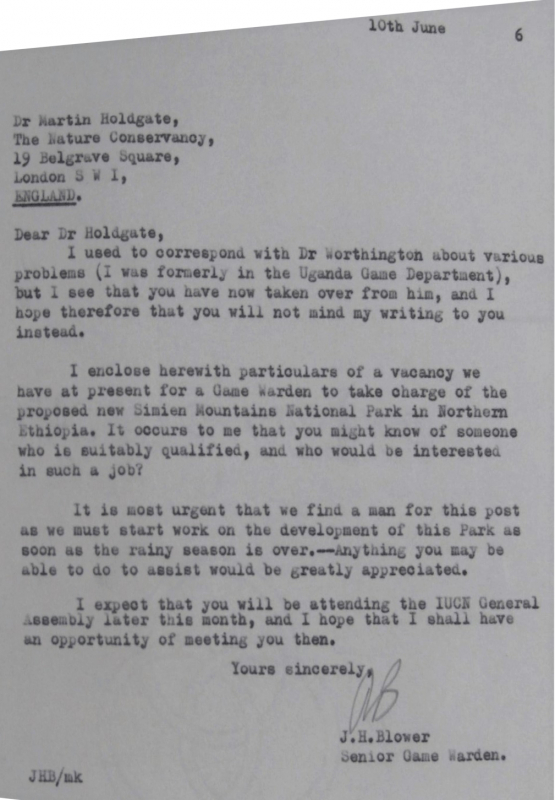

Archives show that, as early as the summer of 1966, he got in touch with colleagues he had met in Kenya and Tanzania, with former chief warden of East African colonies, with North American scientists, and with several heads of international conservation institutions. For example, Blower was in touch with Martin Holdgate (document 9). The Director of the Nature Conservancy, the British National Parks Agency, Holdgate is an active member of IUCN and will become its Director twenty years later. Blower relied on men like him to hire wardens for the future Ethiopian national parks: men who will organize the construction of tourist infrastructure, who will make an inventory of the fauna and flora, and who will patrol the park area to enforce regulations. On June 10th, 1966, he wrote to Holdgate for the advertising of a job vacancy for the position of Simien’s warden. Then, in the following months, presumably after meeting with his interlocutor at the IUCN yearly meeting, John Blower repeated his request: he’s looking for “suitably qualified men” to build reserves in Awash in the east of the country, Omo in the south, Gambella in the west, and Eritrea in the north.

Document 9. The Conservationist International (1)

Letter from John Blower to Martin Holdgate. Addis Ababa, June 10th, 1966 (EWCA, “John Blower” collection: BLO/2/About John Blower’s employment).

Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority.

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546427.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546428/files/Letter-from-John-Blower-to-Martin-Holdgate.Addis-Ababa-June-10th-1966.pdf.

Download transcript: https://zenodo.org/record/6546428/files/TRANSCRIPT-Letter-from-John-Blower-to-Martin-Holdgate.Addis-Ababa-June-10th-1966.odt.

Transcript

10th June … … 6

Dr Martin Holdgate,

The Nature Conservancy,

19 Belgrave Square,

London S W I,

ENGLAND.

Dear Dr Holdgate,

I used to correspond with Dr Worthington about various problems (I was formerly in the Uganda Game Department), but I see that you have now taken over from him, and I hope therefore that you will not mind my writing to you instead.

I enclose herewith particulars of a vacancy we have at present for a Game warden to take charge of the proposed new Simian Mountains National Park in Northern Ethiopia. It occurs to me that you might know of someone who is suitably qualified, and who would be interested, in such a job?

It is most urgent that we find a man for this post as we must start work on the development of this Park as soon as the rainy season is over.—Anything you may be able to do to assist would be greatly appreciated.

I expect that you will be attending the IUCN General Assembly later this month, and I hope that I shall have an opportunity of meeting you then.

Yours sincerely,

J.H.Blower

Senior Game warden.

JHB/mk

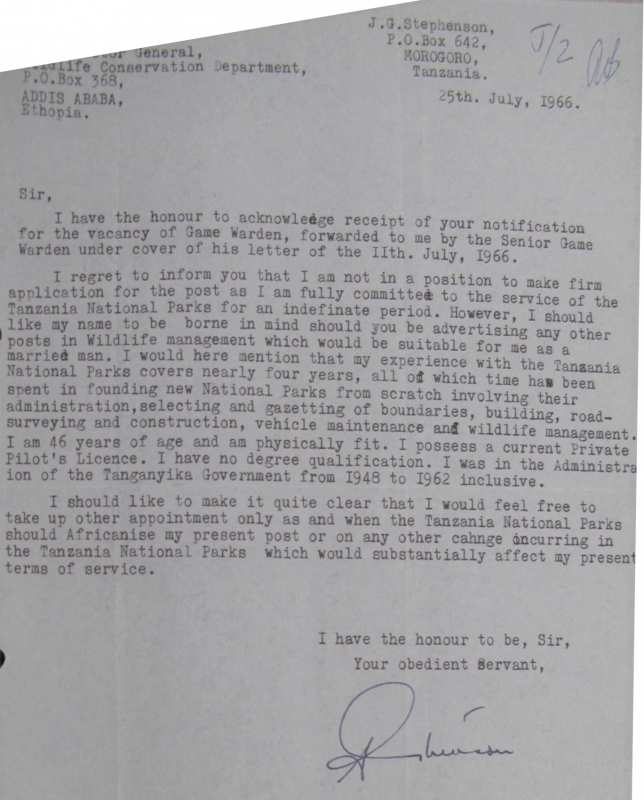

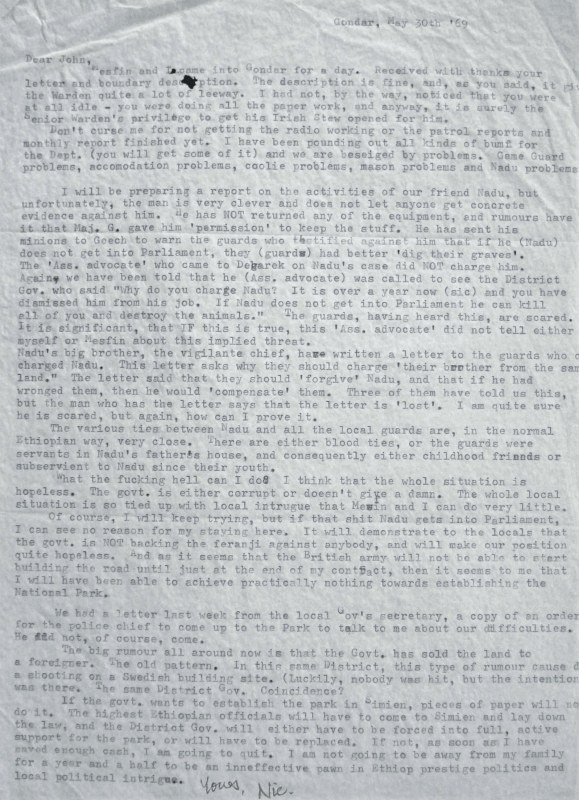

In his binders, Blower kept the dozens of applications he received from agronomists, foresters, or reserve wardens. Some worked in Britain and Italy for UN agencies, others were employed at Canadian or US universities, and many were still based in East Africa, from Southern Rhodesia to Kenya. John Stephenson, whose name I had already noted during my PhD, was one of them. At the time of the Derg, Stephenson worked so closely with North American conservationists as an advisor to the EWCA that I had identified him as a US citizen. But the letter he sent to John Blower in July 1966 (document 10) indicates that he was British. In that letter, Stephenson asked his compatriot to keep his file in case a position as wildlife manager were to be vacated at a later date. He would only apply, he wrote, “as and when the Tanzania National Parks should Africanize his present post.” Indeed, after ten years serving the British Tanganyika government, Stephenson had been working for the Tanzanian Republic for four years. He wrote that he was working on “founding new National Parks from scratch, involving their administration, selection and gazetting of boundaries, building, road surveying and construction, vehicle maintenance and wildlife management.”

Document 10. The Conservationist International (2)

Letter from John G. Stephenson to John Blower. Morogoro, Tanzania, July 25th, 1966 (EWCA, “John Blower” collection: BLO/2/Game Warden’s Application).

Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority.

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546441.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546442/files/Letter-from-John-G.Stephenson-to-John-Blower.Morogoro-Tanzania-July-25th-1966.pdf.

Download transcript: https://zenodo.org/record/6546442/files/TRANSCRIPT-Letter-from-John-G.Stephenson-to-John-Blower.Morogoro-Tanzania-July-25th-1966.odt.

Transcript

[…]

[TOP LEFT]

[Director] General,

Wildlife Conservation Department,

P.O.Box 368,

ADDIS ABABA

Ethiopia.

[TOP RIGHT]

J. G. Stephenson,

P.O.Box 642,

MOROGORO,

Tanzania.

25th. July, 1966.

Sir,

I have the honour to acknowledge receipt of notification for the vacancy of Game Warden, forwarded to me by the Senior Game Warden under cover of this letter of the IIth. July, 1966.

I regret to inform you that I am not in a position to make firm application for the post as I am fully committed to the service of the Tanzania National Park for an indefinate period. However, I should like my name to be borne in mind should you be advertising any other posts in Wildlife management which would be suitable for me as a married man. I would here mention that my experience with the Tanzania National Parks covers nearly four years, all of which time has been spent in founding new National Parks from scratch involving their administration, selecting and gazetting of boundaries, building, road-surveying and construction, vehicle maintenance and wildlife management. I am 46 years of age and am physically fit. I possess a current Private Pilot’s Licence. I have no degree qualification. I was in the Administration of the Tanganyika Government from 1948 to 1962 inclusive.

I should like to make it quite clear that I would feel free to take up other appointment only as and when the Tanzania National Parks should Africanise my present post or on any other change occurring in the Tanzania National Parks which would substantially affect my present terms of service.

I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient Servant,

This correspondence seems to shed even more light on the ways the colonial myth of African nature was perpetuated. Through major Western conservation institutions, former colonial administrators such as Blower and Stephenson converted into international experts. They then seem to give shape to a real Internationale of heritage makers: before the “Africanization” of administrations that had become national, they clearly strived to return African parks to nature, that is, to keep working in the field towards idealised ecologies that are virgin, wild, and depopulated.

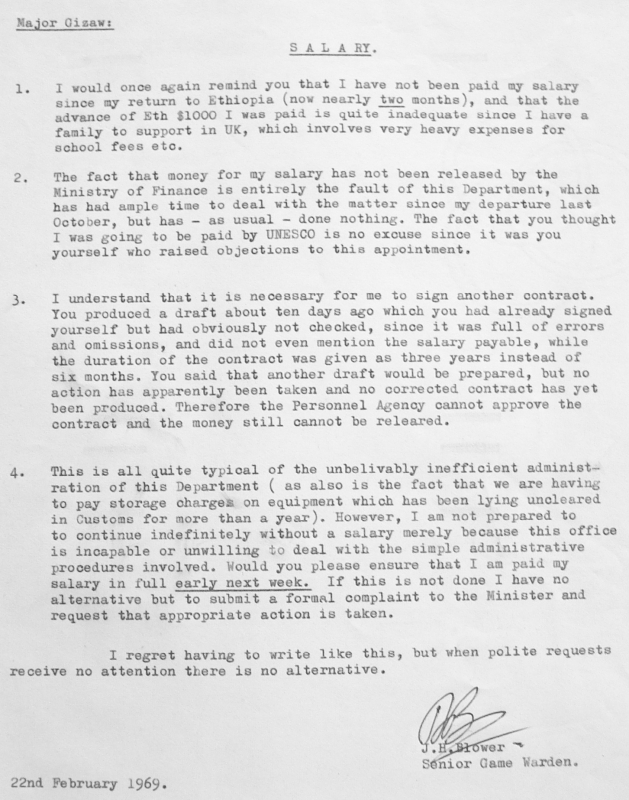

What else do these archives tell us? At first sight, we can read the sign of a rising neocolonial governance of nature in the aftermath of independence. This appears in particular through the relationship between Blower and Major Gizaw Gedlegeorgis, the first director of the Ethiopian Department of Conservation. On February 22nd, 1969, in a memo sent to Gizaw (document 11), Blower complained of not having been paid for two months: Blower’s contract should have been renewed for six months, but Gizaw had prepared a document mentioning a three-year extension and, in the revised version, the error was not corrected, and the salary payable was not specified. Blower then protested against the alleged “unbelievably inefficient administration of this department,” “incapable or unwilling to deal with the simple administrative procedures.” He threatened to complain personally about Gizaw to the Finance Minister if nothing is done “early next week,” and concludes: “I regret having to write like this, but when polite requests receive no attention there is no alternative.” He finally signed his memo with the title “Senior Game Warden.” There are no traces of such a position in the documents produced by the Ethiopian administration, and yet Blower claims it for himself in many documents, a sign that he has lost little or nothing of the superiority complex that affected colonizers in general, and accompanied his presence in East Africa in particular.

Document 11. A Neocolonial Governance of Nature

Letter from John Blower to Major Gizaw. Addis Ababa, February 22nd, 1969 (EWCA, “John Blower” collection: BLO/7/Miscellaneous).

Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority.

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546455.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546456/files/Letter-from-John-Blower-to-Major-Gizaw.Addis-Ababa-February-22nd-1969.pdf.

Download transcript: https://zenodo.org/record/6546456/files/TRANSCRIPT-Letter-from-John-Blower-to-Major-Gizaw.Addis-Ababa-February-22nd-1969.odt.

Transcript

Major Gizaw:

SALARY.

1. I would once again remind you that I have not been paid my salary since my return to Ethiopia (now nearly two months), and that the advance of Eth $1000 I was paid is quite inadequate since I have a family to support in UK, which involves very heavy expenses for school fees etc.

2. The fact that money for my salary has not been released by the Ministry of Finance is entirely the fault of this Department, which has had ample time to deal with the matter since my departure last October, but has – as usual – done nothing. The fact that you thought I was going to be paid by UNESCO is no excuse since it was you yourself who raised objections to this appointment.

3. I understand that it is necessary for me to sign another contract. You produced a draft about ten days ago which you had already signed yourself but had obviously not checked, since it was full of errors and omissions, and did not even mention the salary payable, while the duration of the contract was given as three years instead of six months. You said that another draft would be prepared, but no action has apparently been taken and no corrected contract has yet been produced. Therefore the Personnel Agency cannot approve the contract and the money still cannot be releared.

4. This is all quite typical of the unbelivably inefficient administration of this Department (as also is the fact that we are having to pay storage charges on equipment which has been lying uncleared in Customs for more than a year). However, I am not prepared to to [sic] continue indefinitely without a salary merely because this office is incapable or unwilling to deal with the simple administrative procedures involved. Would you please ensure that I am paid my salary in full early next week. If this is not done I have no alternative but to submit a formal complaint to the Minister and request that appropriate action is taken.

I regret having to write like this, but when polite requests receive no attention there is no alternative.

J.H.Blower

Senior Game Warden.

22nd February 1969.

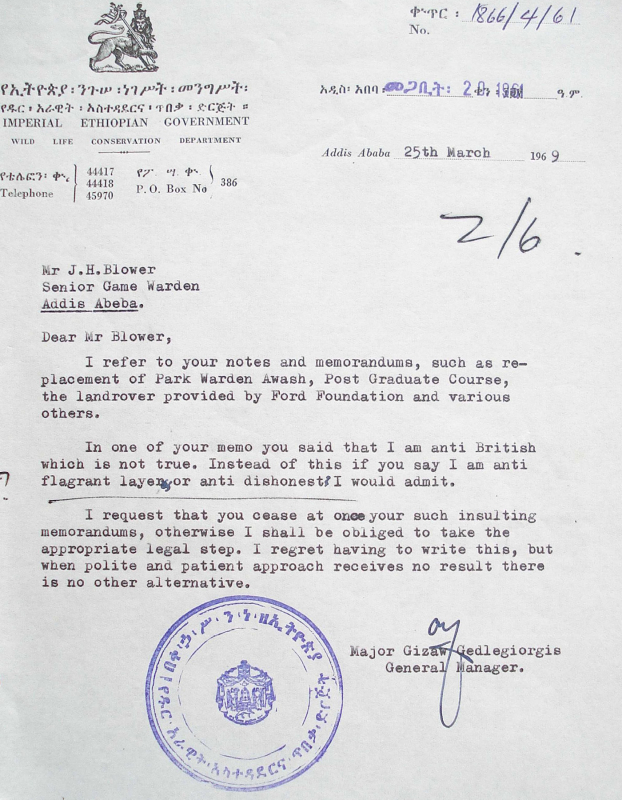

Major Gizaw’s reply (Document 12), however, indicates that North-South relationships were then more about negotiation than domination. In a memo sent to John Blower on March 25th, 1969, Gizaw accepted his title of “Senior Game Warden” on this occasion, and took note of his requests: the replacement of the Awash warden, a postgraduate course, an all-terrain vehicle provided by the Ford Foundation, etc. But the director of the Department of Conservation seems far from complying with Blower’s demands. “In one of your memo you said that I am anti-British which is not true,” wrote the major. “If you say I am anti flagrant layer and anti-dishonest I would admit,” he protested and in turn threatened the expatriate with “the appropriate legal step” if he continued to produce such “insulting” memos. And Gizaw concludes with irony: “I regret having to write this, but when polite and patient approach receives no result, there is no other alternative.”

Document 12. A postcolonial governance of nature

Letter from Major Gizaw Gedlegeorgis to John Blower. Addis Ababa, March 25th, 1969. EWCA Archives, “John Blower” collection (BLO/7/Miscellaneous).

Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority.

Permanent identifier: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6546485.

Download file: https://zenodo.org/record/6546703/files/Letter-from-Major-Gizaw-Gedlegeorgis-to-John-Blower.Addis-Ababa-March-25th-1969.pdf.

Download transcript: https://zenodo.org/record/6546703/files/TRANSCRIPT-Letter-from-Major-Gizaw-Gedlegeorgis-to-John-Blower.Addis-Ababa-March-25th-1969.odt.

Transcript

25th March 1969

Mr J.H.Blower

Senior Game Warden

Addis Abeba.

Dear Mr Blower,

I refer to your notes and memorandums, such as replacement of Park Warden Awash, Post Graduate Course, the landrover provided by Ford Foundation and various others.