Introduction

If photographs have a central characteristic as a document, it is the way they invade the page, whether in a newspaper or a book. They impress themselves on the written word. The proliferation of photography that marked the beginning of the twentieth century further reinforced the medium’s presence, making it a key vehicle of political debate, but also a vital way of thinking about pasts that have left behind photographic traces, even if these are scattered. Photographic material imposes an aura that can be overwhelming, presentist, and distorting. It can create an overload for those writing history, especially when they are addressing the colonial past. The first visual recordings of African social worlds via photography would long serve as a model for images of a continent that outsiders have constantly tried to decipher and that has been subjected to an “excess of signs” produced by European visual cultures (Hayes and Minkley 2019, 1–2). This phenomenon has only been reinforced by recirculations of images from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Digital technologies have exponentially increased these trajectories, assigning new meanings to colonial imagery and opening it up to new audiences. Although the images produced often bring to life and echo uneven power relations, photography is still presented in certain recent works as a unilateral expression of domination (Blanchard et al. 2018), turning the photographs that captured African social worlds in the era of colonial expansion into legacies that are sometimes burdensome, even insurmountable.

European exploratory and colonial advances in Africa in the second half of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century produced the first photographic collections of faces, landscapes, objects, monuments, and animals, at the same time as an unprecedented intensification of European expansionism was taking place on the continent. This photography was largely the work of Western photographers, at least before the 1890s. As a result, uses of photography in colonial contexts are generally considered based on a diffusionist model, or even as an incursion or an invasion (Oguibe 1996). Thought of all too often as pure technology rather than as sociotechnical process, the early days of photography are retold as the ineluctable and mechanical rise of an instrument. This is particularly true of sub-Saharan Africa, which stands in contrast to British India, China, and other spaces that, although simultaneously exposed to European and American expansionism and recorded through photography, saw local (and now well documented) appropriations of the medium that disrupt simplistic analytical frameworks (Pinney 2008; Ryzova 2015). The beginnings of photography in Africa continue to be studied unevenly, even though some essential works have been published on them over the past two decades (Zaccaria 2001; Geary and Pluskota 2003; Nimis 2005; Anderson and Aronson 2017). From Egypt, where many local studios emerged very early on, to spaces where indigenous practices of the medium developed later, a multitude of microhistories remain to be written (Morton and Newbury 2015).

The many blind spots are doubly obscured by a potentially truncated understanding of what photography has been about since its beginnings—that is, not images, but social relations inaugurated by the photographic act and enriched by circulations of the photographic object (Edwards and Hart 2004). Overlooking the variety of what photography can be risks neglecting its rich substance. To be sure, the angle of approach that has long dominated histories of photography in spaces under colonial influence, which positions photography as a generally intrusive technology that was eventually adopted by certain populations, is not worthless. But although photographic relations are often marked by a technical imbalance—itself often a reflection of colonial power relations—we must consider the possibility that they may have also been something fundamentally different.

The aim of this article is to demonstrate that one of the possible approaches to the photography of African worlds at the turn of the twentieth century involves addressing it via its absences, through the lens of the images that were refused, that were hidden, that disappeared, or that never existed for the photographic subjects. The article proposes to sketch the outlines of an implicit history by focusing on several essential phenomena that characterize the (non)production of photographic images of African social worlds in the age of colonial expansion. As Ariella Azoulay has shown, there is a need to think about “untaken photographs,” as well as all of the images that are missing, whether because they are difficult to access, impossible to reproduce for legal reasons, or simply overlooked in archival procedures (Azoulay 2010). Intended as a counterpoint, this article specifically aims to inquire into this “dark matter” surrounding the photographic act, from the (non)event of photo-taking to circulations of images. Without this, a detailed understanding of the shaping of visual cultures born at the end of the nineteenth century and the start of the twentieth is impossible. The idea here is to establish the outlines of a paradoxical history of photography by considering it not as presence but as absence.

Is making Africa the scale of focus, potentially replicating the colonial visual clichés of the late nineteenth century, a legitimate way to approach this question? There is considerable variation, for example, between the contexts of East Africa, recent research on which has made it possible to study its regions’ relationships with the arrival of photography (Palma 2005; Sohier 2020), and those of Central Africa. Among professional portraitists—local or foreign, permanently located or itinerant—amateur travellers, and European soldiers, the practice of photography in Africa at the turn of the twentieth century could take various forms, and appreciating these as a homogeneous whole seems impossible. That said, dealing with the history of photography on a large scale via local or regional studies raises just as many methodological problems as an all-encompassing, small-scale approach does. The granularity of a regional study, for example, does not always allow observation of the extent to which people and places were connected to each other when it came to photography. Many of the medium’s African pioneers were trained by missionaries and in turn trained apprentices. European settlers would sometimes take their custom to local studios (Rajaonarison 2010). A photographer born and trained in Lagos could end up working in Boma, as Herzekiah Andrew Shanu did (1858–1905; see Fall 2001, 13–16). More interwoven with its photographic histories than regional approaches suggest, the African continent offers real specificity in terms of the global history of the social uses of photography in the period under study. Unlike Asia or the Americas, where local appropriations of the medium can be observed as early as the 1840s, the arrival of photography in Africa took place in a context that was deeply impacted by European imperial and colonial expansion. This situation triggered a conjunction of factors that encouraged mechanisms of erasure. Over time, the visual overload created by an initial photographic record that was essentially external to the continent turned into an overabundance of image collections, often held in Europe and the United States. Their mass and availability have partially defined writings on the continent’s history and how they are presented visually, diverting attention from the “negative imprint of the archive” (Edwards 2014, 172) and what it makes implicit. The continental scale also enables a better visualization of the many interactions between African photography and the image cultures that circulated around the Indian Ocean or within the transatlantic visual cultures connecting Brazil, West Africa, and Europe from the nineteenth century (Schneider 2018), going beyond colonial binaries.

This article therefore proposes to adopt a broad focus as well as offering several significant case studies that have obvious local specificities. It is based on photographic and written sources dating from between 1870 and 1910. It considers photography not as a pure visual material, but as an “image/text” (Mitchell 1995, 89)—that is, as an element that is indissociable from a vast constellation of textual or oral sources (though the latter will not be directly dealt with here owing to their format). The partly unpublished examples that punctuate the article were identified during an aggregation of collections relating to the period concerned; this was conducted as part of two research projects on the history of photography (for details of the archives covered, see Foliard 2020; Foliard, Jaillant, and Schuh 2022).

This study will first deal with the key question of the disappearance of early photographic traces of Africa. An entire part of what was photographed is now either lost or in the process of becoming lost. One of the long-standing major effects of this process is that African pioneers have been absent from the global narrative of the history of photography. The second area of focus will be the question of deliberate subtraction from the gaze and the camera lens—that is, both the “contesting [of] visibility” (Behrend 2013) and the refusal to display certain photographs. We will see several scattered traces of such evasions of photography. The problem of self-censorship and the very closed way in which certain images circulated—in particular those threatening the stability of colonial narratives—will also be studied within this second approach. Finally, the article will deal with the invisibilization of the photographic act itself by studying the phenomenon of surreptitiously taken shots to explore its origins and provide a nuanced understanding of its concrete impact on the photographed populations. The article focuses in particular on photographs taken by Alex J. Braham. A district agent in Ogugu (southern Nigeria) for the Royal Niger Company at the turn of the twentieth century, his personal album contains several shots of a secret ceremony that he took without the participants’ knowledge, having hidden with his camera in a tent. This example of concealment (not of the image but of the photographic act itself) is one of the possible manifestations of the disappearances that have played a major part in forming and deforming photographic imagery of Africa. Although they are distinct at a detailed level, destructions, disappearances, invisibilities, and out-of-shot elements are not fundamentally different phenomena from a strictly methodological point of view. They comprise a negative mass that must be constantly kept in mind. These forms of subtraction are the inverse reflection of what photography is: an unstable sum of a photographed subject, a photographic act, and a gaze upon the product of this encounter.

The archive aflame

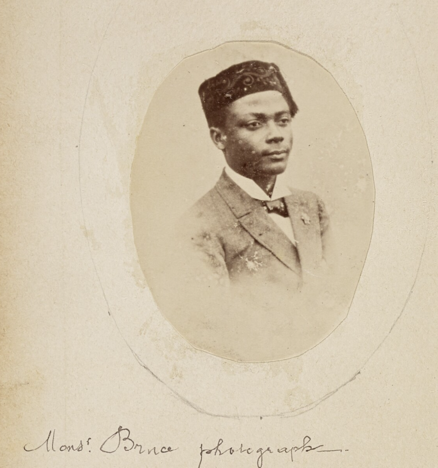

We are learning more and more about the work of African photography pioneers (Haney 2010). Recent works and exhibitions have highlighted, for instance, the role of the Accra-based Lutterodt studio.1 But there is still much to be discovered when it comes to indigenous production of photography; this is illustrated by the unexpected appearance of one “Monsr. Bruce Photographe” in the private albums of Georges Thomann, which were recently donated to the Musée du Quai Branly (fig. 1). The museum holds photographs that Thomann took between 1893 and 1925 in Africa, where he pursued a career as a colonial administrator. In particular, he founded the Sassandra cercle (administrative area) in Côte d’Ivoire. An avid photographer, he took numerous portraits of the prominent local figures he encountered. This photograph and the album it belongs to fall within the context of the establishment of the Ivorian colony, at a time when French and British imperial expansion in West Africa was shaping the colonial powers’ sovereign boundaries. The new colony neighboured Liberia, where photography spread very early on. Monsieur Bruce probably settled in Grand-Bassam in the mid-1890s. His name appears in Georges Thomann’s notebooks, where he is described as a “mulatto worker for the undersea cable”2 who photographed Thomann alongside Aya, a female captive sent “as a gift” to the administrator by a Senufo chief (Thomann, Thomann, and Wondji 1999, 147). Did Monsieur Bruce do commercial photography in addition to his main work? Did he maintain a link with neighbouring Liberia, where the African American Augustus Washington had been practising photography since the daguerreotype era (Smith 2017)? Should his name be added to the list of African photography pioneers? The case of “Monsr. Bruce” mirrors that of many other late-nineteenth-century African photographers.

Figure 1. Georges Thomann, “Monsr. Bruce photographe”

1890s, albumen print fully mounted on board, numbered in pencil, 5.5 x 7 cm. In Thomann (1880–1925*).3

Musée du Quai Branly. Inventory number: PA000589.25.

Online: https://www.quaibranly.fr/fr/explorer-les-collections/base/Work/action/show/notice/1048884-monsieur-bruce-photographe/page/1/.

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais/Thomann.

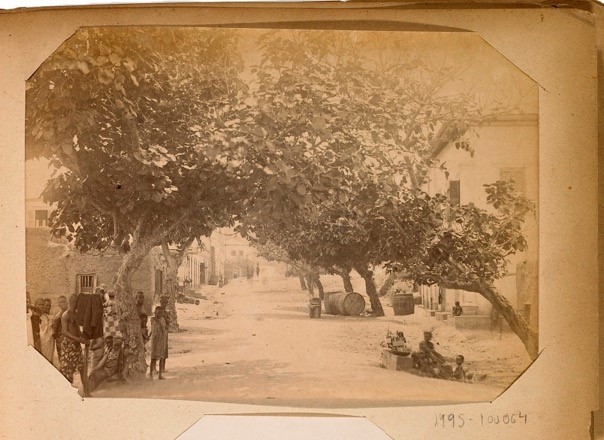

Powerful archival effects often make it difficult to reconstruct personal journeys. Local photographers are generally absent from the written documents kept by the colonial powers, and some are known only from the photographs they took and rare mentions of them here and there. The type of archival gap exemplified by Monsieur Bruce’s portrait is far from uncommon. A photograph included in an album purchased in 1995 (Ghana Photographs 1885–1910*) and held at the National Museum of African Art (Washington, DC), for example, shows a photographer with his camera on a tripod; the shot was probably taken by a local photographer who is not identified (fig. 2). In this mise en abyme, the lives of two local practitioners of the medium are therefore documented but the individuals themselves are not named. The image is taken from an anonymous album compiling photographs of present-day Ghana that were taken at the start of the twentieth century. A possible trace of indigenous itinerant photography, it reflects the dynamism of indigenous photographic production in West Africa of the kind demonstrated by the activity of Jacob Vitta’s studio in Tarkwa in the first decade of the twentieth century (Geary 2018, 20).4 The most intense phase of colonial military conquest in the 1890s seems to have given way—in official discourse at least—to what the French called “mise en valeur” and the British “development.” At the same time, stimulated by the expansion of a European and African customer base, a photography market took root, to the point where a photographer such as Francis W. Joaque was able to gain international recognition at the Exposition Universelle held in Paris in 1889 (see, for example, Joaque 1887*).

Figure 2. Anonymous, “Ashanti Rd. C.C.”

Silver print included in an album, 13.5 x 19.5 cm, approx. 1910. In Ghana Photographs (1889–1910*).

Inventory number: EEPA 1995-180064 (under the title: “Street Scene with African Photographer”)

Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives. Washington, DC: National Museum of African Art.

In the Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives: https://sova.si.edu/details/EEPA.1995-018?#ref571.

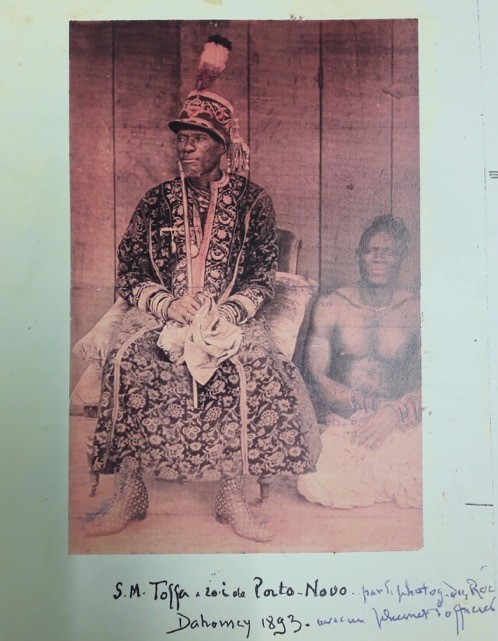

Very often, personal journeys can only be partially reconstructed. This is true of Neils Walwin Holm, who operated in Lagos and took part in the First Pan-African Conference in London in 1900 (Gbadegesin 2014). Jonathan Adagogo Green, meanwhile, is mainly known for his visual works5 (Anderson and Aronson 2017, 86–87). Knowledge of Miss Tejumade Sapara-Johnson and Miss Carrie Lumpkin, two photography pioneers who settled in Lagos in the early twentieth century, is also based on just a few sources (Gore 2015).6 Consequently, in West Africa, where studios thrived very early on as in other spaces, local uses and circulations of photography have inevitably been erased and underestimated. We also know that photography sometimes played a diplomatic role, with colonial officers and administrators being quick to give out portraits of themselves or prints commemorating a meeting or a discussion. It seems, for example, that Ahmadou Tall owned an album that was found in one of his residences by the French conquerors in the early 1890s. Toffa I, king of Porto-Novo and an ally of the French, had an official photographer, perhaps one of the Creole photographers based in the region. He could therefore exchange portraits with his European interlocutors, doing so within a complex network of exchanges of photographs (fig. 3). This tangled web of gifts and countergifts of images is unevenly documented, as are the uses and reappropriations of photography by African powers in the nineteenth century (Sohier 2020; Bruzzi 2018). The surviving traces are often those produced by European actors, creating a potential imbalance in the writing of histories of photography.

Figure 3. Anonymous, “S.M. Toffa, roi de Porto Novo, Dahomey 1893”

Silver print. In Souvenirs du Dahomey, vol. 1 (1893–1895*).

Fonds Petit. Fréjus: Centre d’histoire et d’études des troupes d’outre-mer. Inventory number: CHETOM 18 H 100.

This inexorable phenomenon of documentation loss is not limited to traces of indigenous photographic presences in African worlds. Several factors have also contributed to the disappearance of segments of the imagery produced by Western practitioners of the medium during the age of colonial expansion. What is striking to those who look closely at the colonial photographic library (Mudimbe 1988), in spite of the fact that its visual taxonomy of conquered worlds is often presented as profuse and systematic, is the flagrant loss of information. As Patricia Hayes has noted, colonial administrations’ and scientific institutions’ accumulation of tens of thousands of highly repetitive images has produced a litany of “empty photographs,” whose circularity makes them almost wearisome and plunges them into insignificance (Hayes 2019, 60–61). While this analysis is particularly true today, it may also be valid for the colonial period, in which the functional nature of certain carefully arranged but soon forgotten collections is not always apparent. Moreover, there is a considerable difference between what we understand about the realities of photographic collection through written sources and the photographic material that remains preserved in the archives. The most popular formats from the late nineteenth century, such as Lumière stereoscopic plates and projection plates, were genuinely fragile. Many of these have simply been broken or damaged. There is nothing out of the ordinary about this phenomenon. Archives are by nature incomplete, and the erosion of traces is inevitable. But in some cases, all traces of major series have been lost. For example, the Centre d’histoire et d’études des troupes d’outre-mer (Center for the History and Study of Overseas Troops), based in Fréjus, holds two boxes containing photographic plates made during the Gentil-Robillot mission to Lake Chad between 1899 and 1901 (anon. 1899*). These photographs document events that are sometimes thought of as invisible. Two plates show the survivors of the infamous Voulet-Chanoine column7. However, the numbering of the images suggests there was once a much larger set that has now been broken up or lost. The British command’s improvised—and still amateurish—control over images during the Second Boer War resulted in the accidental exposure of many Kodak films to light: the films were imprudently removed from their protective containers by overzealous censors, to the chagrin of the first generation of photojournalists (McCrachen 2015). In short, what remains of the first decades of photographic recordings of African worlds is likely only a limited part of what was originally produced.

Even more so than was the case for the photographs created by European actors at the time, local photographic production received little to no systematic heritage preservation. In many cases, the very uses of photography as an object explain how local understandings of the medium might contribute to the disappearance of images. The fate of a portrait that has been looked at, shown, and folded up many times and kept at the bottom of a pocket will inevitably be different to that of a print carefully preserved in a family album. Several examples of images/objects bear the traces of a use that doomed them to be transformed or even to disappear, as illustrated by the work of Jennifer Bajorek (2020). When they are incorporated into collections, early African photographs become “scattered across [. . .] several continents,” as John Peffer has pointed out (Peffer and Cameron 2013, 11). Although it is obvious that the management of iconographic collections varies considerably over the continent, as it does everywhere else in the world, the cost of conserving collections of old photographs also often makes it difficult for some African states to archive, digitize, and make use of them. This sometimes causes prints to deteriorate or to effectively disappear as a result of their inaccessibility (Coll et al. 2012; Nur Goni 2014). And although museums have taken a growing interest in this visual documentation in recent years, this has had adverse effects that are worth highlighting. It is overwhelmingly European and North American buyers who collect the traces of these histories of local photography in Africa. In taking these items away from the places where they were originally produced, these buyers cause them to disappear to the local public (Michelle 2012). This has equally significant consequences on the writing of histories of photography in Africa, which remains too concentrated in the hands of researchers based in Europe and North America, even if, as this article’s bibliographical references indicate, this situation is now changing rapidly.

For several years, various digital restoration initiatives and cultural events have been making it possible to counteract the effects of these successive dispersions and evaporations. The exhibition “Lights and Shadows: Insights in the Photographic Heritage of Lij Iyasu (1898–1935),” held in 2009–2010 at the National Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa to mark the centenary of Iyasu’s appointment to the throne, is one example (Sohier 2011). Another is the [Re:]Entanglements project, which explores the archives of Northcote W. Thomas, an anthropologist who went to study Nigeria and Sierra Leone between 1909 and 1915. The photographs he took within a colonial context have been exhibited in both West Africa and the United Kingdom, with the aim of submitting them to contemporary reinterpretations (Basu 2021). Instead of being left in relative invisibility within the repositories of the institutions that hold the Northcote W. Thomas archives, the images have found new lives. The recent reappearances of these photographs in the institutions of the former colonial powers or near the places depicted have inevitably prompted resignifications. As George Agbo notes about the appropriations of Thomas’s photographs in Nigeria, the inconsistent recordings of some and not others made by a representative of the British colonial power at the beginning of the twentieth century have generated contrasting effects more than a century later (Agbo 2021). While some of the old photographs in the collection have been given new life and integrated into albums to illustrate particular family histories, the descendants of groups and leaders who are absent from this archive seem to have lamented not being able to document the past in the same way. The economy of appearances and disappearances caused by photographic recording in the colonial era is therefore particularly unstable.

Erasures linked to archival effects, which are themselves reflections of unequal power structures over time, are only one of the aspects of the implicit history of the photography of African worlds that this article aims to outline. The disappearance of the images that did exist must be considered alongside the mass of refused photographs or those never taken.

Hidden images and hiding from images

As the introduction of this article reiterated, photography is a relationship. The possible histories that can be reconstructed using such a medium must include those of the photographed subjects, who may or may not have agreed to be photographed. And they cannot overlook the potential viewers of the images produced, who are ready to assign new meanings to them according to constantly changing cultural and social contexts. This second part of the article raises these two components of photographic interaction, but it does so in the negative by observing refusals to show or be shown as integral elements of histories told through and about photography (Nimis and Nur Goni 2018, 284–85).

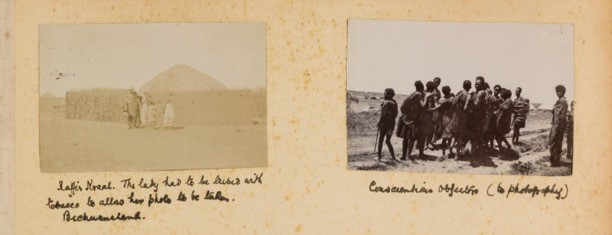

Subjects’ rejection and fear of photography are at the heart of many colonial narratives. Encouraging entire populations who were supposedly terrified by the camera to be photographed is a recurring element in narratives of exploration and conquest (Strother 2013). Situations in which photography involved constraint—for example, when prisoners posed for the camera—are also well known (Rushohora and Kurmann 2018). Sometimes less attention is paid to intermediate situations, to the scattered traces of photographic confrontations that were aborted because of the people the lens was pointed at. However, these unfinished events are traces of interactions with groups who were perfectly aware of what was going on and chose of their own volition to disappear from the frame. Striking images of this kind can be found in a regimental album compiled to commemorate the Second Boer War (fig. 4) and now held in the Wellcome Collection (London). Two shots, probably taken with a small, low-cost portable camera—one like the Kodak Brownie, which was very popular among British troops—show two aspects of the photographic negotiation that could play out during the taking of a photograph. The caption for the first reads, “The lady had to be bribed with tobacco to allow her photo to be taken,” while the caption for the photograph opposite says: “Conscientious objectors (to photography).” On the one hand, therefore, there was a step that was somewhat embarrassing and invisible to the travelling photographer: the moment when a genuine transaction predetermined the image and made it possible. On the other hand, there arose a situation that is just as common and just as absent from many albums: the photograph that people turned their back on and sabotaged. A faithful echo of these two ambivalent relationships, this unremarkable regimental album highlights the possible extent of the many small resistances to being recorded that very often thwarted the encyclopaedic desires of European photographers in African worlds. Although the violence of war certainly had a decisive impact on this specific photographic relationship, societies’ openness to engaging in the practice of photography should not be exaggerated, as Hlonipha Mokoena has demonstrated in the case of South Africa (Mokoena 2013).

Figure 4. Anonymous, “Kaffir Kraal. The lady had to be bribed with tobacco to allow her photo to be taken. Bechuanaland” and “Conscientious objectors (to photography).”

Album of photographs of the 14th Brigade (Lincoln Regiment) Field Hospital in the Boer War (1899–1901*), 17. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/j4hs98ha/items?canvas=16 [archive].

London: Wellcome Collection, inventory number: RAMC/1612.

Online: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/j4hs98ha.

CC BY-NC 4.0

Is it possible to imagine a cartography of these rejections and evasive attitudes? Between Morocco, where distrust of photography was often clearly expressed at the time, and the “Yoruba experience,” the contrasts are striking, though their details are difficult to grasp based on the available documentation (Perrier 2021; Nimis 2005). According to the context, these forms of very conscious refusal may have taken on considerable proportions, stimulating the inclusion of certain groups in the photographic archives and the virtual absence of others. This has consequences on contemporary reappropriations of the visual heritage of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Werner 2002). When examining this photographic documentation, it is equally important to consider the out-of-frame space where people could always take refuge, to think about the viewers gathered behind the carefully positioned camera, and to reflect more broadly on the photographic act and its potential audience. This audience may have sometimes disappeared intentionally, but it too played a role in what unfolded around the image.

Local populations’ rejection of photography may also have stemmed from their not attributing any evidential value to it, simply because it may not have served a functional purpose in their eyes. One of the strongest stereotypes around photography is that photographs are naturally readable—that is, that even in the earliest years of its history they were a universally understandable document. This promise seems to be rooted in its invention in Europe. Immediate, easy, democratic: from very early on, the photographic image was thought of as a synecdoche of industrial modernity. But the world had to learn to read these images over the decades. In the twenty-first century, their ubiquity means they pose little or no difficulty, but there was nothing obvious about photographs for many human beings in the late nineteenth century. They had to learn to read them. In some cases, the medium’s supposed powers were therefore denied by indigenous viewers who were indifferent or unconcerned about including it in their discussions. One of the most striking cases of this denial of photography is the reaction of the family of Bhambatha kaMancinza, a Zulu chief who was killed by colonial troops under the orders of British imperial officers in June 1906 during the Battle of the Mome Gorge, putting a bloody end to the rebellion led in his name. After he was decapitated, his head was displayed and photographed to prove to the local populations that he was dead. Yet, part of his family, denying the photographic evidence, later claimed that Bhambatha was in fact alive and on the run (Binns 1968, 279).

In addition to images that people hid from, a discussion on photography as absence must also include images that were hidden. This is particularly the case for certain images captured during the most intense phase of colonial expansion, which took place at a time when photographic equipment was becoming relatively accessible, including for colonial noncommissioned officers. A considerable mass of amateur images was thus produced from the 1890s. The regimes of memory characterizing the professional, familial, and friendship circles of individuals involved in colonization therefore gradually afforded a significant role to photography as a tool for crystallizing narratives and experiences. While a large majority of these shots are highly repetitive and coded, some of them can give unprecedented visibility to aspects of the colonial experience that participants may have wanted to hide or keep for a restricted network of viewers. Certain albums that were never intended for public circulation document the existence of female “captives” who were taken during conquest and served French officers. Their suggestive captions make it clear that some of these captives were also intimate companions. One example is a very young woman called Fatimata, nicknamed “Mlle Bonéné”8 in the handwritten captions; several portraits (1894) of her can be found in the private collection of a French noncommissioned officer who was sent to French Sudan in the mid-1890s (Abbat 1894–1896*, photographs 119 and 120). Few individuals showed photographs of their mixed-race children in mainland France or acknowledged their existence. The aforementioned Georges Thomann was one exception, however. The colonial administrator kept several photographic portraits of his daughter Louise, whose existence he did not hide from his family in France. Self-censorship and discretion also led to some people keeping certain other photographs—potentially even more scandalous ones—without allowing too many people to view them. In a reflection of colonial situations where relationships with living and dead bodies were determined by powerful racial dynamics, the camera was sometimes used as a tool of “extra-lethal” violence, to use the concept developed by Lee Ann Fujii (2013). Some images—trophy photographs and photographed executions during which the presence of the camera had to have been obvious for the condemned—were clearly intentional acts of transgression, tools of a staged performance that were additional to the physical violence in the strict sense. They only made it through the filter of strict self-censorship in situations of intense colonial hubris.

The photographer disappears: On stolen images

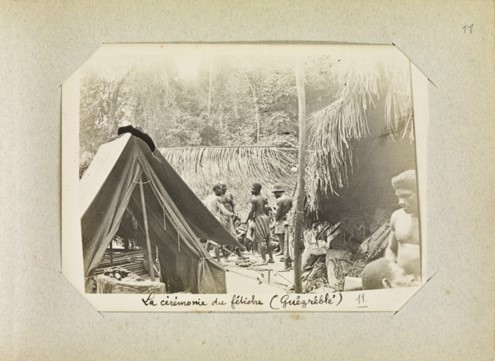

A further look at the albums of Georges Thomann reveals a series of photographs documenting a ceremony he captured in 1902 during his mission to Séguéla in Côte d’Ivoire (Thomann 1903a). Upon closer observation, these photographs appear to have been taken without the participants’ knowledge, since none of them seems to be aware of the camera’s presence (fig. 5). Although it is difficult to ascertain whether these images were surreptitiously taken—as passing Europeans were allowed at this ceremony—a local misunderstanding about what a camera was may have helped Thomann out. This photograph and others were used as illustrations for an article that Thomann had written for the Journal des Voyages in 1903 (Thomann 1903b, 352). Whatever the circumstances in which the photos may have been taken, their recirculation as photogravures is part of a recurring pattern of the time that consisted in unveiling supposedly exotic and mysterious religious ceremonies. Far from being specific to Africa, this was a generalized phenomenon. One example here is the two photographs taken by George Wharton James that show, in two stages, the reaction of the members of Governor Eusebio’s team in Acoma (New Mexico); tired of years of dealing with intrusive photographers drawn to the region in the hope of photographing ceremonies such as the snake dance, they refused to be photographed (Barthe 2019, 26–27).

Figure 5. Georges Thomann (1872–1943), “La cérémonie du fétiche (Guézréblé)”

Date: February 3, 1902. Aristotype print, 12.5 x 17.5 cm. In Thomann (1902*).

Musée du Quai Branly. Inventory number: PA000593.11

Online: https://www.quaibranly.fr/fr/explorer-les-collections/base/Work/action/show/notice/1049965-la-ceremonie-du-fetiche-guezreble.

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais/Thomann.

To better grasp the possible meanings of these photographic incursions, I propose to revisit the archives of Alex J. Braham. Examined by Andrew Apter a few years ago, these are held at the Bodleian Library in Oxford (Apter 2002). Braham joined the Royal Niger Company in 1898. A district agent in Ogugu, he owned and regularly used a camera. An explorer and amateur ethnographer in his spare time, he produced his own personal visual archive, a self-archive typical of colonial agents’ practices at a time when the British were consolidating their power in the region. His archive takes the form of an album of several dozen images and is titled A Pictorial Episode in the Life of Alex J. Braham 1898–1902, with two contrasts (Braham ca. 1902*). Long explanatory comments accompany each photograph. When, during his travels, Braham became aware that a secret ceremony was set to be held in an Igbo village, he did not think twice about setting up his camera inside a tent and aiming the lens through an opening in the fabric. This ethnographic concealment resembled espionage. Hidden, and aided by an assistant trained in handling negative plates, Braham surreptitiously took several images over the space of a few minutes. Pleased with his success, he wrote a detailed handwritten account about it directly in his album, under the furtive photographs. As Apter stresses, this type of example represents the epitome of photographic violence and echoes the practices of the Royal Niger Company, which at the time was destroying some of the sacred objects that came into its possession. Here, desecration and photographic capture are in line with colonial practices involving the collection, relocation, and even annihilation of indigenous artefacts.

These images embody the “optical violence of colonial appropriation” (Apter 2002, 566), but what does this tell us about the power relations at work? Was this colonial visual discourse as effective as the spectacular photographic trickery devised by Braham might lead us to believe? For ultimately, the central question is that of who saw these photographs. Affixed into Braham’s album, they did not circulate beyond a very limited circle. The populations he photographed never saw the images or learned of their existence. In emphasizing this point, we do not wish to underplay how invasive and morally unacceptable it is to take any image surreptitiously. Rather, we seek to stress the importance of observing local circulations of colonial photographs. Receptacles of the imaginaries of Westerners involved in European expansionism, such photographs were not necessarily always vehicles for their power on the ground. In Braham’s case, they remained hidden from a potential Igbo audience, just like his camera. In this instance, they did not disappear; they simply did not appear at all. Using photography as a source on African worlds also implies questioning the reality of these local circulations, which are very complex to evaluate in the case of more distant periods. The discourses conveyed and nurtured by photographs from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries sometimes remained just that: cultural constructions on explored spaces and colonized populations rather than concrete instruments of domination.

Conclusion

The photographic material produced during the first decades of the medium in African worlds is rich in terms of both presences and absences, with the latter surely being more revealing than the former. Trying to understand the one without the other would present the risk of oversignifying these objects that are “entangled” in a multitude of contexts and uses (Edwards 2006). Only a contrapuntal reading can draw out their true documentary richness. However, as attentive as this deciphering may be, it will inevitably be rewritten, set aside, and transformed owing to how inherently unstable visual materials are. As several examples of circulations of photographs during the colonial period show, visual media can become one of the essential vehicles for constantly evolving memory and historical constructions. This is particularly true of the increasing circulation of digitized old photographs, which have sometimes become flashpoints for reconfiguring the past on social networks. This shift heralds another potential disappearance whose importance should not be overlooked: the tangible relationship between individuals and the pieces of paper long known as “photographs” is becoming obsolete. The absences from photographic archives that have been determined by powerful mechanisms can nevertheless become full objects of study rather than being deemed losses of meaning if dynamic research on the medium is undertaken on a collective, collaborative, and transnational basis.