Introduction

In 2009, the Nigerian security forces killed Mohammed Yusuf, the leader of the sect popularly known as Boko Haram based in north-eastern Nigeria. This extra-judicial killing and its spiralling effect in mobilising Mohammed Yusuf’s acolytes has, since then, extended the popularity of the sect beyond its initial base in the city of Maiduguri.1 Between 2010 and early 2016, large swathes of land in the northeast of Nigeria were ceded to the control of Boko Haram members. This went together with frequent attacks in urban centres until 2013 when the security forces, in collaboration with the Civilian Joint Task Force, dislodged most known Boko Haram cells within many cities and towns, forcing members of the sect to emigrate en masse to hinterland areas in the vicinity of the Gwoza Hills, Mandara mountains, and the Lake Chad islands (Mahmood and Ani 2018). In addition, the use of asymmetrical warfare tactics against civilian and non-civilian targets (using women and girls as suicide bombers) and frequent militaristic assaults in failed attempts to gain entry into the city of Maiduguri influenced the sociological management of space and securitisation in the Borno and Yobe States. After 2013, the sect began to launch coordinated attacks, with armed members attempting to gain control of these areas. At the time of publication of this article, the capture of these Boko Haram-controlled territories by the Nigerian army was almost completed, with many Boko Haram factions now hiding out in the Lake Chad axis (Seignobos 2016). However, these former Boko Haram-controlled zones along with other parts of north-eastern Nigeria are still prone to occasional Boko Haram attacks. Some of these zones have been converted to buffer zones by the Nigerian security forces, rendering them inaccessible to most civilians. The transformation of Boko Haram from being an extremist sect to an armed movement has had far-reaching effects on the biographical narrative of the Nigerian state. The current leader of a faction of the sect, Abubakar Shekau, is considered to be one of the most wanted terrorists in the world (Brigaglia 2014). The Nigerian government has increased its security budget exponentially since Boko Haram’s insurgency began in 2011 (Onuoha, Nwangwu and Ugwueze 2020), in a bid to squash what was initially considered an insignificant threat. It has also propelled this hitherto fringe movement into the international discourse on terror and collective violence.

In this context, a steadily growing demand has arisen for data across different fields and by various institutions. It has led to a growing field of study on all things concerning Boko Haram and resulted in the production of literature attempting to contribute to the production of knowledge on Boko Haram, with threads linking to various academic disciplines or fields of expertise. The various approaches used to analyse the emergence of Boko Haram and its re-emergence as a violent movement can be credited with the creation of multi-dimensional lenses, themselves commensurate with the multi-faceted aspects of the sect itself. This has given birth to scholarship situated in Islamic studies, international relations theory, gender studies, social movement theory, history, anthropology, and security studies, among others. However, despite the sect’s insurgency lasting more than a decade at present, and the continuous production of writings of different forms on various topics relating to Boko Haram, there is still arguably so much that remains unknown about its past all the way to its present. More profoundly, in spite of these new perspectives, one major problem remains, which affects the production of knowledge about this sect: first-hand anthropological data in north-eastern Nigeria remains difficult to collect for most researchers on the region. This is primarily due to the climate of fear and insecurity engendered by more than a decade of insurgency by Boko Haram fighters in the region and its environs. It is within this context that conjectural analyses, derivative data, and unfounded and conspiracy theories emerged and fuelled a large majority of the literature produced on north-eastern Nigeria and the Boko Haram insurgency, in particular.2 However, as this article illustrates, empirical data is invaluable to unearthing a more nuanced understanding of the insurgency in north-eastern Nigeria. In order to achieve this, though, some degree of anthropological research is required. The article argues, based on my own ethnographic fieldwork experience and that of other researchers, that there are methods of navigating around the field, as the human element is of primary importance in collating narratives on the impact of Boko Haram’s insurgency in north-eastern Nigeria.

This article attempts to study the economy of information on the sect itself. It draws upon ethnographic data collected during fieldwork in northern Nigeria, and north-eastern Nigeria in particular, to make the argument that the absence of a wider stream of ethnographic data on Boko Haram has encouraged the use of derivative data, and in some cases none at all, in the study of the sect. After analysing how most researchers have conducted research on Boko Haram (section 1), I will reflect on the constraints in which I, myself, conducted fieldwork (section 2). I will thus show how the use of selected material and field notes can shed light on the sect and its dynamics. For the purpose of underscoring the centrality of ethnographic data to better understand Boko Haram, I have selected two elements from my fieldwork material: first, a letter purported to have been distributed in Kano by Boko Haram prior to the beginning of my research in the region in 2013, which I have in my possession and have translated from Hausa into English. Through this example, I argue that the ethnography of documents produced by Boko Haram can help researchers to limit what I call the “erosion” of sources in the case of the sect (section 3). Secondly, I present a condensed summary of the fieldwork interviews I conducted at Kuje Minimum Security Prison with convicted Boko Haram members and with some workers employed under a European Union-funded deradicalisation programme set-up for the convicts. In a context of unavailability of prime sources of information, researchers can use information provided by former members or sympathizers of the sect (section 4). While advocating for caution where ethical issues are concerned (section 5), I conclude that the anthropological sources of data have to be emphasised in order to fill the glaring gaps responsible for the economy of data scarcity on the study of Boko Haram.

Navigating the scarcity of ethnographic data on Boko Haram: a literature review

The scholarship on Boko Haram is characterised by an impressive number of publications.3 Yet, only a small minority of those publications is based on original first-hand data. What are the factors responsible for the scarcity of data in the field of study on Boko Haram? How have scholars attempted to navigate the challenges around data collection? The field of study on Boko Haram currently finds itself in a difficult position due to two major informational gaps: the organisational structure of the sect, and the attitude of the Nigerian state.

On the one hand, and even before July 2009, Boko Haram already had a peculiar organisational structure, mostly due to its insular religious ideology of separation from “unbelievers” (Murtada 2013). This has helped to make the sect exclusive and impenetrable, with few outsiders having limited access to its goings-on. In addition to this, whereas before it was considered a marginal sect with its hub based in an urban centre (i.e. Maiduguri), Boko Haram’s post-July 2009 factionalisation and migration has seen the sect’s members gradually desert urban areas in order to occupy most recently geographically peripheral areas on the banks of the Lake Chad and the Lake Chad islands. This has made access to Boko Haram and data on the sect even more difficult, due to the notoriously inaccessible nature of the Lake Chad zone, a phenomenon that predates the emergence of Boko Haram. As Marielle Debos (2016) pointed out, the Lake Chad axis has a historical reputation as a haven for rebels who were hostile to the former Chadian President Hissène Habré in the early 1980s.

Moreover, the Nigerian government’s state policy regarding the Boko Haram insurgency has arguably proven to be counterproductive in bringing about its end. This is largely due to the harassment and detention of individuals suspected of being Boko Haram sympathisers, including individuals allegedly pressured by the government to act as intermediaries with the leadership of the sect. Contrary to the state narratives, journalistic reports in the past have alluded to negotiations between Boko Haram and the Nigerian government. The absence of publicly accessible evidence, however, has made these reports difficult to substantiate. Negotiations and agreements between Boko Haram and the Nigerian state hardly ever feature in analyses of the conflict between the two sides. Yet, this is a factor that has shaped the trajectory of important episodes in the timeline of the conflict between the Nigerian state and the sect. It is, however, necessary to chronicle these “unrecorded” engagements in order to avoid a jaundiced narrative of the insurgency. For example, Boko Haram fighters adopted the method of abduction in north-eastern Nigeria as leverage in negotiation deals for the release of their fighters and relatives in the custody of the state, which could explain the Chibok girls kidnapping in April 2014.

During the July 2009 skirmish between Boko Haram and security forces in Maiduguri, the first erosion of the most direct links to Boko Haram began, with the extra-judicial killing of Mohammed Yusuf and some of his acolytes. The next phase of this erosion came in the aftermath of these killings, beginning with the arrest of many Boko Haram identified by the security forces. During this period, several members were also killed in various attempts by the security forces to apprehend them. The indiscriminate arrest and detention of relatives of Boko Haram members followed suit. Many of these relatives—some of them being women and children—were allegedly detained in secret locations without trial. Among them were one of Abubakar Shekau’s wives and their children, and one of Mohammed Yusuf’s widows.4 Much of the protracted negotiations between factions of Boko Haram and the Nigerian government from 2011 to 2015 were centred on the sect’s demand for the release of their detained spouses and children. The subsequent release of Abubakar Shekau’s wife, Hassana Yakubu, along with her children, and of other family members of Boko Haram, can be attributed to the Nigerian government’s acquiescence to the sect’s conditionality, or the desire by the government to resolve the ethical lacuna connected to the detention of relatives of Boko Haram fighters, according to those privy to the negotiations. Regardless of the rationale behind the government’s actions, the as-yet unrecorded discussions between the leadership of the Boko Haram sect and the Nigerian government is an indicator of the multiple layers of the insurgency that are still in need of uncovering.

Because of these gaps, the field of study on Boko Haram currently finds itself in a paradox. More than a decade after the sect transformed to an armed movement, the insurgency continues. However, there is still so much that appears to be unknown about various strands of the sect and its biographical narrative. At the same time, the appeal of the topic has led to an overproduction of academic and non-academic or grey literature to satisfy the high demand for more information. Yet, only an infinitesimal amount is based on actual first-hand data, which adds to the recycling of information and further obscuring of the sect and its workings. Most publications hardly bring any actual critical evidence nor diligently explain their methodology that could help verify how they reach their conclusions.

Despite this methodological opaqueness, insight on how to navigate issues of access and accessibility can be gleaned from the works of scholars whose research has proven seminal in this field. These researchers have developed their own methodological mix while facing constraints. Political scientist Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos visited Maiduguri as well as Kano, Zaria, and Abuja several times after July 2009 to conduct interviews. He, however, noted that he was unable to travel to Maiduguri at all between 2013 and 2014, after the closure of the Maiduguri International airport by the military. Although he makes no mention of accessibility difficulties in his research, this can be implied from his writings. Pérouse de Montclos had more success in Niger, where he notes that he was able to interview security officers in Diffa and also conduct interviews with presumed members of Boko Haram in the Koutoukalé and Kollo prisons, at the beginning of 2015 (Pérouse de Montclos 2016, 879). Another case is Adam Higazi’s anthropological study on Boko Haram’s mobilisation in north-eastern Nigeria. His work is arguably the first piece of research that focuses on the Gwoza region and population within the context of Boko Haram’s insurgency. Higazi’s fieldwork-reliant study in the hinterland of north-eastern Nigeria relevantly confirms the establishment of Boko Haram’s bases within this borderland region, particularly within the Muslim section of the multi-ethnic Gwoza Hills population. It also helps to confound conspiracy theories regarding the supposed seamless acclimatising of transplants from urban areas such as Maiduguri to this rural terrain (Higazi 2015, 346). Higazi was able to accomplish this detailed study of the Gwoza population by having the foresight to travel to Gwoza before the mass migration of Boko Haram members from Maiduguri and other hubs to the north-eastern hinterlands.

Predicting the significance that the killing of several key members of Boko Haram would have on the scarcity of data on the sect, Murray Last, who wrote in 2009, confesses himself to relying on daily or weekly newspapers like Daily Trust, Leadership, Weekly Trust, Amana and local radios. Information he extracted via these sources was supplemented and crossed with information from various other sources in different cities across northern Nigeria (Last 2009, 11). Christian Seignobos, exploring the presence of Boko Haram in the Lake Chad axis in 2015, reveals a similar method of data collection as he relied on media reports and the relaying of information from interviewees and informants living in the Lake Chad axis. He, then, counterbalanced the information received with specific historical situations to bring context to the data (Seignobos 2015, 90). According to political scientist Hilary Matfess, apart from being a relatively new phenomenon, a reason why Boko Haram has not yet enjoyed the sort of analysis that other insurgencies, social movements, and terrorist groups have had is due to paucity of access. She posits that the reliance on second-hand accounts and newspaper reporting in much of the scholarship on the sect’s insurgency in north-eastern Nigeria may decrease if the Nigerian military securitize the region, therefore making fieldwork more feasible (Matfess 2017, 17).

Researching Boko Haram: constraints of conducting ethnographic fieldwork

As a doctoral candidate, I conducted fieldwork across different cities in northern Nigeria, between October 2013 and December 2015, for a period lasting a total of six months. I faced two major issues: security fears, and reluctance of the inhabitants to share information with me.

Before I began my fieldwork research in northern Nigeria, I had actually not considered the possibility of travelling to north-eastern Nigeria because bomb attacks were on-going as well as gunfights between the government forces and the insurgents. Boko Haram cells in Yobe and Borno were also frequent at the time. While the situation was the same in Kano, the city was in my estimation relatively safer than the former two states. However, the gradual realisation, after three months in Kano, that beyond controlled interviews, there was very little to dredge up by way of gaining direct and relatively unfettered access to reliable sources of information on the sect influenced my decision to shift base to Maiduguri, the capital of Borno. By the time I arrived in Maiduguri in July 2014, I came to the conclusion that the paucity of access to first-hand inside knowledge on Boko Haram was not exclusive to regions beyond the northeast, such as Kano, but had affected the north-eastern region most of all. The security situation was arguably worse in Borno than in any other part of the northern region. There was no exact formula for accurately predicting the time range or intended targets of Boko Haram attacks, which meant that residents had to avoid public spaces which attracted crowds. This was not so much the case in Maiduguri due to the rare occurrence of Boko Haram attacks on the city itself over the last five years. This has allowed for a semblance of normalcy to return to the city.

I arrived in Maiduguri on a Saturday in July 2014, three days after a bomb planted by Boko Haram at the Maiduguri Monday market killed scores of people.5 When I went to this market seven days after, it had been re-opened for business and was heavily re-populated with traders and buyers. As such, while there had been a heavy securitisation and militarisation of public spaces in most of the north-eastern urban centres and especially in Maiduguri, there was no uniformity in the ways in which residents reacted between July 2014 and December 2015, though the government-imposed curfew on activities in Borno achieved this to some extent. However, as a researcher and visitor to the region, I was primarily concerned with the issues of mobility and security as they could have limiting effects on my work. I needed to travel around to source for data while at the same time reducing the possibility of coming to harm as much as possible.

The first impediment I encountered regarding mobility manifested itself in the choice of commute to Maiduguri. President Goodluck Jonathan had ordered the closure of the Maiduguri international airport in December 2013 to commercial flights6, leaving access into the state by road the only option for civilians7. This was where, for me, the issues of mobility and security intersected as I got access to reports informing about coordinated attacks by Boko Haram on certain highway routes targeting commercial vehicles transporting passengers within and around the northeast. Despite this travel difficulty, I boarded one of the buses travelling to Maiduguri via Damaturu at the Kano terminus early in the morning in order to avoid being on the road by evening, which would have increased the probability of being waylaid by Boko Haram. This mode of transport did, however, prove to be advantageous to some degree, as my first encounter with the Civilian JTF vigilante group8—which also involved watching them in operation—occurred at a road-block between Damaturu and a town on the outskirts of Maiduguri.

I encountered another constraint that hampered access to data: the pervading fear among local residents of both the government security forces and Boko Haram. Initially, during the early phase of my fieldwork in Kano, I was attempting to study Boko Haram mobilisation techniques and reasons for local support in some of the wards where the existence of local cells had been confirmed (Hotoro and Wudil, outside the city, being examples). Although I had always intended to interview imprisoned Boko Haram members, I also wanted to have as broad a category of interviewees as possible. This ethnographic naiveté with which I approached my study quickly dissipated, as I discovered that there was a strong reluctance by local residents to use the “Boko Haram” title, much less engaging unfamiliar persons in conversation about any themes related to the sect. The fear of the police and Boko Haram was a major deterrent towards sharing pertinent materials. Understandably, with respect to the modus operandi of Boko Haram, local residents did not want to fall on the wrong side of the sect by being perceived as colluding with security forces to identify their members. This was more so due to the fact that it was impossible to identify those employed to spy and relay information back to Boko Haram within different wards.

The lack of easy access to insiders or those with first-hand knowledge of the goings-on within Boko Haram also makes it more difficult to sourcing ethnographic data on the sect. Achieving this, or trying to do so, can put researchers at risk. It is also worth noting that the individuals who have been successfully engaged as negotiators between the sect and the Nigerian government have thus far been sanctioned by the top cadres of Boko Haram. The few non-members who have continued to have access to Boko Haram are individuals who have adopted an ostensibly neutral position in refusing to outrightly condemn Boko Haram in its entirety or who have a long-running history of engagement with the sect that precedes 2009. Mohammed Yusuf’s use of his Kanuri kinship (coupled with the heavy emphasis placed on expansionist proselytisation by his then religious organisation, the Izala9) to cultivate Boko Haram’s network links is also pertinent in understanding the successful propagation of his religious ideology in the northeast and also how he extended it to neighbouring regions in Cameroon, Niger and Chad by also making use of the expansive preaching network of the Izala movement.10 Consequently, these ethnic and religious markers have been used to accentuate the otherness of non-indigenous researchers seeking to access communities in north-eastern Nigeria for their fieldwork.

Moreover, the scorched earth approach adopted by the Nigerian security forces against Boko Haram in the aftermath of the sect’s 2009 revolt resulted in the arrest and imprisonment of several non-combatants alleged to have had some connection, whether directly or indirectly, to Boko Haram. In more extreme cases, there have been allegations raised against the army by Boko Haram, who accused soldiers of killing unarmed Boko Haram “emissaries,” thus making it less of an appealing incentive for those with first-hand knowledge of Boko Haram to make themselves known.11 By destroying the places of worship and residences of alleged Boko Haram members, potential sources through which to retrieve data on the sect have been wiped out. Also, this has reflexively led to the dispersion of potential sources of human data. This is because many of the casualties of this blanket policy which mostly affected those residing at Railway Quarters in Maiduguri—where Mohammed Yusuf’s core following were mobilised from in the early years of Boko Haram’s formation—were not themselves members of the sect but their relatives to acquaintances, or in some cases had attended the popular sermons of the sect’s clerics.12

There is also an absence of precedent regarding information-sharing between the security agencies and the Nigerian public, which hampered the verification of data. Thus, the government has displayed its ineptitude in the area of intelligence-gathering. For example, in relation to the abduction of around 234 school girls from Chibok in Borno State, the media arm of the Nigerian army delayed the confirmation of the incident only because the government itself had not immediately verified the veracity of the reports. According to former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo who conducted a fact-finding mission in Borno in the aftermath of the Chibok tragedy, it was discovered from the local residents that the abduction of the school girls was an afterthought by Boko Haram members. As has now become the norm since they began to occupy towns and villages outside Maiduguri, Boko Haram raided Chibok in search of foodstuff and other materials to replenish the dwindling supplies at their neighbouring base (Habila 2016). However, on leaving the village, they met with school girls who had stayed overnight at the local secondary school and decided to abduct them.13 The Borno State government also supported this narrative, with Governor Kashim Shettima placing the blame on the federal government for the delay in taking action to rescue the abductees after he had directly informed President Goodluck Jonathan of the incident.14 This example highlights the disjuncture in the governmental approach to information gathering.

Conversely, where the government has been able to access certain information, it has in some cases been accused of disinformation as well as of being economical with the information released to the Nigerian public. The bulk of these accusations relate to the control on information about the military campaign against Boko Haram by the Nigerian army. The Nigerian army’s media arm has been accused in some quarters of “bending the facts” of its current campaign against Boko Haram in the north-eastern region in a bid to either conceal its tactical ineptitude or to avoid losing the “media war” to the sect. This has culminated in episodes in which the army has made a report only to have it be contradicted by another report. This insistence on controlling the media narrative, whenever Boko Haram’s activities are concerned, makes the army an unreliable source of information. In 2015, a member of the Air Force arm of the military from Adamawa was reportedly captured and killed by Boko Haram fighters while on active duty in the northeast. This event was reported by a Nigerian news medium but the army denied it in a statement it released after the breaking of the news. I interviewed a relative of the deceased soldier who confirmed that the military refused to release the news of the death of their kin for months, despite knowing he was dead from the evidence which had been released (his military uniform was shown in a video taken by Boko Haram combatants after they had downed his fighter jet). The interlocutor even denied that their kin was a soldier when images showing him were released by Boko Haram. The army, however, later sent an envoy to confirm the death of the soldier and condole with his family.15

As I gradually became aware of these constraints on conducting research on Boko Haram, I opted for different strategies in order to gather ethnographic data. First, difficulties of this sort, which I encountered, helped me better understand the utility of relying on a “gate-keeper” when conducting ethnographic research, particularly one which requires entry into a guest culture or community. In the case of Boko Haram, the mode of delivery of warning letters to communities and in some cases to individuals (see section 2) added credence to my hypothesis that these tasks could only have been achieved with stealth by those familiar with the local geography. Also, from my study of the tone assumed by Boko Haram in missives delivered within local communities both in Kano and Borno, which I collected on my fieldwork travels, I perceived what was a deliberate attempt by the respective authors of these notes to convey to their intended audiences their familiarity with them and ease of access to them if they disobeyed their injunctions.

Moreover, I recruited and worked together with a research assistant who was familiar with the area where I conducted fieldwork and also doubled as my Hausa translator. I was able to use him as a liaison to conduct interviews with local residents. As someone indigenous to Kano and with a wide network of acquaintances, my assistant was able to draw from his repertoire of information to direct me, telling me where to go and search the data I needed. He also acted as a safety barometer, of sorts, adjudging which locations we could travel to and the ones in which the level of risk outweighed any potential research value to be gained (this was a period of heavy skirmishes between government forces and Boko Haram fighters who the former were trying to flush out of wards within Kano and the outskirts).16 The exact role of my research assistant was to accompany me to meet potential interviewees and help with translating from English to Hausa and vice versa during my interviews with non-English speakers.17

Finally, I always made sure to let prospective informants know that I would only be using my notebook and pen and that their names would not be appearing in any of my public writings. In such, I borrowed from Wood’s template which she used during her fieldwork in El Salvador: she was disguising her notes and refusing to record any names or voices in order to ensure the protection of the identities of the subjects of her study (Wood 2006, 381).

In total, I conducted a 6-month fieldwork in north-eastern Nigeria. Interviews were conducted in fieldwork sites located in Kano, Abuja, and Maiduguri, respectively. I resided in Kano from October to December 2013. There, I conducted semi-structured interviews with prison inmates (some of whom were suspected by the authorities of having been complicit in Boko Haram-related acts of violence) at the Goron Dutse Maximum Security Prison. I also conducted semi-structured interviews with state government officials, particularly officials of the Kano State Hisbah. I resided in Maiduguri from June to August 2014 and also spent the month of December 2015 there. During my time in the city, I conducted semi-structured interviews with residents of Railway Terminus Quarters (Shehuri North ward), individuals who were acquainted with Mohammed Yusuf during the years he spent in Maiduguri establishing Boko Haram, relatives of deceased Boko Haram members, and self-confessed former members of the sect. In December 2015, I conducted interviews with some members of the team employed under the European Union-funded pioneer deradicalisation programme designed to rehabilitate convicted Boko Haram members imprisoned in Maiduguri and Abuja. In the same month, I conducted semi-structured interviews with Boko Haram convicts imprisoned at Kuje Medium Security Prison.

An ethnography of Boko Haram documents

One of the issues researchers on Boko Haram face is the “erosion” of sources, by which I mean the inability to access previous human sources and sites for collecting first-hand data, particularly because of population displacement. For example, during the July 2009 skirmish between sect members and security forces in Maiduguri, the first erosion of the most direct links to Boko Haram began, with the killing of Mohammed Yusuf and his acolytes. The next phase of this erosion came about in the aftermath of the July killings, beginning with the arrest of many Boko Haram members identified by the security forces. During this period, several members were also killed in various attempts by the security forces to apprehend them. The indiscriminate arrest and detention of relatives of Boko Haram members followed suit. Many of these relatives, some of whom were women and children, were allegedly detained in secret locations without trial, among whom were one of Abubakar Shekau’s wives and their children,18 and one of Mohammed Yusuf’s widows. Furthermore, in the course of traversing Maiduguri in 2014 to locate relatives of Boko Haram members or those who might have been morally supportive of the sect at a point, I discovered that those who had been identified by other local residents as being previously frequent attendees of Boko Haram mosques, being members of the sect or in certain cases having been close relations of known Boko Haram members faced stigmatisation within their locales. Many among them emigrated out of Borno. Those who remained, some of whom I encountered, were hostile to having their past affiliation with Boko Haram recalled.19

To counterbalance the gradual disappearance or inaccessibility of human sources and also retrace Boko Haram’s emergence and activities, I turned to material artefacts produced by the sect. I had also grown frustrated with the recycling of mostly-conjectural analyses, whereas I used and kept references to videos of sermons by Boko Haram clerics, letters distributed by the sect’s members, and a book by Mohammed Yusuf titled Hādhihi ‘Aqīdatunā wa-Manhaj Da‘watunā.20 My attempt at engaging with actors familiar with Boko Haram’s ideology was thus aimed to gain access to written materials by the sect, which in my opinion offer insight into Boko Haram’s collective and ideological self-perception.

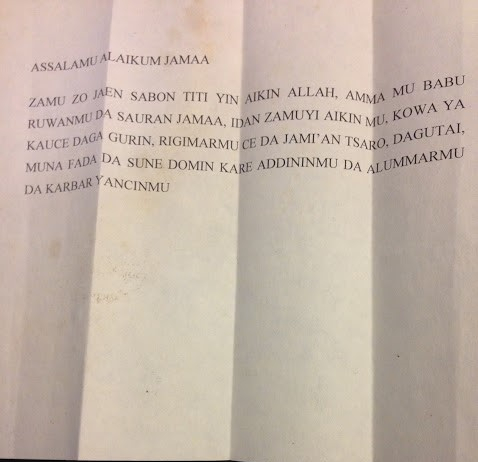

A letter purportedly distributed by Boko Haram members specifically to residents of a particular locale in Kano

Translation (from Hausa): “Peace be upon you, people. We will be coming to Sabon Titin (New Street), Jaen (Sharada Local Government Area), to execute Allah’s work, but we have no business with the rest of the people. When we are going about our work, everyone should avoid the place. Our quarrel is with the security forces. We are fighting with them to protect our religion and our business, and to claim our right.”

Copy in author’s possession.

A number of narratives have emerged from different parts of northern Nigeria over the years corroborating claims that Boko Haram was using locally-distributed letters to pass across messages to specific demographics.21 The image above is a letter purported to have been composed by Boko Haram. Printed on a white sheet of paper, written in capital letters and unsigned, it was distributed to residents in the Sharada ward of Kano prior to an attack between 2011 and 2012. The letter was given to me via my research assistant at the time, a resident of the locale where the letter was purported to have been distributed. The residents I interviewed in Kano and Maiduguri neighbourhoods corroborated that Boko Haram had used such letters locally, mostly where and when attacks were impending. As can be deduced from the translated version of this letter in Hausa, several complex layers intertwine and require dissection in order to understand the motivations behind certain attacks, instead of resorting to unfounded claims and conspiracy theories which dominate the field of study on the sect. This particular letter, for instance, has no appended signature to prove the identity of its composer(s). This omission can be interpreted in a number of ways. It could be argued that opportunists made it, attempting to instrumentalise the Boko Haram name to achieve some personal objectives. Another interpretation could highlight the then-existing relationship of “trust” between Boko Haram fighters and local communities, since at the time both were enmeshed to some degree. This could explain why some locals believed that Boko Haram was responsible for the delivery of the letter.

Unfortunately, such documents have proven very difficult to access. Individuals were both reluctant to talk about Boko Haram beyond generic responses and to present tangible materials—such as letters, pamphlets, audio-visual cassettes, books, etc.—produced by the sect. Some explained that after 2009 the security forces began arresting anyone found to be in possession of Boko Haram-related materials. Consequently, many discarded theirs or hid them away. This counter-propaganda strategy by the Nigerian security forces has, to a large extent, contributed to the lack of empirical sources that could be used for a more nuanced understanding of Boko Haram, its functioning and its belief system. The security forces’ policy of arresting those found in possession of the sect’s materials forced people to either destroy or hide them from public view. Not only has this made it difficult for scholars to easily access these materials, but it also set in motion what could be described as a further gradual erosion of data on the Boko Haram sect.

Affiliating with Boko Haram: interviews with former members

As it mostly remained impossible to gather information from Boko Haram sympathizers, I resorted to interviewing people who had or claimed to have been affiliated to the sect in the past, but had later distanced themselves. Later in 2014, during my time in Borno, I was, for example, able to interview different young men who hailed from the Shehuri axis within Maiduguri and claimed to have been involved with Boko Haram at several points in their lives. One particular interview was pertinent to my hypothesis that the fear of Boko Haram was a deterrent to speaking about the sect. B.S., my interviewee, explained to me how he was recruited by Boko Haram members who knew him from the neighbourhood when he was around the age of thirteen. B.S. claimed to have been induced into joining the sect due to the monetary incentives they had offered to him, at the time. Although he refused to confide in me as to the breadth of his involvement during his time as a member and if he joined in in acts of violence, he did explain to me that he operated primarily as a “spotter” for higher-ups who he reported to. His higher-ups, according to him, would give him a list of names of people, periodically, and his task was to follow them around without being seen, with the objective to find out the addresses of these potential targets and their daily schedules and then report back. He opined that due to his youthfulness, he was able to operate efficiently because his movements never aroused suspicion.22

Moreover, I gathered some ethnographic data from interviews with officers and participants in the deradicalisation programme set up to rehabilitate Boko Haram imprisoned in Maiduguri and Abuja. In December 2015 I met with one of the project’s workers, Malam Baba Kura,23 who provided me with some insight into the framework of the programme before I made a trip to Abuja to interview some of the enlisted convicts. Baba Kura explained to me that, in December 2015, there were between 30 to 40 Boko Haram members enrolled on a European Union-funded deradicalisation programme in Kuje Minimum Security Prison in Abuja. He told me that the enlisted were those who had signed up voluntarily, as registration was not compulsory. Asked how he was able to have members of the sect sign up to the programme, he explained that he began by reaching out to the “leaders” of Boko Haram within the prison. He was able to gradually convince them of the textual errors in their application and interpretation of Islamic scriptures, after time and effort. Once the high-ranking Boko Haram members joined the programme, they were able, in turn, to go and convince other sect members loyal to them to get on board the programme and give it a try. This example reveals the strong influence the leaders and those who occupy the top echelon of Boko Haram have over the sect’s foot soldiers.

According to Baba Kura, the efforts of the deradicalisation team began to show some success when the Boko Haram prisoners, who had always previously kept to themselves, gradually involved in different activities with other prisoners. An example, cited by Baba Kura, was the participation of some members in football games. This is noteworthy due to the strict stance held by the sect’s ideologues about football (and other sporting activities), which they argue are idolatrous and consequently Islamically forbidden, that is to say, haram.

While I was at Kuje Minimum Security Prison, I also met and interviewed other workers of the deradicalisation programme employed to engage daily with the Boko Haram members. I was told that, at that point, the programme had been placed “on hold” by the Nigerian government, although the rationale behind this was not clear to them. According to the workers interviewed (both men and women), their tasks were compartmentalized, that is to say that specific roles and activities were assigned to them. For instance, there were two Islamic clerics who attended to the religious needs of the participants. The female workers on the team, I was told, mostly engaged in social work with the participants, which I understood to range from engaging with the families of the imprisoned male members (there are also imprisoned female members or female relatives of Boko Haram members) to teaching them technical skills, such as tailoring.

Some observations I made during the course of my prison interviews made me question the efficacy of the deradicalisation programme, wondering if it could bring actual result or if prisoners simply took advantage of it. Indeed, its participants had better living conditions than other inmates, due to the EU direct funding of the programme. I observed that some of the prisoners were also allowed more freedom of movement within the prison than others. For example, I mistook for a prison staff one of the higher-ranking members of Boko Haram participating in the programme because he had been moving around unlike most prisoners, was dressed immaculately, and interacted freely with the other prison staff. I was caught unaware when he was subsequently introduced to me as a prisoner and self-admitted Boko Haram member. This added to the fact that those enrolled on the deradicalisation programme were receiving material incentive. Some of those I interviewed specifically asked me to beg the government for the continuation of the deradicalisation programme, as they benefitted from a better quality of life if compared with “ordinary” prisoners. This differential treatment, I was told, had created divisions within the prison, especially as other prisoners felt that the Boko Haram convicts were worse offenders than they were.

The discovery I made from one of the prison interviews I conducted, I would argue, underscores the importance of giving primacy to the anthropological facet of data production—as there are still several developing layers to the narrative(s) of Boko Haram’s insurgency. The particular prisoner was among one of the assumed Boko Haram members and had been convicted of complicity in the sect’s acts of violence. During the course of our interview, the prisoner spoke in English and told me his name, which did not sound like a Muslim or typical northern Nigerian name. This piqued my curiosity and so I enquired further. The interviewee then divulged that he was a Christian hailing from Benue State and who had previously been employed as a policeman in Gombe State. He was arrested after it was discovered he had been selling weapons to Boko Haram fighters, and then was tagged as a member of the sect.24 This unusual case demonstrates the complexity of the narrative around the Boko Haram insurgency and the difficulty in pigeon-holing the different actors involved in it into neatly-defined analytical categories.

Conclusion

Ethical considerations are an integral part of all empirical research. When inserted within a context in which violence is part of data collection, the need for upholding particular standards becomes even more pressing. As Goodhand posits, ethical decision-making is inherently context-specific, due to the fact that, according to him, it addresses “profoundly political questions, about power, information and accountability.” The American Anthropological Association (AAA) also points out, as part of its guidance stipulations, the necessity of giving a considerate amount of thought to the possible ways in which one’s research might cause harm, as a prelude to the beginning of any anthropological study (Fluehr-Lobban 1991, 26).

An important factor that I had to consider in depth was the “ethical merit” of my study. As Kilshaw mentioned, in her caution to researchers about proper representation of their work, there is always the tendency for those who choose to participate in a study to “hear what they want to hear” (Kilshaw 2013, 126–27), reflexively wanting their viewpoints to be given preference within the grand narrative of the study. With the knowledge of how they are currently perceived in both the local and international media, I concluded that the Boko Haram members I planned on interviewing could not reasonably expect me to express or promise support for their worldview or opinions in exchange for their permission to be interviewed. As such, I let them know that I was only a student interested in hearing their “side of the story” to counterbalance various views and unfounded theories being propagated about the sect. This incentivised some sect members imprisoned at Prison B to allow me interview them, while most of the other prisoners refused my request.

Also, in the process of re-reading through my fieldnotes for the purpose of my academic writing, I have exercised my prerogative to decide to redact certain interviews or parts of them which I felt had the potential to offend humane sensibilities. Philippe Bourgois’s writings on the agency of writing is instructive in this regard. As an anthropologist researching the Salvadorian civil war, the metric on which Bourgois based the self-censoring of interviews he conducted was his fear of his work being used to further the repression of Salvadorians (Bourgois 1990, 48). For me, I did not want to be a contributor towards the fostering of negative ideas, and so, for instance, I decided not to make use of the views expressed by an interviewee, a confidante of the late Mohammed Yusuf and acquaintance of Abubakar Shekau who I met in November of 2013. This was because in the course of our session, he expressed sympathetic views about the massacre of more than forty school pupils at a government secondary school in the Mamudo district of Yobe in July 2013,25 which I considered to have been based on prevalent conspiracy theories and to also have been insensitive to the deceased and their close relatives.

The escalation of violence in northern Nigeria perpetrated by Boko Haram since 2009 has rendered the region an unsafe location for researchers to conduct ethnographic fieldwork as it is impossible for them to decipher the patterns which dictate the frequency or location choices for the launching of attacks. As a response to this situation, a significant amount of research has been undertaken without physical immersion in the field itself, resulting in the production of theoretically and statistically-rich scholarship on Boko Haram. Much of this literature has helped to lay the foundation for nuanced analyses of the nebulous dimensions of Boko Haram within and beyond Nigeria’s borders. As such, conducting fieldwork within a zone where researchers could be affected by violence or put themselves at risk of being arrested, or even worse, should not be considered to be a rigid rule or barometer for measuring the value of academic contributions to the literature on Boko Haram.

However, as this article has attempted to explain, the burgeoning field of study on Boko Haram, regardless of the different disciplinary approaches adopted, requires the injection of new and unrecycled data into the literature in order to advance a more updated, nuanced and complex understanding on the sect. A large part of the scholarship already produced in relation to the Boko Haram insurgency has been predicated on the same limited studies. However, new studies that are historically informed and anthropologically grounded are needed to produce fresh and truly empirical data, renew the perspective as well as explore recent changes.26 With the lack of access to Boko Haram camps within the hinterlands of north-eastern Nigeria for non-members of the sect, a step towards filling the many knowledge gaps about the sect would be the decriminalisation by the Nigerian security forces of the possession of literature—from tracts to letters to written statements and books— and of recordings and videos produced by Boko Haram. Also, making revelatory reports, such as the Galtimari report27 (Galtimari 2011), accessible to researchers and the general public might prove effective in helping sources-reliant research on Boko Haram in the intervening period, until the sect’s violence in northern Nigeria subsides significantly. Only first-hand data collection, I argue, can help move away from oft too rigid categories and instead access the variety and sometimes blurred nature of real-life situations, specifically in Nigeria’s north-eastern region.