General information

Editors

Anita Afonu (Roaming Akuba Films), Jennifer Blaylock (Oberlin College), and Dan Hodgkinson (University of Oxford).

Schedule for authors

- 15 February 2023: Submission of the abstracts

- 1 March 2023: Selection of the abstracts announced to the authors

- 1 June 2023: Papers to be submitted to the journal

- 1 October 2023: Revisions to paper in response to reviews

- 1 December 2023: Final papers to the production and preparation of the materials to be deposited in an open access depositary

- 2024: Publication of the Special Issue

Submission of proposals

To be considered, please submit a 250 to 400 word abstract as well as a short author(s) biography in a single document (DOCX, DOC, or ODT format) including your email address(es) to:

jenniferblaylock@berkeley.edu,

dan.hodgkinson@qeh.ox.ac.uk,

alutaanita@gmail.com,

sources@services.cnrs.fr.

The abstract may be submitted in English, French or Portuguese.

Please use “CFP: Sources / African Revolutionary film” as the subject of your email. In your abstract, please be explicit about which sources you are drawing on and which you plan to publish along with your piece.

The paper should be on average 45,000 signs (including the bibliography, the abstract and the keywords), but shorter or longer texts may also be accepted.

Please consult the requirements for text selection and publication: https://www.sources-journal.org/383, and the guidelines for authors: https://www.sources-journal.org/382.

Presentation

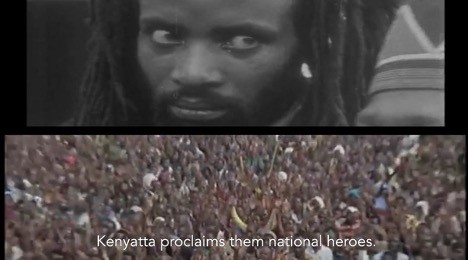

A Glossary of Words My Mother Never Taught Me (Renée Akiteleek Mboya, 2021)

We are delighted to announce this call for papers in collaboration with Sources for a special issue on revolutionary African films made during decolonization, their role in shaping the social lives of African viewers both then and now, and their perilous and complex position as archival sources. Over the last century, politics across the world have been remade through the visual technology of screens. From early Soviet cinema trains and ‘agit steamers’ to YouTube and other ‘streamers’ today, revolutionaries have believed that the moving image, as an easily reproducible and mobile medium of dramatic narratives, offers a powerful way of uniting diverse groups of people under new political visions. The emancipatory projects of decolonization in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, though typically eclipsed in cinema studies and film history scholarship, were a key site in the development of revolutionary screen cultures. The complex, contested legacies of this era of filmmaking often disappeared from public view following the demise of these political projects, the rise of neocolonialism, and the institutional neglect of Africa’s celluloid film industries and their archives during structural adjustment. The specters and memories of this past are becoming increasingly important today, particularly to a new generation of African artists, filmmakers and archivists who are reckoning with history in their own emancipatory projects and in doing so creatively re-imagining what the film archive is and what it can be.

This special issue seeks to gather scholarship on African revolutionary filmmaking and African film and media archives from across academic disciplines and intellectual contexts. We use the term ‘revolutionary’ broadly here to denote the radical, multifaceted projects of transforming society, culture and discourses from colonial rule in ways that both genuinely sought emancipation through the ‘disruption of existing categories’ as well as those projects that embedded authoritarian politics under the sign of revolution (Zeleke & Davari 2022). We welcome contributions from anthropologists, archivists, cinema scholars, filmmakers, and historians (to name a few) to explore the intellectual, political and methodological issues in African revolutionary film histories past and present. This interdisciplinary exchange is, as Roland Barthes argued in 1968, ‘not a question of making disciplines communicate, it is a question of changing them’ (2002 [1968], 58). As such, contributors are strongly encouraged to step back and take an innovative, self-critical, and perhaps experimental approach to academic publication, which involves addressing the politics surrounding the archival sources that they use and, where appropriate, to make available those sources alongside their articles. Where there are no rights issues, embedding film or screen shots within text is not only possible, but encouraged. Other sources that may be included for publication and analysis for example may be particular scratches on a film's surface, or an interview from outtakes, to a copy of a state censorship report. At the center of this call for papers is an interrogation of where and how knowledge is produced. What materials count as sources for understanding African histories? And how does the preservation (or neglect) of African film archives shape political histories today? In line with Sources mission to provide a platform to share sources and research materials, we also see this special issue as a tentative exercise of archive-making.

In addition to centering our sources within the special issue, we specifically encourage submissions on three interrelated themes:

The significance of filmmaking from the 1950s to the 1970s

This special issue explores a range of case studies from the African continent, where new screen cultures and emancipatory political visions co-produced and inspired one another against colonial orders and degrading forms of personhood (Diawara 1992; Gray 2020; Gordon 2002). By 1964, Gamal Abdel Nasser’s regime was building a cinema a week in Egypt. In Ghana, at independence Kwame Nkrumah set about building Anglophone Africa’s most extensive film production facilities and in 1965 founded the country’s first TV station (twelve years before TV was set up in South Africa.) We aim to explore the co-constitution of political visions of independence and African film practices that go beyond reductive discussions of ‘propaganda’ and take seriously the revolutionary agendas of post-independence African filmmakers and states.

Specifically, we seek papers that address the aims, techniques and aesthetics, transnational and international networks, and direct effects of this era of filmmaking, which seemed undergirded by the belief that screens and the dramatic visions of life that they depicted—whether in news reels or feature films—could fire their audience’s imaginations about what political change and moral behavior should look like and recalibrate their audiences emotional indexes in response to these emancipatory visions. As such, we are concerned with the following questions: What were the particular social and political roles that politicians, grass-roots organizers, filmmakers, and industry-professionals imagined media to have in projects of decolonization and national independence? How and why did filmmakers bring together local and transnational ideas and practices in making media and cinematic composition? How were their films and themselves located within wider cartographies of struggles and solidarities, including Cold War dynamics and revolutionary internationalism? What were the social and political effects of these films on audiences, political imaginations and cinematic genres? How were they circulated, written about, watched, debated or censored? How were they framed by, and inserted within, various apparatuses, political, intellectual, artistic, shaping their reception among local and foreign audiences?

The legacies of this era of filmmaking

The independence era’s filmmaking and projects of social transformation cast ‘lingering shadows’ over the discourses of African cinema, as Aboubakar Sanogo (2015, 116) reminds us, as well as the broader contours along which post-colonial political life was imagined, debated and contested for subsequent generations. Sara Salem (2020, 257) argues that in Egypt, Nasser’s independence-era political project ‘set the standard of what a successful hegemonic project looks like, [and] thereby explicitly and implicitly set expectations around what other projects should say, do, or be.’ This special issue is interested in tracing these histories by unpacking the effect of these projects on the lives of people that produced them and on the audiences who watched them, as well as the afterlives of the films themselves—where they went, how they were watched and the effects that they had, including on political and social mobilisation. We are also interested in the following questions: In what ways does this era of filmmaking exercise a power over present-day political imaginations, cinematic genres and present-day social lives? How can and should we study the present-day meanings of this past era, and what sort of sources do we need for these investigations? What role can filmmaking play as a historical practice in this research? What sorts of epistemological effects might these methodological concerns have?

The (re)creation of African film archives

Arguably the most profound public history about this era today is being produced by African artists and filmmakers.1 Renée Akiteleek Mboya’s essay film, A Glossary of Words My Mother Never Taught Me (2021), is an unsettling investigation into her past as a Kenyan that critically repurposes official histories of independence and the gratuitous, neo-colonial ‘shockumentary,’ Africa Addio (Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi, 1966). Mboya’s critical use of the film as ‘a process of archive-making’ to reckon with the past also reveals a stark truth: the relative lack of accessible film sources that can be used to investigate foundational moments in the continent’s past (Fouéré 2016, 84). The combination of a global film industry centered on the Global North and African institutional film archives that have often suffered significant neglect has caused scholars such as Sanongo to suggest that ‘Our film history is a diaspora’ (Cosgrove 2019). In the face of this, a number of archivists, cinema scholars and historians are engaged in costly and complex projects to restore, digitize and restitute this era’s film reels. Other initiatives, such as the ‘Reframing Africa project’ led by Cynthia Kros, Pervaiz Khan, Aboubakar Sanogo and Reece Auguiste at Witswatersrand University, ensure continued circulation of the films and support of African filmmakers (see Kros, Auguiste & Khan 2022). These circumstances pose a set of important, timely questions, such as: What is or can be the African film archive? What are the challenges facing African institutional film archives today? How might increased access to African revolutionary film shape public perceptions on the continent and abroad of African decolonisation? How can and should scholars research lost or neglected film archives? What are scholars’ ethical obligations to archival institutions and existing and new processes of restoration and digitization?