Data associated with this article: James Barnor Archive.

Approx. 30,000 negatives and 4,000 contact sheets, deposited at the Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière (Paris, France).

The archive has been entirely catalogued, and legends added, in the presence of James Barnor for about three quarters of them, and digitalised. The digital database of the archive is not available online at present. It is intended to be made available for exhibitions or research projects.

Introduction

Two women pose seated, smiling, one with her arm around the other, dressed in outfits typical of the fashion in Ghana in the seventies—ensembles adapted from the traditional style known as kaba,1 thick-heeled shoes, small patent leather handbags and large sunglasses (fig. 1). On the wall behind them, in the top left hand corner of the photograph, we can see two covers of a magazine with the title Drum.2 We are somewhere around 1972 in Accra, the capital of Ghana. If this picture catches our attention, it is because it concentrates two logical principles which are the subject of the present article. On one hand, it highlights the effect of triangulation between the subjects of the photograph—people of the female gender—, its creator—a man of about forty at the time—and finally a visual model—magazine covers—which dictate a set of codes of African femininity in those early 1970s. The co-presence of the normative aspect and its direct application by the portrait produced places this image at the heart of our study. On the other hand, this image raises the issue of the circulation of visual models. The Pan-African scale of the magazine Drum, with regard to both the production sites and the areas where it is read, raises questions concerning the fabrication of these models of femininity and their circulation via illustrated magazines.

Figure 1. James Barnor, Untitled [portrait of two friends in front of covers of Drum], Accra, c. 1972

Digitalised and positivised colour negative, 6 x 6 cm.

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

Like this one, James Barnor’s photographs offer the means to apprehend the codification of representations of women by photographic portraits. Born in 1929 at Accra, James Barnor was initially a portrait photographer in a neighbourhood studio from the late 1940s to 1959, while learning the craft of photo journalism during the decade that saw Ghana win its independence on the 6th of March 1957. In 1959, he went to England to perfect his skills as a photographer. The English years (1959–1969) gave Barnor a fertile environment giving rise to a proliferation of practices which shaped his vision as if in sedimentary layers.3 It was in particular for the pages of Drum that Barnor schooled his eye to the standards of fashion photography in around 1965–1967.

This monthly magazine founded in South Africa in 1951 spread rapidly throughout the continent through national editions. Through its content, focused on individual life stories, its lively narrative style,4 its broad spectrum of distribution, the magazine became one of the mainstays of the Pan-African ideology and endeavoured to create a common imaginary throughout the African continent. Like other illustrated magazines launched at the turn of the 1950s in Africa, such as Zonk! in South Africa or Bingo in Senegal,5 it served as a showcase for the idea of an African modernity thought up in Africa. James Barnor worked with the magazine from 1952, thanks to his links with the owner James Bailey, but we shall focus here on his second period of working with Drum and the way this shaped his later photographic practice. Whereas in the 1950s, he mainly covered political news for Drum with photographs that are today conserved in the magazine’s archives in Johannesburg,6 his work was significantly refocused in the 1960s towards portraits of young women from the black diaspora—both African and Caribbean—destined to provide material for a section that became an institution in the late 1960s: Drum’s “Girls of the Month.” This section consisted of a report in one or two pages with pictures and text which showcased the supposedly “real” life of a young woman presented as a model of modernity for a whole readership on the African continent and in the diaspora.7

While it was not the only component of his vision, the imprint of Drum was manifest in the photographs that Barnor produced on his return to Ghana in 1970. There then started a period of broad diversification of his professional activities, under the pressure of the economic recession that hit the country at that time.8 The normative aspect of fashion photography and its male gaze9 is distilled in the wide range of genres that he worked in, from wedding photos to advertising commissions for major corporations. While documenting the social realities of the capital, his photographs became the melting pot of a kind of visual cosmopolitanism10 which today conditions Barnor’s success on the European art market,11 usually to the detriment of an in-depth analysis of the social scope of his photographs and in particular of the relations of gender-based domination that underlie them. In contrast to this decontextualised reception, the present article juxtaposes visual history and gender history to attempt to understand how the photographer has assimilated throughout his career the shifting codes of female glamour reinvented for Africa, codes which reflect a gender-based visual, media, cultural and social order. While there have been numerous studies dealing with this codification, we here propose to tackle the issue on the basis of the archives of a photographer whose professional career and personal life were in phase with the shifts in these norms between the 1950s and the 1980s. In his work, James Barnor is thus both the recipient and the instigator of an ideal vision of “the” African woman. This article thus proposes to relate by an intersectional approach the issue of gender norms and racial bias in the construction of these figures during the post-independence period.

The first part focuses on Drum’s editorial strategy since its launch in South Africa, and in the course of its deployment in West Africa (“The launch of Drum: a visual school out to conquer Africa”)—as a basis for exploring the way the young Barnor took inspiration from the magazine for his studio portraits of women in the 1950s (Part two: “The glamorisation of the studio portrait [1950s]”). The ten years spent in England then provide a basis for thinking about how his contribution to Drum fuelled an ideal of the African woman in the context of the diaspora (Part three: “Ordinary icons: female ideals in the African diaspora press [1960s]”). Finally, in the 1970s, Barnor’s return to Ghana provides evidence of the re-use of these codes inherited from fashion photography but also the influence of African-American models to produce social documentary (Part four: “Social documentary through the prism of the fashion photographer [1970s]”).

Sources and methodology

This article is part of a broader research project based on the exploration of the archives of James Barnor, deposited at his initiative at the Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière (in the fourth arrondissement of Paris) in several sets, from 2016 to 2022. This archive consists of a collection of about 30,000 negatives as well as more than 4,000 contact sheets,12 catalogued and digitalised under the supervision of the photographer. There are also several hundred contemporary prints and a collection of documents (personal correspondence, work contracts, course notes, etc.) enabling an in-depth exploration of his conditions of production in the different phases of his career. The gallery makes use of this archive for commercial purposes, but has also constructed a digital archive base to make it available to researchers, for exhibitions or for research projects. Since the outset of my research in 2018, I have had close relations with this gallery, and have benefitted from unlimited access to the archive, in exchange for my participation in the development of the digital archive base. This platform, at present private, centralises the whole set of negatives and prints making up the archive, structured by a chronological and thematic nomenclature which enables the user to navigate easily among the flood of images. The information delivered by the photographer concerning the contact sheets (the basic unit of this archive) is transcribed there.

A small part of Barnor’s archive is also conserved by the London establishment ABP Autograph, some hundred contemporary negative and prints,13 but because of the size and the accessibility of the archive managed by the Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, I have based my research in this gallery. It should be noted that photographs from the period and modern prints made by the photographer have also been acquired by art galleries such as Tate Britain (2012), the Musée du Quai Branly (2016) and more recently the Centre Pompidou (2021).

Other sources are studied alongside these archives, in particular several editions of the magazine Drum. Because they were available in France, I first consulted all the numbers of the Ghana edition from January 1964 to April 1966, then those of the Nigeria edition from 1966 to 1970, available at the library of Sciences Po Bordeaux. I consulted them focusing on those in which James Barnor had published photographs (that is in five numbers from 1966 and 1967). He also published in numbers which cannot be consulted in France but for which low definition reproductions were transferred to me by the Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière: the numbers from May 1967 and March 1968 conserved at the African Studies Center of the University of Leiden (Netherlands). I also consulted the collection at the library La Contemporaine at the University of Nanterre (January, March and April 1962 of the Ghana edition, then March, May and June 1964 of the Nigeria edition), in which there are no photographs by Barnor but which enabled me to become more familiar with the editorial content of the magazine. More recently, I was able to consult the numbers from 1951 to 1960 available at the Bodleian Library in Oxford—mainly the South Africa edition, and more rarely the East Africa edition for the end of the decade.

While focusing this search on discovering images published by Barnor, my attention was also more broadly fixed on the issues of codification of gender roles, in particular those attributed to or expected of women. To that end, several parameters and contents were observed, whether the role of the image in the representation of the bodies and the roles of women, the visual economy of advertising transcribing these representations, the interactions between the text and the image in the storytelling of the section “Drum’s Girls of the Month,” the contributions of women writers such as the fashion section, with occasional contributions from the Ghanean author Beryl Karikari,14 or the very popular “lonely hearts” mail—the “Dear Dolly” section which appeared from 1951.15 In the earliest editions, between 1951 and 1960, the injunction to beauty is really ever-present in the magazine. Among many examples, in the June 1952 number, the section “Mr. Drum” was devoted to the quest for the ideal beauty pursued by him throughout the continent. Through his eyes, readers are offered “A Quick Look-round for the Ideal of African Glamour”: ten portraits of young women are accompanied by short texts insisting on the particular charms of each “beauty.” To contextualise the tone of these publications, the contemporary testimonies on the editorial strategy of Drum and its evolution are also deployed in this article.16

Thorough exploration of the Barnor archives shows that his attention was not exclusively focused on women. Like other well-known photographers of his generation (whether we think of the canonical examples of the Malian photographers Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, the Burkinabe Sory Sanlé, or the Nigerian Okhai Ojeikere), he was witness to the changes in the representations of the self as much in women as in men. Nevertheless, here it is the portraits of women that capture our attention sine they were more codified by the circulation of illustrated publications such as Drum, whose business was based in large part on the attractiveness of the portraits of young women displayed on the cover. Cameron Duodu, the editor of the Ghana edition from 1960 to 1965, was very explicit on this issue: “But perhaps best of all, Drum exposed its continent-wide readership to what was regarded as feminine beauty in other parts of Africa” (Duodu 2014).

Barnor’s pictures have been selected for their exemplary nature among the typological categories of this archive and their capacity to provide visual testimony to James Barnor’s personal circulation between several cultural universes. On the basis of a corpus combining images destined for publication and images of a private nature, we seek here to trace from within how the canons of fashion photography permeate the practices of a photographer. From this point of view, the procedure takes inspiration from works which investigate the “hidden face” of published pictures by exploring their political and social context.17 Beyond the glossy surface of the illustrated magazine (Jaji 2014, 111–46), this article seeks to compare the published version of the images with the archives: we shall thus explore the contact sheets from which the published images were taken, reproducing the photographer’s intentions in his composition of the portraits of women, and examining the agency of his models. Finally, the exploration of the archives has been considerably enriched by regular interviews with the photographer18 and with some of his models,19 on the basis of the method of photo-elicitation20 which consists in carrying out an interview based on photos which may (or not) represent the people interviewed.

The launch of Drum: a visual school out to conquer Africa

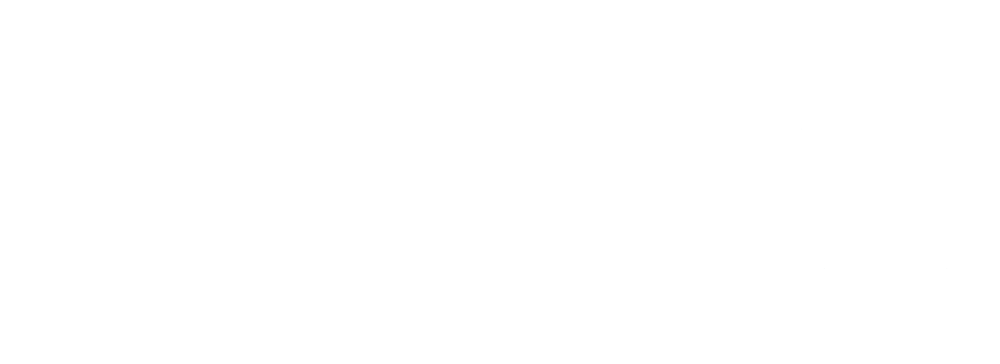

In March 1951 a new illustrated magazine was launched in South Africa, The African Drum, whose sub-heading—“A Magazine of Africa for Africa”—did little to hide the “white hand” (Fleming and Falola 200521) which was at the helm. This first version did indeed continue to propagate the racial and tribal stereotypes regarding the black populations of Africa which it claimed to address. This being so, it met with devastating failure a few months after its launch. The owner, Jim Bailey, hired a new editor, Anthony Sampson, who aimed to “Africanise” the magazine by recruiting black staff. The ebullience of the magazine during these first years—amply commented on (Haney 2010, 106–7; Enwezor 1998; Fleming and Falola 2005)—is incarnated in this emblematic photograph (fig. 2) taken in the Drum offices in 1954 by a young German photographer living in South Africa since 1950, Jürgen Schadeberg. He is known to have trained the South Africa photographers Peter Magubane (1932-), Bob Gosani (1934–1972)—who we see here taking a photo—, and Ernest Cole (1949–1990), figures of a new generation of black photographers whose early careers were intrinsically linked to the success of the magazine (Haney 2010).

Figure 2. Jürgen Schadeberg, “The DRUM Office,” Johannesburg, 1954

Published as an illustration of “Four Years of Drum!,” Drum, March 1955, p. 40–1. Double page: 71 x 54,4 cm.

A photo taken at the same moment and its original legend can be consulted on this page: https://www.baha.co.za/item-detail/?q=19_846 [archive].

© Jürgen Schadeberg. Bodleian Library, Oxford.

The photo attests to the situation of the magazine in the mid-1950s and the deployment of its strategy beyond South Africa. According to the legend that accompanies the version published in the March 1955 number, we can see “squatting on the ground, the circulation manager Benson Dyanti and the accountant Ken Mtetwa [who] were planning the expansion of Drum in Africa” (“Drum—South Africa’s Black Picture Magazine” 1984). In the background, two men are holding a magazine where can be made out the portrait of a white woman in pin-up attire. The legend reads: “Victor Xashimba, dark room assistant, and Dan Chocho, journalist, want to destroy the last number of Africa.” This magazine, designated as the “little sister” of Drum, was another publication launched by Bailey in the early 1950s, but it was a failure. All the white women sexualised in the pages of Africa appear as the counterparts of the young black models shown on the cover of Drum ever since the first editions (Enwezor 1998). These portraits of women are shown in succession on glossy paper every month. Already in the 1950s, when colour photography was virtually non-existent on the African continent, these photographs were manipulated—literally speaking—by an exclusively male team and retouched in the alluring colours that define the canon of the modern African woman. These codes derive from the visual repertoire of the major publications of the western press that Bailey and his white editors knew well (Newbury 2010).

If the dominance of a male gaze is undeniable in the editorial strategy of the magazine, Tstisi Ella Jaji has shown that the glossy surface of similar publications has nevertheless contributed to forging an imaginary community at the scale of the continent. Analysing the first front page of the South African magazine Zonk!, launched a little before Drum, which gave the star role to the actress and singer Dolly Rathebe, she considered that the image of so self-assured a woman “[changed] fundamentally the perception that African women may have had of themselves and of the rest of the world.” (Jaji 2014, 113). She goes on to insist on the pivotal role of the image of women in the codification of an ideal “of domestic life, consumption of the media, urbanisation, modernity and political identity in post-World War Two Africa” (ibid.). Thus the scope of the magazine as a textual space (Johnson 200922) but also a visual space made a major contribution to the spread of gender norms throughout the continent. It provided a set of stylistic prescriptions which defined the gender ideals of an epoch when many countries in Africa, on the threshold of independence, were in quest of new social models. If it is difficult to evaluate the respective male and female share of the readership of Drum, we may nonetheless stress that its eye-catching front pages artfully target both audiences throughout the continent.

Drum rapidly spread to other regions of Africa and exported to them its own aesthetic while adapting to the culture of the countries concerned. From the end of 1951, Bailey and Sampson tried to develop its network, notably in Ghana and Nigeria, but the success of the enterprise initially remained rather limited. The West African readership felt rather remote from the themes treated in the columns of the magazine which referred to political, social and cultural realities specific to South Africa, as James Barnor, who began to work with Bailey in 1952, testified: “When I was working for Drum in Ghana, we didn’t have any trouble at all. We didn’t even know what was going on” (Manu et al. 2021). To compensate for this effect of distance, a process of adaptation began to develop at this time: initially, only a few items, then gradually a substantial part of each number were dedicated to portraits or news items specific to these countries, up until the launch of a West Africa edition in 1956 (Priebe 1978). In 1957, two permanent offices were set up in Accra and Lagos, and in 1960 Drum put into operation the split long expected by the readership of the two countries, offering two distinct editions for Nigeria and Ghana. The golden age of the magazine is generally placed in the early 1960s, reaching, respectively, 90,000 and 65,000 readers each month. In these two versions, pictures occupied considerably more space than in the South Africa edition, which devoted a major part to written texts, considered initially as the primary vector of identification for the readers. In Ghana, the importance of new models of identification in the illustrated press was perhaps all the more marked given that the deployment of Drum coincided exactly with the period of negotiations for independence led by Kwame Nkrumah, from 1951 to 1957.

The glamorisation of the studio portrait (1950s)

Bailey’s strategy for deployment consisted in finding locally authors and photographers capable of providing material for the pages of the magazine for the purpose of “West Africanising” it. This network was deployed throughout the decade, reaching around three hundred agents for the whole of the Nigeria and Ghana teams at the beginning of the 1960s (Toyin and Falola 2005, 148). James Barnor was among them (fig. 3) and remembers the revolution that this kind of press represented in his country:

“In fact, before Drum came, there was no idea of such magazines publishing pictures. So, even though I didn’t work for them full time, I was offered a different level of photography. I had my studio photograhy, I had my journalistic photography, and that extra which makes (sic) Drum a new thing in Africa.” (Manu et al. 2021)

Figure 3. James Barnor, Untitled [Jim Bailey, left, another member of the Ghana team and James Barnor, right], Accra, Ghana, c. 1952

Digitalised and positivised negative, 6 x 6 cm.

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

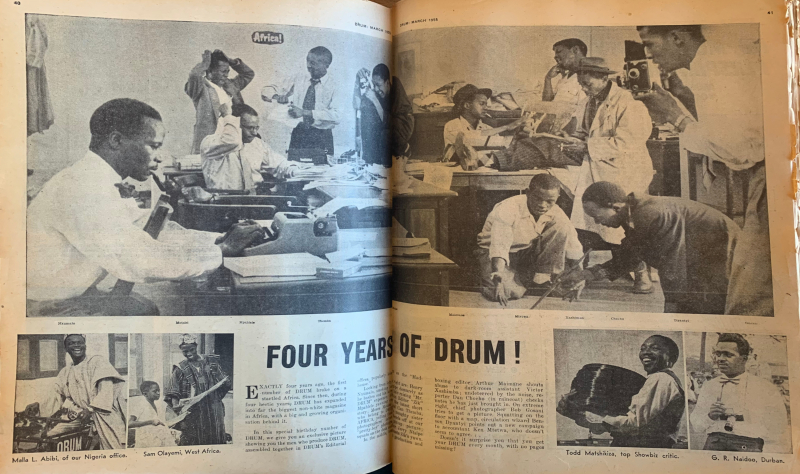

In the numbers from the 1950s that I have been able to consult, very few of the photographs can be attributed with certainty to Barnor. Nevertheless, in August 1952 there is a portrait of his sister Ivy Barnor, used to announce the beauty contest “Mr and Miss Africa.”23 Launched in January 1952, the idea was to adapt the western genre of the beauty contest with the specific aim of “finding the ideal of African womanhood,” and, a few months later, her male counterpart (Cowles 2001) (fig. 4). Photographed by her elder brother, probably on the occasion of a church ceremony, the young Ivy has her hair in an elegant chignon; her face is shown beside a portrait of a young Southern Rhodesian, just as elegant, and a smiling baby—also photographed by Barnor although he was not credited for it24—, as if the three formed the ideal family of this young African generation.

Figure 4. Mr. and Miss Africa 1952 Beauty Contest, featuring Ivy Barnor (right). Drum, international edition, August 1952

Bodleian Library, Oxford.

This example shows that in his studio, baptised “Ever Young,” the photographer was as early as 1951 the vector of the gender norms imposed by the magazine. In 1947, James Barnor started his apprenticeship as a photographer in the studio “Yehowa Aakwe” (“God is watching” in the Gã language) of his cousin, J.P.D. Dodoo. It was photography being ever-present in his family (another of his cousins and a maternal uncle were also photographers) that oriented him towards this profession. During the first years of his career, between 1949 and 1952, a certain conformity in the execution of the portrait reflected not only the technical rigidity imposed by the recourse to the view camera using glass plates25 but also the formal codes passed on by his trainers. But from 1953 on, his installation in his premises in the harbour area of Jamestown, one of the oldest and most lively neighbourhoods in Accra, contributed to the deployment of a less formal aesthetic. This gradual emancipation took inspiration from different sources which reflected the influence of cultural industries in the process of globalisation, notably the cinematographic imagery which was developing rapidly in the major African cities (Behrend 1998). It should be specified here that Barnor’s studio was located very close to the Sea View Hotel, a nightspot founded in 1873 which was also one of the first cinemas in the city (Jackson 2019).

These international influences contributed to the development of a sexualised aesthetic in James Barnor’s studio portraits which increased over the course of the decade. The idealisation of the anonymous women who were eager to pose before the lens of the young photographer was based on the strong distinction in the respective representation of men and women, as is well illustrated by a page of Barnor’s personal album (fig. 5). We can see clearly here that with the women, the skin and the sexual attributes such as the low neckline are much more visible, and the postures more sensual, than with the men, often shown in active positions and in suits.26 The pose of the young woman in the bottom left corner became a classic of the studio and is somewhat reminiscent of the pin-ups on the covers of the magazines of the time—the pose is for example frequent on the cover of Drum or Jet.27 The development of a sexualised aesthetic among young women was however rarely as explicit in this portrait, where the skin and the low neckline of the model are on display, owing to the increasing control of morals exercised by Kwame Nkrumah’s government targeting young people from the mid-1950s on.28 It then rather took the form of what we here refer to as the “glamorisation”29 of the studio portrait, understood as the glossing over of the markers of social status in the individuals represented—women in this case—to showcase their aesthetic or sexualised attributes. An expression of this can be seen in the series of portraits of Miss Accra taken by Barnor in about 1957, which are typical of the photographer’s production in the second half of the 1950s, in particular with regard to the poses and camera angles used (fig. 6). The three-quarter profile predominates from 1955 as one of the signs of the progression of the functions of the studio. The studio no longer served solely to define the social identity of the subjects, to mark the high points of their success in the system of moral values of the country (marriage, access to a profession, etc.), but to show the specifically aesthetic character of the individuals. The choice of outfits of his clients, in particular, is shown as the reflection of a fashion that mingles aspects borrowed from 1950s Western culture—here backed up by the allegorical presence of the Coca-Cola bottle—and wardrobe items tailored from material with local symbolic significance.30

Figure 5. James Barnor, Untitled [Portrait cutting from a page of an album constituted by the photographer], Ever Young studio, Accra, Ghana, c. 1953

Size: 24 x 30 cm.

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

Figure 6. James Barnor, Miss Accra 1957 [?], Ever Young Studio, Accra, Ghana

Digitalised and positivised negative contact print, 6 x 6 cm.

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

Thus, although in the 1950s James Barnor’s work for Drum was not exclusively devoted to fashion photography and portraits of women, his studio production, in particular the portraits of young women, already reflected a familiarity with these conventions, which was to be exploited and enhanced during his stay in England from 1959 to 1969. We can also see in them the hallmark of the visual fashioning operated by Drum, which, while it did not succeed in achieving the status of an African Time or Life, as Bailey had originally planned, was nonetheless the most popular magazine ever distributed in Ghana.

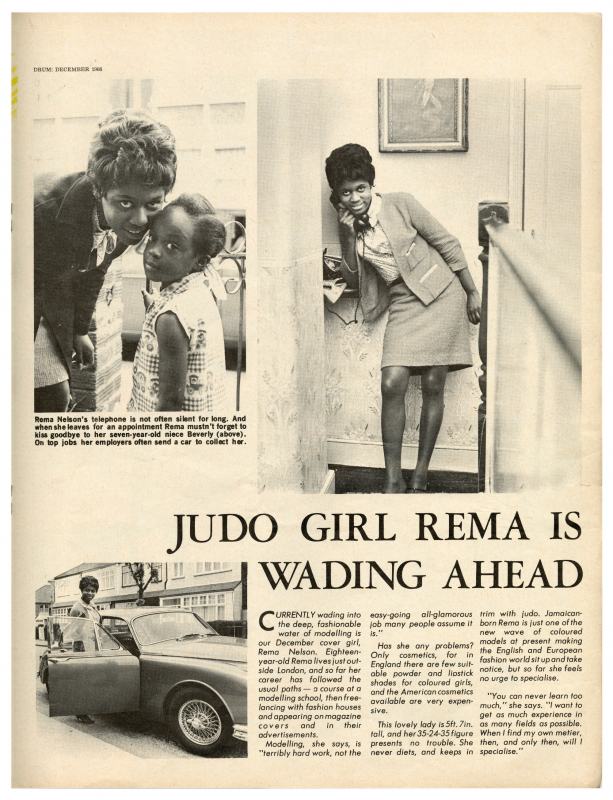

Ordinary icons: ideals of womanhood in the press of the African diaspora (1960s)

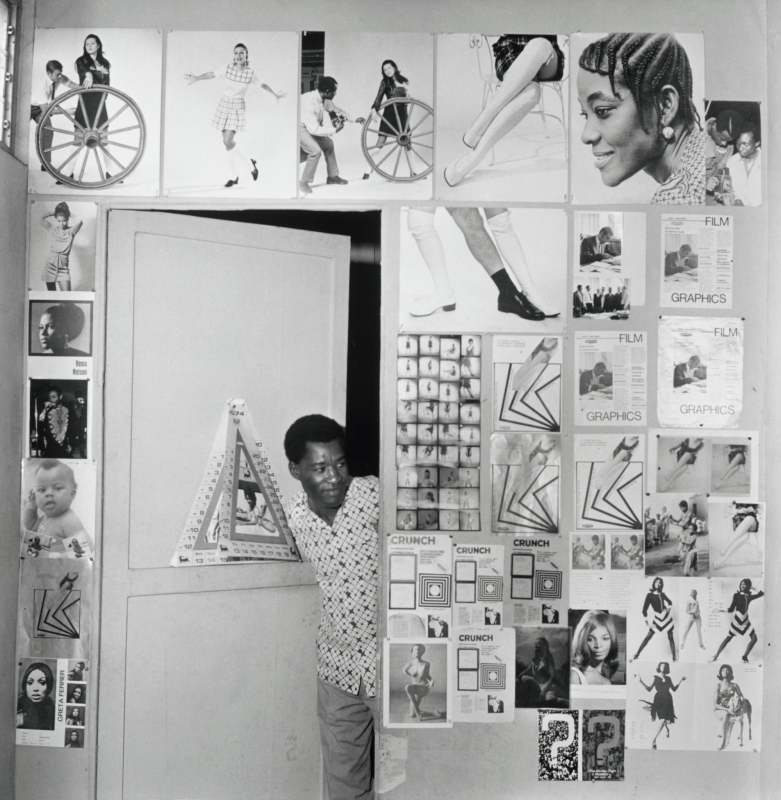

In 1959, James Barnor decided to leave his studio and his family in Accra to go to live in England, wishing to perfect his mastery of the photographic medium and encouraged by his connections with Jim Bailey.31 On his arrival, he trained at the photography department of Kent college of applied arts (Medway College of Art, Rochester) and worked in a photography laboratory specialising in colour printing (Colour Processing Laboratory, based at Edenbridge, also in Kent) from 1960 to 1965 (Mussai 2016; Lavernhe 2021). It was only in the middle of the decade that he rejoined the staff of Drum, which had opened an office in Fleet Street, where at that time most newspaper and magazine offices were located (Oppenheim 2019). Barnor’s training at Medway College enhanced his fashion photography culture. The college encouraged exchanges between the design department, which included the photography course James Barnor was taking, and the fashion and textile department.32 Barnor was therefore regularly called on to photograph the creations of his stylist fellow-students. The different sub-genres of fashion photography (studio portrait, outdoor portrait, close-up focusing on the details of an outfit, etc.) which he worked in is evident in the numerous contact sheets from this period in his archive (fig. 7). One photograph also shows James Barnor posing against a wall of pictures which is evidence of the emphasis on industrial and advertising photography at this college. It was also the expertise in colour photography which he developed during these years that helped him to rejoin the staff of Drum.33 Barnor offered a series of pictures to the magazine, this time pivoting clearly towards portraits of women,34 from September 1966 to December 1967.

Figure 7. James Barnor, Untitled [Model posing for a student assignment], Rochester, Kent, c. 1962

Digitalised and positivised negative, 6 x 6 cm.

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

During the years preceding this collaboration, there was a surge in press publications from the black communities in the United Kingdom (the Black British press) in reaction to the rise of racism the country was then experiencing.35 However, Barnor’s testimony gives a more nuanced view of this observation: “I wanted to do cover photos or fashion photos, like for the ‘normal’ English papers […]. There were few black magazines to begin with” (Manu et al. 2021). His contribution to the numbers of the Nigeria and Ghana editions of Drum thus reflected the paradox of a “re-aestheticisation of blackness” (Ford 2015) through the adoption of the norms of the white press. But the magazine also took inspiration from the major African-American references, Ebony and Jet, which aimed to subvert “the familiar markers of degradation, spectacle, and victimization” of black populations in America, to promote on the contrary an “iconic blackness articulated to […] symbols of class respectability, achievement, and American national identity” (Stange 2001). The project was quite different as regards the pages of Drum: the portraits of young women are in fact enlisted not for the promotion of a national consciousness but at the instigation of models of social success in the very experience of the diaspora.

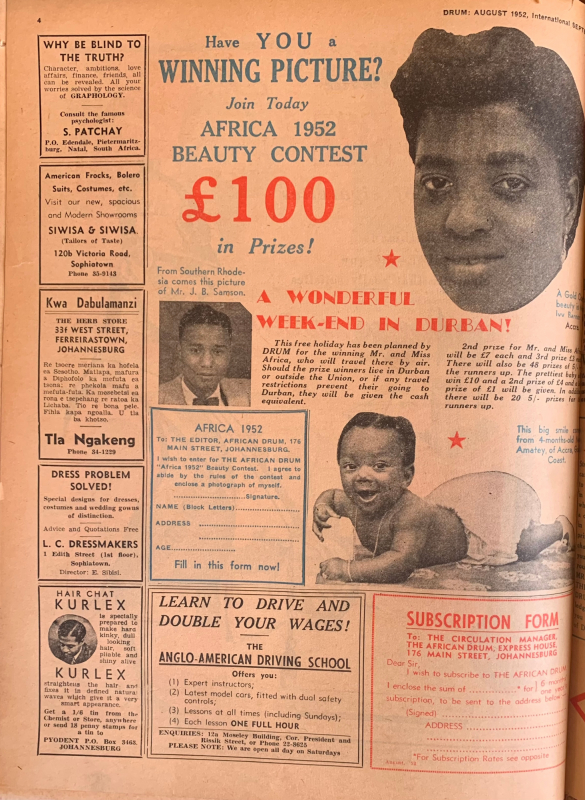

The female ideal of the “girl about town”36 (Johnson 2009), which had made its way in the western metropolis, was usually based on an affirmation of her ease in relationships, her dynamism or her ambition. Barnor’s portraits made the covers the magazine seven times, and at least six times the inside pages for the “Drum’s Girls of the Month” section. Most of the time, his models were not professionals and could be his personal acquaintances,37 but they were transformed into icons through Drum’s visual strategies. Here, it is worth comparing the covers of the magazine, which, to make it more eye-catching, banked on a glamorisation or even a very striking sexualisation of the models, with on the other hand the portraits in the inside pages which were rather based on the scenario of their supposedly “real” lives. On the cover, the close-up is invariably the rule, with more rarely a bust shot. Like that of the black South African icon, Dolly Rathebe, in the early 1950s (Jaji 2014), it is here the gaze of women who are complete strangers which by its directness incites the curiosity of the reader in Africa (fig. 8 et 9). The accent on the details of their beauty treatment, such as the kohl eye makeup and the saturated colour code accentuate their brazen attitude. In the section itself, it is the more sober black-and-white (and less costly to produce) that is used, closer to documentary photography. Thus the young Rema Nelson (fig. 10), an eighteen-year-old Jamaican who was hoping for a career as a model, was photographed in her house in the suburbs of London. The staging of the scene uses the motifs of the telephone and the car, symbol of the “material cultures of success” of the 1950s-1960s (Rowlands 1996; cited in Fouquet 2014, 7). At that time, the visual consumption of fashion magazines had accustomed western readers to an almost natural association between women and cars.38 In the context of institutionalised racism in England in the years 1967–1968 (Gilroy 1987), the car associated with a young black woman evokes a horizon of expectation and consumption of which Drum had become the showcase. Consultation of the contact sheet these portraits were taken from reinforces this observation, since we see in several shots the car given almost as much of a star role in the picture as the young woman. Furthermore, at least three of the sessions organised by James Barnor in about 1966 showcase luxury cars, recycling a motif and a way of posing his models he had experimented with during his course at Medway College of Art (fig. 7). The Jaguar, albeit borrowed by Barnor from an African-American artist friend,39 Bill Hutson, became in a lasting way the instrument of a narrative where the staging of a desire for social success was linked to the model of American consumption.

Figure 8. James Barnor, Untitled [Portrait of Constance Mulondo on the cover of Drum, Nigeria edition, August 1967]

Page size: 37.5 x 27.5 cm.

Library, Sciences Po Bordeaux.

Figure 9. James Barnor, Untitled [Portrait of Helen de Coteau on the cover of Drum, Nigeria edition, December 1967]

Page size: 37.5 x 27.5 cm.

Library, Sciences Po Bordeaux.

Fig. 10. “Judo Girl Rema is Wading Ahead,” Drum (Nigeria edition, December 1960).

Story showing Rema Nelson at home, photographs by James Barnor. Page size: 35.5 x 27.5 cm.

Library, Sciences Po Bordeaux.

Behind the glossy surface of the magazine and the theatrical staging of the lives of these ordinary icons are concealed the visual strategies orchestrated by a spectrum of actors, all male. The testimony of Erlin Ibreck, a young Ugandan student photographed by Barnon on several occasions between 1966 and 1968, has shed light on the conditions of production of these images.40 In particular, she insisted on the generation gap that separated her from Barnor, who was twenty years older than her and who she therefore considered as her “mentor.” Erlin Ibreck also recalled that the amateur models like her were not paid, but that it was considered an honour to be shown on the front page of a magazine with such a wide distribution in Africa. The models could play an active part in the choice of their outfits and accessories. For one of the sessions for the “Drum’s girls” pages, James Barnor took Erlin Ibreck to the home of Bill Hutson, the African-American artist who also lent her his Jaguar41 (fig. 11). She tells how she proposed several outfits to the two men, outfits she had bought at the cheap chain stores of 1960s London.42 Then it was the men who managed the artistic direction, choosing the dress she wore and having her pose in the modernist decor created by Hutson’s works, whose geometrical motifs were artfully reflected in the patterns of the dress and the design of the jewellery. This phenomenological approach to the photographic session also makes it possible to grasp the relations of dominance, but also the agency of the model, which are at play behind the staging of these portraits of women. This narrative dimension, the main trigger of the sexualised aesthetic of the young women he photographed in the 1960s, was to leave its imprint on the art of the portrait as practised by Barnor in the years to come.

Figure 11. James Barnor, photo session for Drum with Erlin Ibreck in the apartment of the African-American artist Bill Hutson, Kilburn, London, 1967

Digital and positivised colour negative, 6 x 6 cm.

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

The social documentary through the prism of the fashion photograph (1970s)

Back in Accra in 1970, James Barnor took on a range of professional functions, all related to his expertise in colour photography,43 or to links he had developed with graphic creation, but he no longer worked for the press strictly speaking. The decade was shaken by coups d’état which destabilised the country’s economy, made photography work precarious and impinged on the freedom of the press. While the business affairs of Ghana Drum were already going badly, the accession to power of General Acheampong in 1972 sounded the death knell of the national edition (Fleming et Falola, 16244). Despite this decline of the illustrated press, the covers of Drum continued to decorate Barnor’s studio (fig. 1). This can be seen in particular in a photo taken in his studio in the mid-1980s which shows, pell-mell, portraits of the “Drum girls” photographed in the 1960s (including Rema Nelson) and other fashion photos showing racially type-cast models whom he did not photograph himself (fig. 12). The imaginary of the commercial studio, always devoted to multiple strategies of invention of the self, going beyond or even subverting the simple attribution of the legitimate roles of the social order,45 thus perpetuates the references to glamour photography.

Figure 12. James Barnor, assistant at Studio X23, leaving the dark room, Accra, Ghana, between 1983 and 1987

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

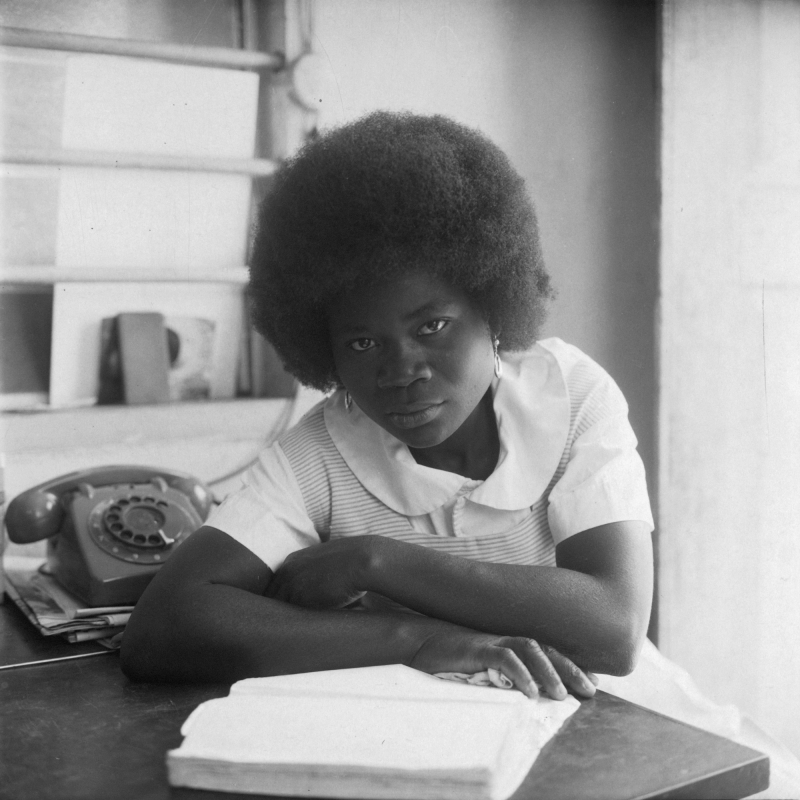

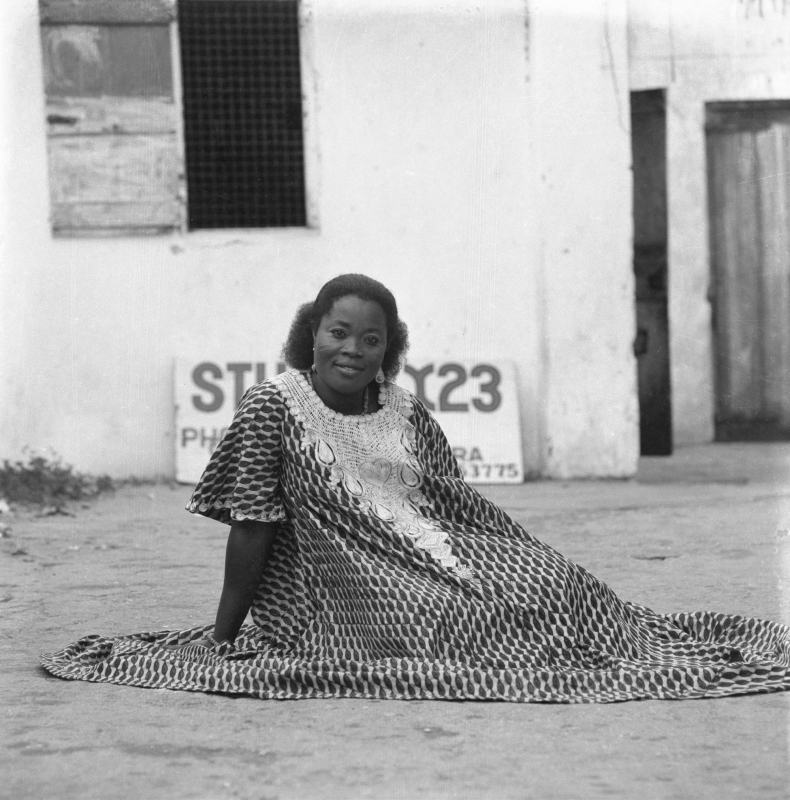

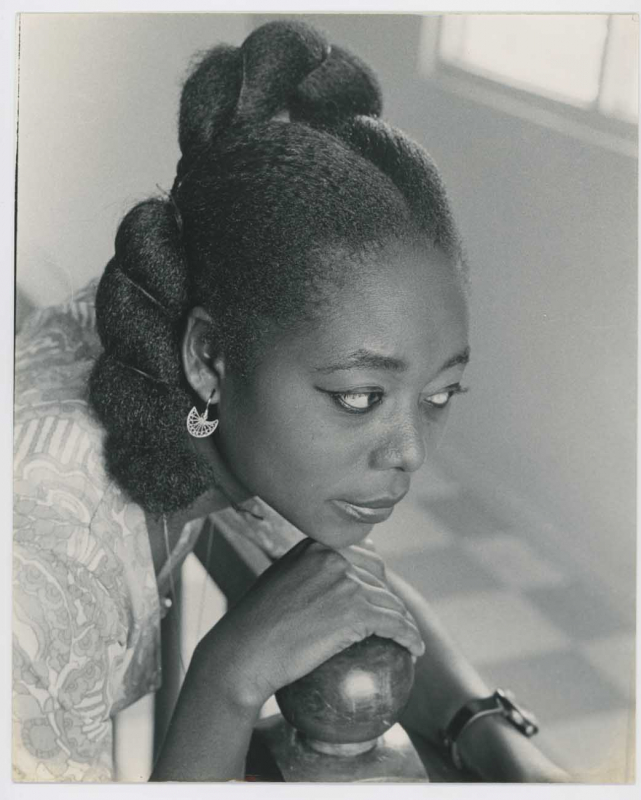

We identify these references to glamour photography first of all at the scale of the studio itself, where the photographer reworks certain of the motifs experimented with in England in the 1960s, such as the telephone or the cars, already seen in the portraits of Rema Nelson for Drum in 1966 (fig. 13). The studio of the 1970s, multifaceted and amendable at will, plays on the combination of interior and exterior spaces. There are also material factors, in this case very small premises, which oblige the photographer to make do with what he’s got. His clients sometimes pose on the ground in his courtyard, in the glamour poses already observed in the 1950s, which contrast with this stark decor (fig. 14). But the fashion photographer’s lens also went outside the studio and acquired a whole corpus of images produced for private use, without any intention of publishing them or commercialising them. We see, for instance, facilitated by the evolution of the photographic medium, the fairly frequent recourse to the close-up, highlighting as for the Drum models beauty features such as hairstyles which became a veritable exercise in style in the 1970s (fig. 15). The hairstyles were commented on as privileged markers of cultural expression sometimes borrowing from the register of African-ness,46 sometimes from that of cosmopolitanism.47 With Barnor, the hairstyles are above all material for photographic experimentation, real sculptural objects which enable him to test his sense of composition. In a portrait taken on the occasion of the diploma award ceremony in a higher education establishment at Accra, he photographed the hairstyle of a student, highlighting the contrasts of its coils by means of a neutral background improvised in the courtyard and an upward-pointing camera angle which accentuates the composition of the picture (fig. 16). Glamorisation is fully at work since we see here a photographer, initially commissioned to cover an official event in a documentary style, go off at a tangent to produce a portrait directly inspired by his experience as a fashion photographer. In the rest of the contact prints related to this event, the full sequence shows the same young woman shaking the hand of one of the directors of this establishment to receive her diploma along with her fellow students.

Figure 13. James Barnor, Cynthia Ankrah, classmate and friend of the photographer’s daughter, Studio X23, 1970s

Digital and positivised negative, 6 x 6 cm.

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

Figure 14. James Barnor, Portrait of a woman, Studio X23, Accra, around 1975

Digital and positivised negative, 6 x 6 cm.

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

Figure 15. James Barnor, Miss Sammy Tetteh, Secretary, at her desk, Accra, Adabraka, 1970s

Period print, 20.5 x 25.5 cm.

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

Figure 16. James Barnor, Untitled [Diploma award ceremony at the Opportunities Industrializations Centre], Accra, 1970s-1980s

Digital and positivised negative, 6 x 6 cm.

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

But the re-use of visual supports experimented for Drum is never more obvious than in a set of full-length portraits taken with an upward-pointing camera angle in which the models display their choice of clothing as a way of belonging to a “soul” aesthetic (Ford 2015). This style, forged in Harlem in the 1960s, spread across the Atlantic through printed materials such as magazines and record sleeves. It may be understood as a visual portrayal of African identities from the United States: it is the idea, materialised in the choice of clothing and hairstyles, of African roots which, “re-aestheticised,” become the springboard for an emancipation of black populations throughout the diaspora. Thus, if in the 1960s the aesthetic deployed in Barnor’s images consisted in a repossession and adaptation of hegemonic white models, in the 1970s it rather borrowed from the repertoire of a globalised black culture. As in certain reports produced for Drum, the public space is made use of as the stage-set for the affirmation of identities that are embedded in a cosmopolitanism lived, staged and displayed from Africa. In this portrait of his niece Naa Ayeley Attoh (fig. 17), the upward camera angle accentuates the motif of her spread-out dress which might equally well be seen as a reference to the psychedelics imported from the United States as to a geometric and repetitive aesthetic typical of African textile art. Reinforcing the stylistic choice of this outfit, the camera angle firmly situates the young woman in the urban space, signified both by the modern building and the signpost in the background.48

Figure 17. James Barnor, Naa Ayeley Attoh, James Barnor’s niece, posing in front of Lutterodt Circle, Accra, around 1974–1975

Modern analog print.

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

We also see the imprint of the culture in more spontaneous contexts reflecting the highpoints of social life at Accra. For example, there are the wedding photos, which are among the most numerous during this epoch. Often taken with the contre-champ from portraits, highly codified, taken on the steps of a church, James Barnor photographed the outfits of the guests to highlight the matching of their dress choices with the fashions of the day, the effort at self-ornamentation by outfits and accessories that belong to a global culture. In a colour portrait of the early 1970s, we can see the very clear evolution of female dress codes in relation to Barnor’s early career, with this fake fur beige beret, the large round glasses à la Janis Joplin, but above all a miniskirt made of sun-coloured material (fig. 18). When this photograph was selected for an exhibition at the Rencontres d’Arles in the summer of 2022,49 Barnor was reticent about it, precisely because he considered it as an outfit that was a bit too daring for the epoch. This puritanism, which may seem anachronistic to us, in fact expresses the concern of a man who did not wish to have attributed to him a posteriori an inappropriate gaze on the members of his community, all the more so as the photograph was taken in the context of a religious ceremony.

Figure 18. James Barnor, A wedding guest in the park behind Holy Trinity Cathedral, Accra, around 1971

© Archives James Barnor/Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière.

If certain pictures are free of any direct reference to their local roots, others re-use the visual vocabulary inherited from Drum to transpose it to the documentation of ceremonies where signs of local or national affiliation are on display. In one of the best known of Barnor’s photographs, we see two women in dresses made of kente, a material that since the mid-1950s had become the symbol both of Ashanti royalty and of the Pan-African struggle (fig. 19) (Fila-Bakabadio 2009). The iconic character of this picture derives from the encounter between a style of representation borrowed from the lexicon of modernity—the colour photograph—and references to the historical culture of Ghana, here symbolised by the sculptural hairstyles of the young women, and by their similarity which borrows from the prized motif of the double in the art of West African statuary (Sprague 1978; Micheli 2008). These visual signs which index African-ness to varying degrees are thus remixed in a modernist aesthetic taken from fashion photography, of which cars and colour are two direct vectors.50 Red on red, highlighted with gold and typographical characters recalling the world of advertising, taken with a slightly upward-pointing camera angle which always denotes the style of the illustrated fashion press: this photograph shows the influence of printed materials in the Accra social worlds. It is this borrowing from a globalised visual culture that explains today the success of images such as this outside their territory of production.

Figure 19. James Barnor, Untitled [Two friends dressed for a church ceremony], around 1972

© James Barnor/Autograph ABP.

Today’s re-readings: glamour to the detriment of social value?

In 2021, as part of the retrospective exhibition dedicated to James Barnor at the Serpentine Gallery in London, there was the launch of the Serpentine Studios, a creative laboratory where several young artists were invited to come together to work on pictures by the photographer. Among their creations, a photo montage by Jaerome Andre superimposed on a fictitious Vogue cover the face of one of the “Drum girls” photographed James Barnor (Helen de Coteau, see fig. 9) and a full-length portrait of the singer Rihanna. Along the same lines, we may cite the cover of Vogue Italia of April 2021 (number 847) which, before the opening of the exhibition, showed the international model Adwoa Aboah, a British woman of Ghanean origin, in front of Piccadilly Circus, mimicking the pose in which James Barnor had in 1967 photographed the Ghanean radio presenter Mike Eghan for Drum (“James Barnor, Adwoa Aboha e Vogue Italia” 2021).

Since James Barnor’s earliest exhibitions in the world of international art a dozen years ago, the attraction for his glamour portraits, crowned by re-employment of this kind, has been constantly on the rise and polarises the attention paid to the photographer. The goal of the present article is to momentarily break free of the context of the current reception of his work to propose a more in-depth reading of the influences of fashion photography in James Barnor’s production. It has offered a basis for exploring the editorial framework in which this glamour perspective was fashioned in the gaze of a young photographer in the years 1950 to 1970, a framework intrinsically linked to the logical precepts of racial and gender domination in and by the visual culture. The major magazines of the white press in this period have the status of hegemonic references, but they are also taken up and subverted by the black magazines. Among them, Drum has left a lasting mark on the practices of James Barnor, progressively becoming a filter over his documentation of the social realities of Accra through a spectrum of genres. From the use of poses and ways of composing the image to this visual universe of globalised fashion, there emerged a laid-back quality in the attitude of the models, a “black cool” aesthetic (Tulloch 2016) which developed transnationally, and from which Barnor borrowed his vocabulary. This hybrid imagery which was the foundation of a transcontinental blackness was mainly fuelled by the circulation of illustrated magazines which reached its peak in the years 1960–1970 in West Africa.

A number of photographers working in the neighbouring countries to Ghana reflected its impact in their portraits, such as Sory Sanlé (1943-) in Burkina Faso who in around 1975 posed two lovers in evening dress in front of an assemblage of pages cut out of fashion magazines and pasted onto the walls of his studio (fig. 20). If the black magazines and the African-American visual culture worked their way into the practices of Ghanean photographers like Barnon, it must be noted on the basis of the Sory Sanlé’s choice of images that white models of the genre continued to be a major reference at the same time in other West African countries.

Figure 20. Sory Sanlé, “Les amoureux timides,” Burkina Faso, 1975

© Sory Sanlé, Courtesy of Tezeta.

![Figure 1. James Barnor, Untitled [portrait of two friends in front of covers of Drum], Accra, c. 1972](docannexe/image/1134/img-1-small800.jpg)

![Figure 3. James Barnor, Untitled [Jim Bailey, left, another member of the Ghana team and James Barnor, right], Accra, Ghana, c. 1952](docannexe/image/1134/img-3-small800.jpg)

![Figure 5. James Barnor, Untitled [Portrait cutting from a page of an album constituted by the photographer], Ever Young studio, Accra, Ghana, c. 1953](docannexe/image/1134/img-5-small800.jpg)

![Figure 6. James Barnor, Miss Accra 1957 [?], Ever Young Studio, Accra, Ghana](docannexe/image/1134/img-6-small800.jpg)

![Figure 7. James Barnor, Untitled [Model posing for a student assignment], Rochester, Kent, c. 1962](docannexe/image/1134/img-7-small800.jpg)

![Figure 8. James Barnor, Untitled [Portrait of Constance Mulondo on the cover of Drum, Nigeria edition, August 1967]](docannexe/image/1134/img-8-small800.jpg)

![Figure 9. James Barnor, Untitled [Portrait of Helen de Coteau on the cover of Drum, Nigeria edition, December 1967]](docannexe/image/1134/img-9-small800.jpg)

![Figure 16. James Barnor, Untitled [Diploma award ceremony at the Opportunities Industrializations Centre], Accra, 1970s-1980s](docannexe/image/1134/img-16-small800.jpg)

![Figure 19. James Barnor, Untitled [Two friends dressed for a church ceremony], around 1972](docannexe/image/1134/img-19-small800.jpg)